|

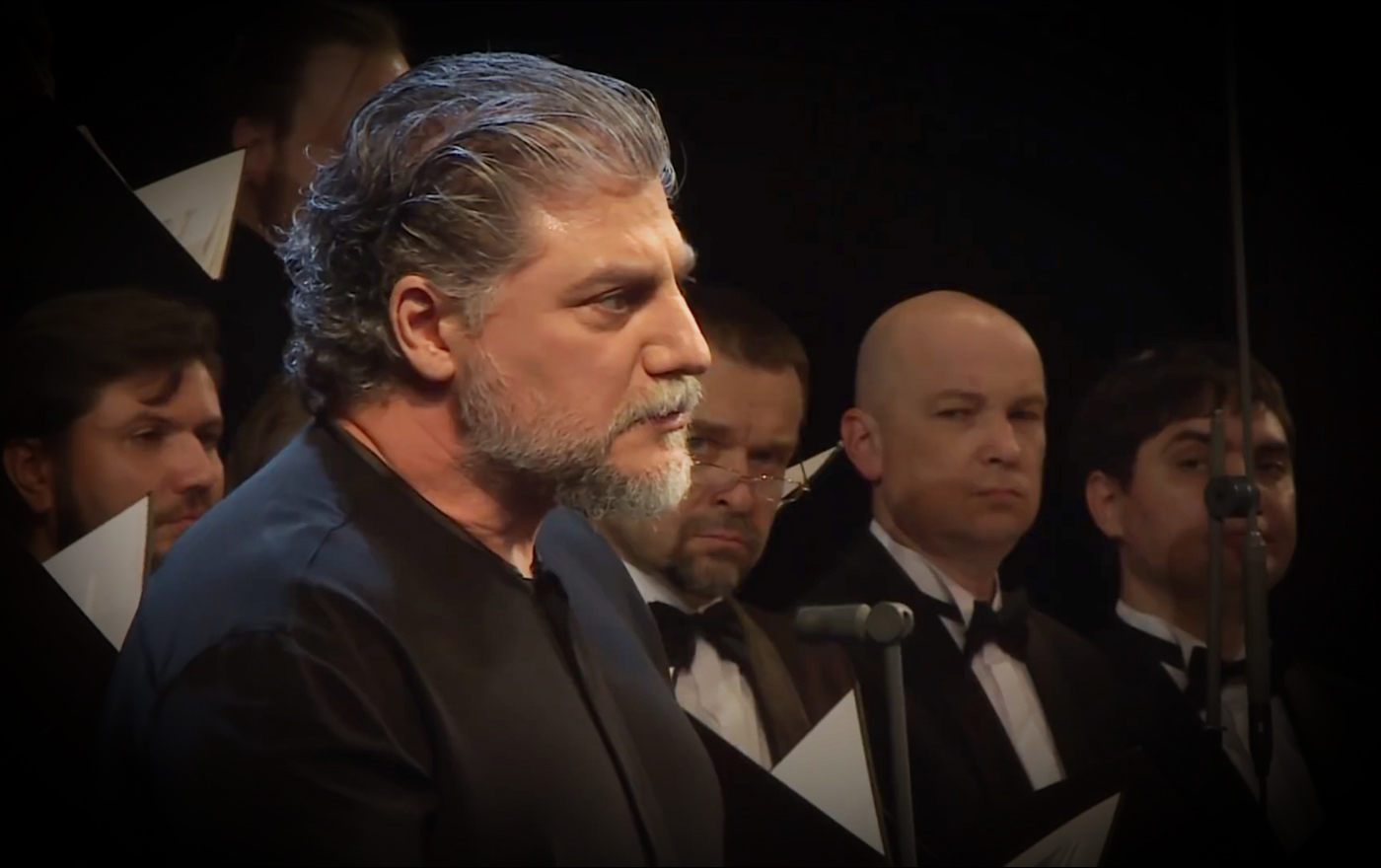

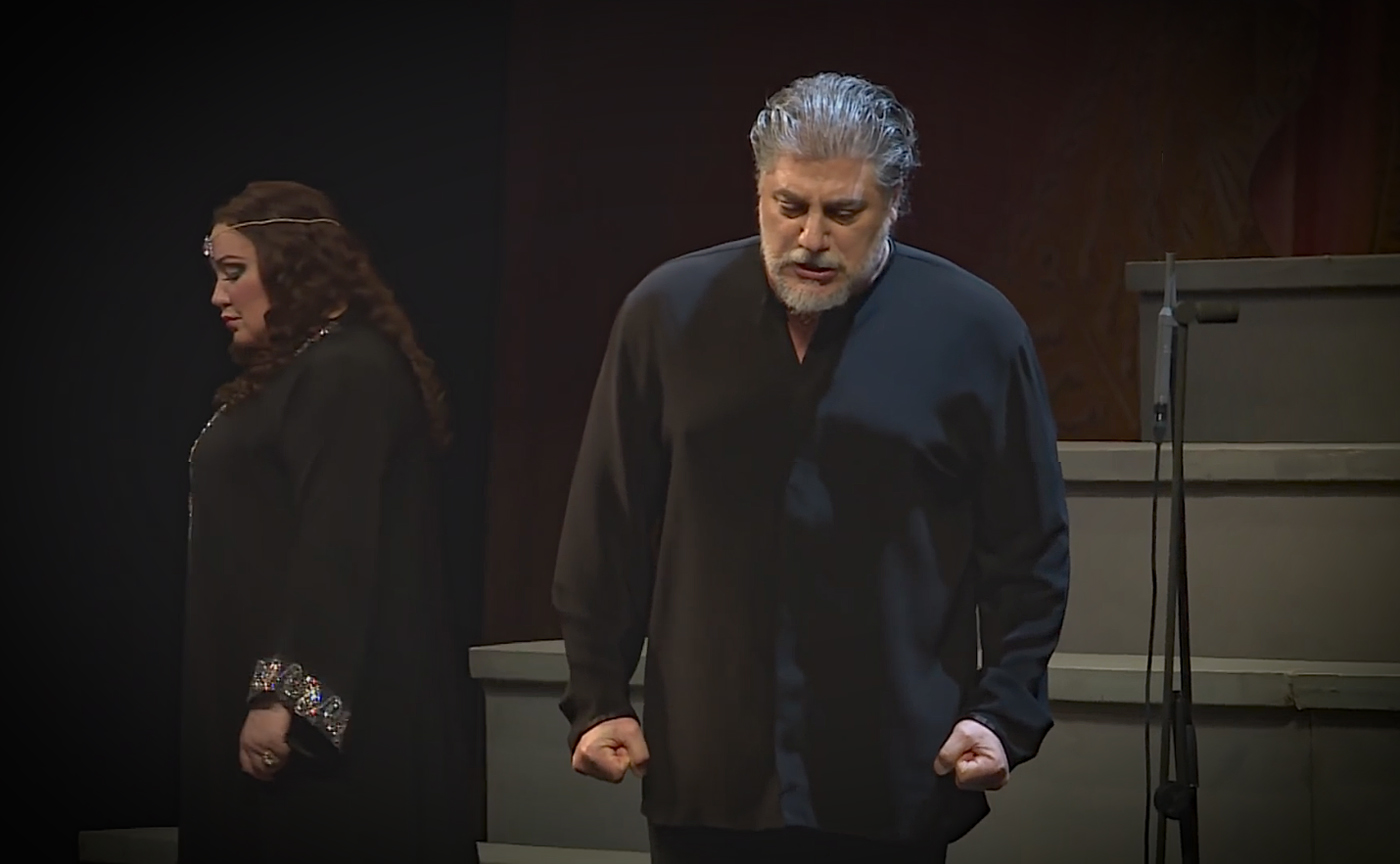

Operatime

Arina

Timofeeva

28 October 2017

Note: This

interview was

actually conducted a

year ago but was

published to

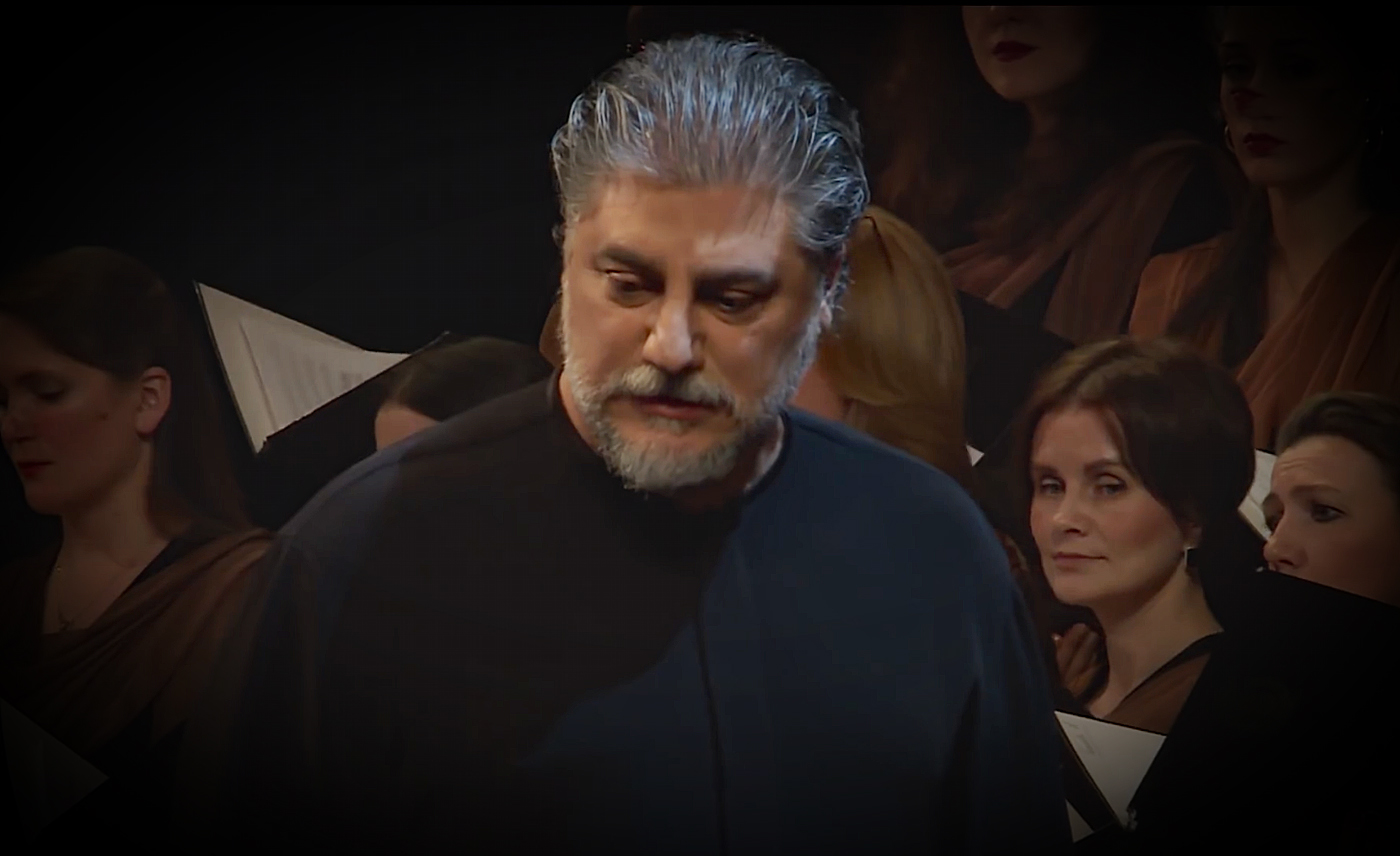

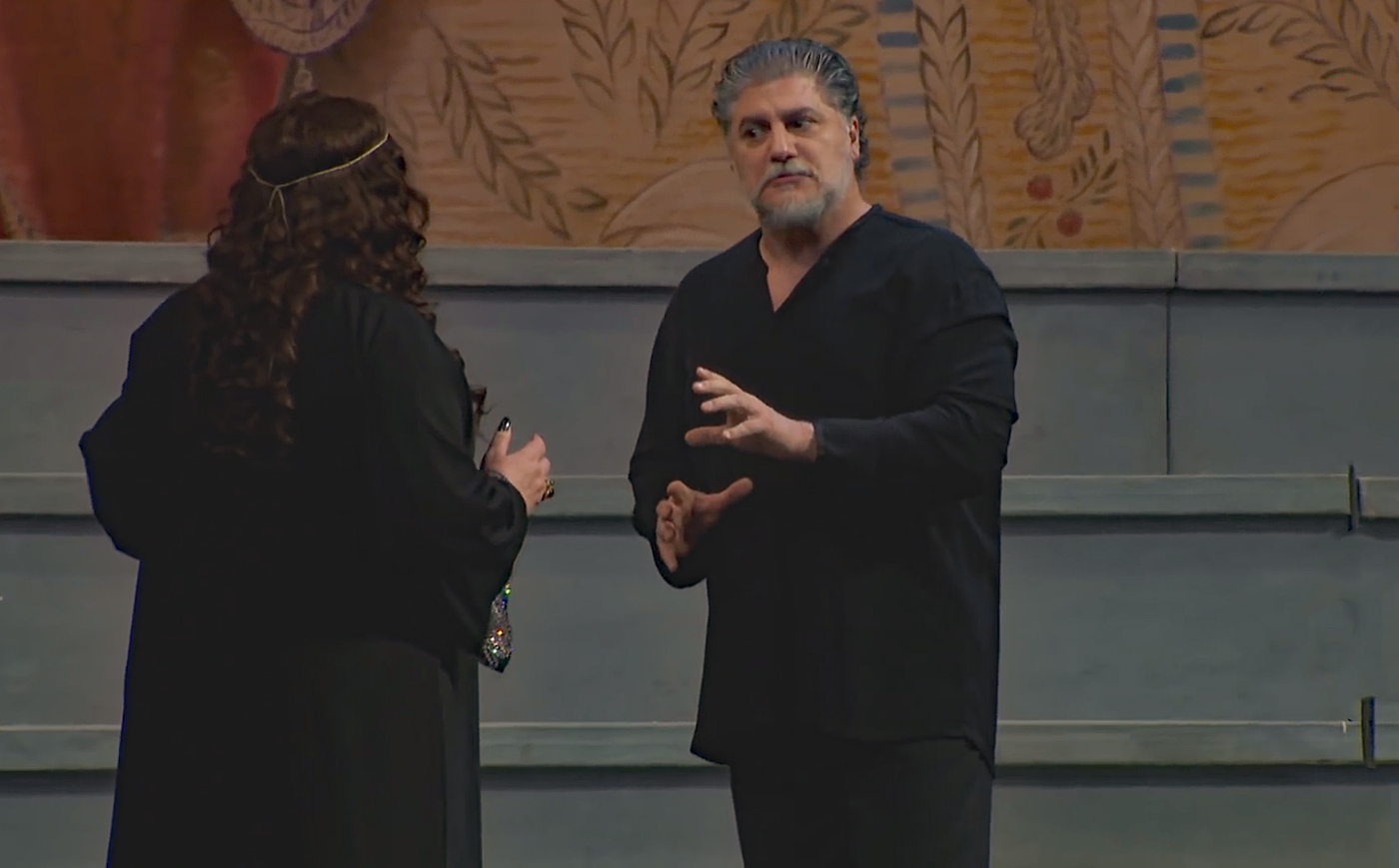

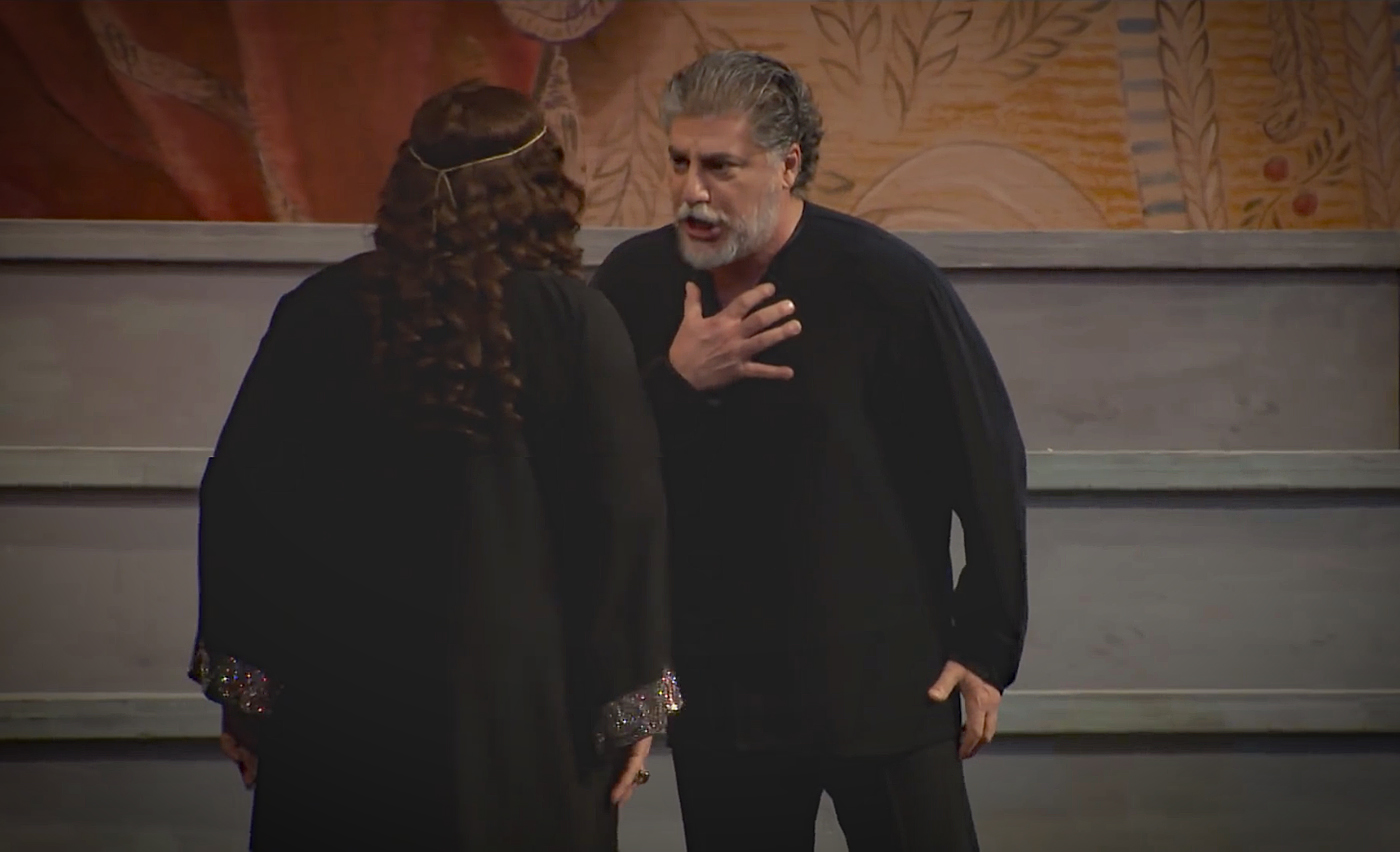

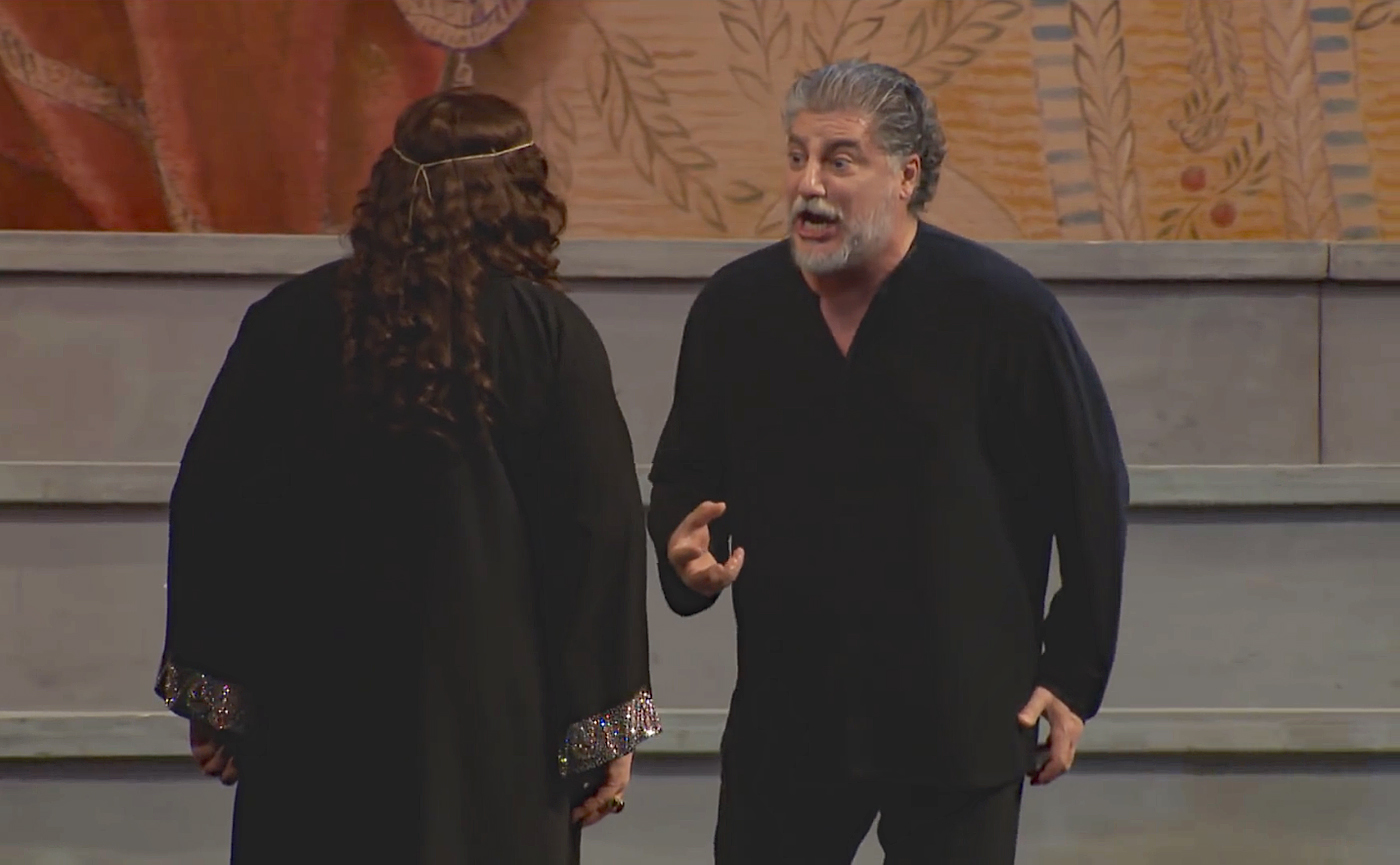

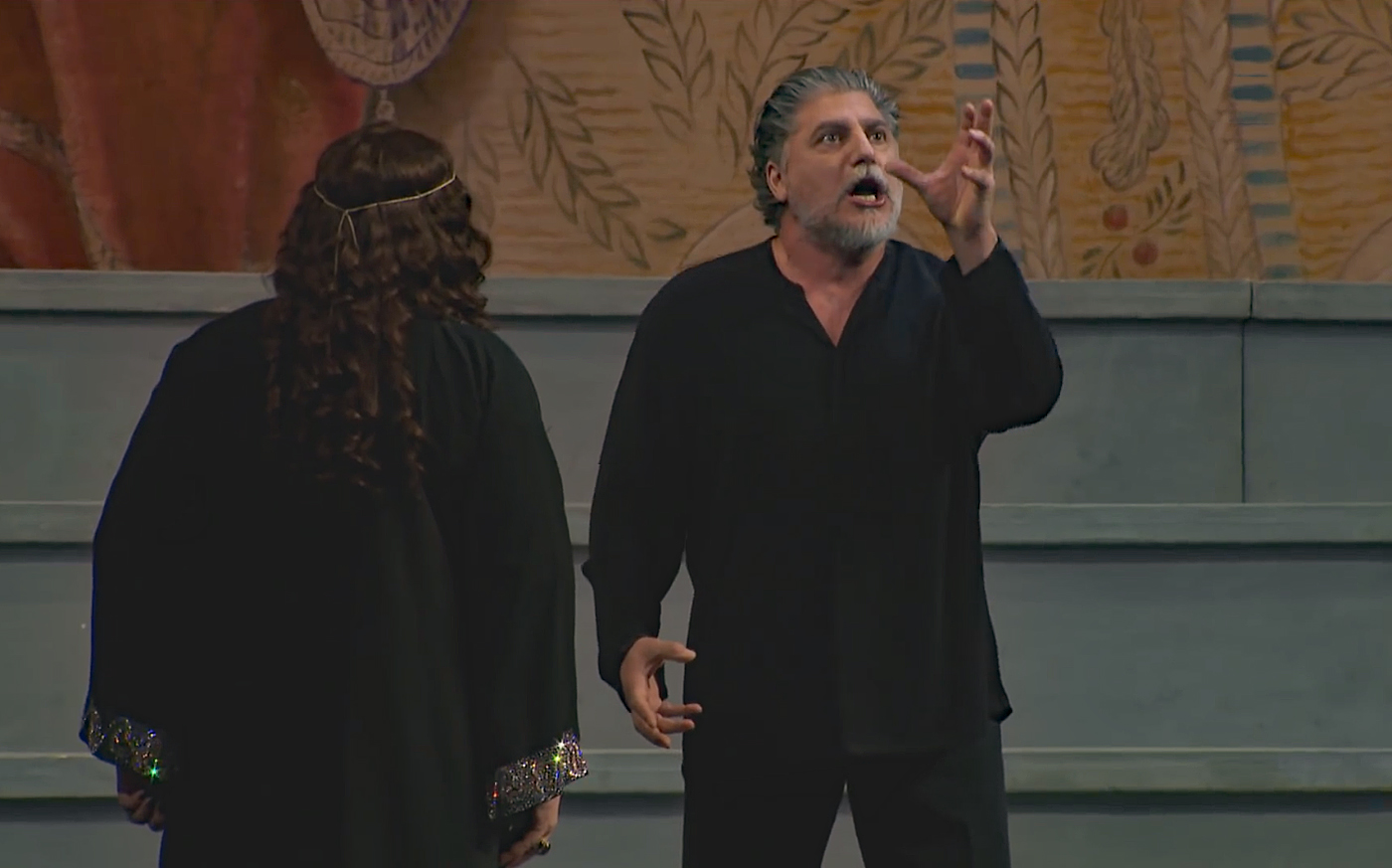

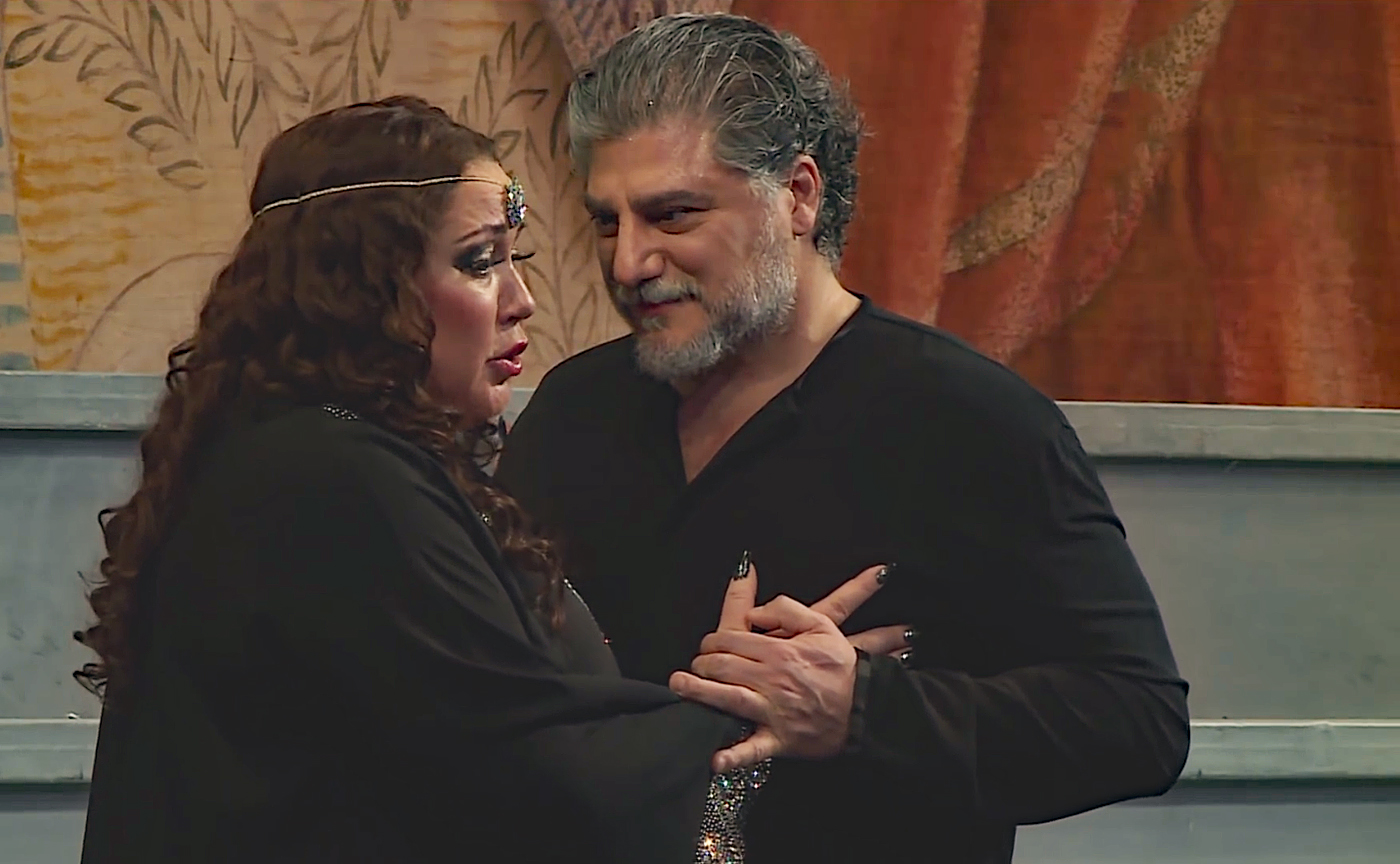

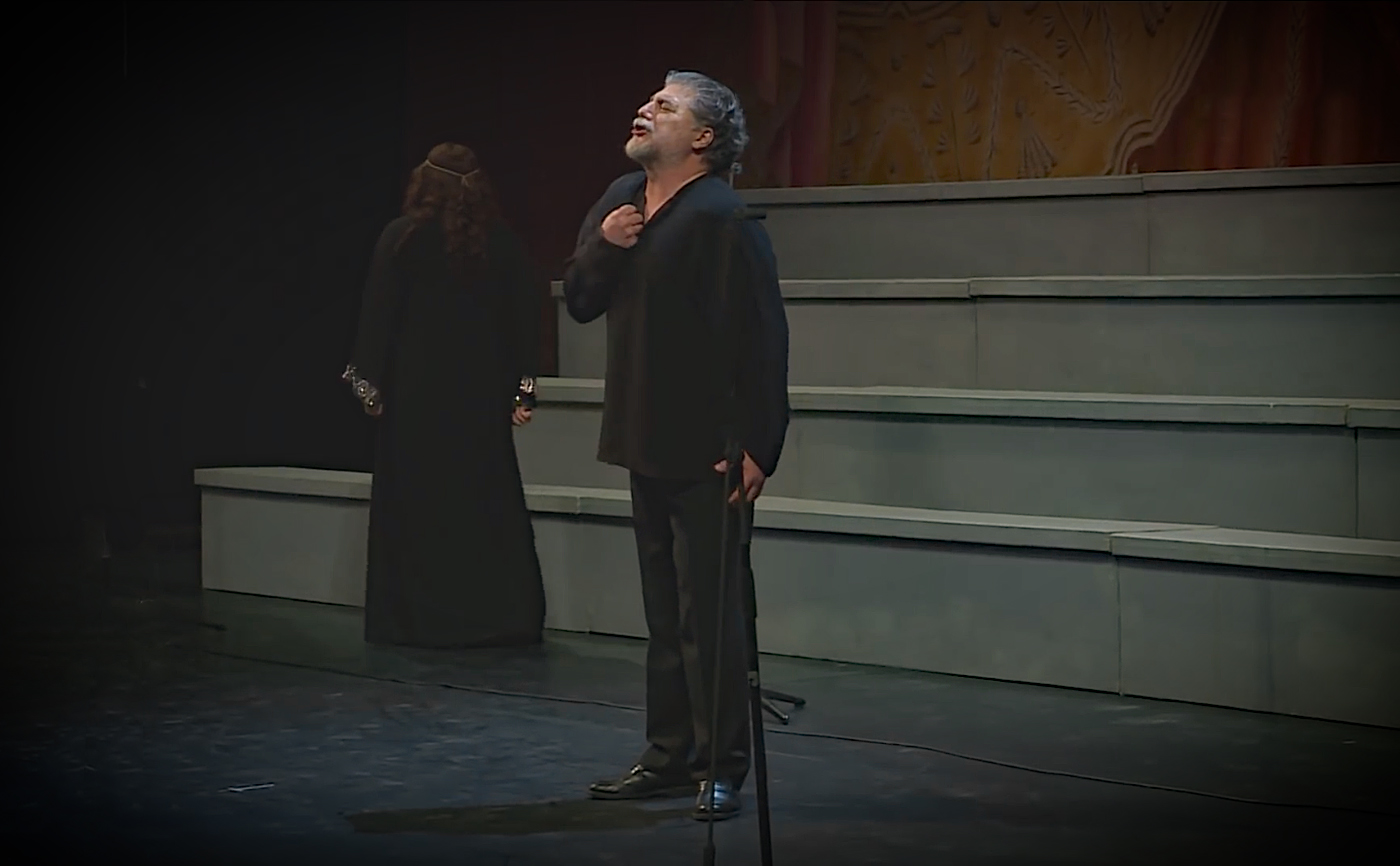

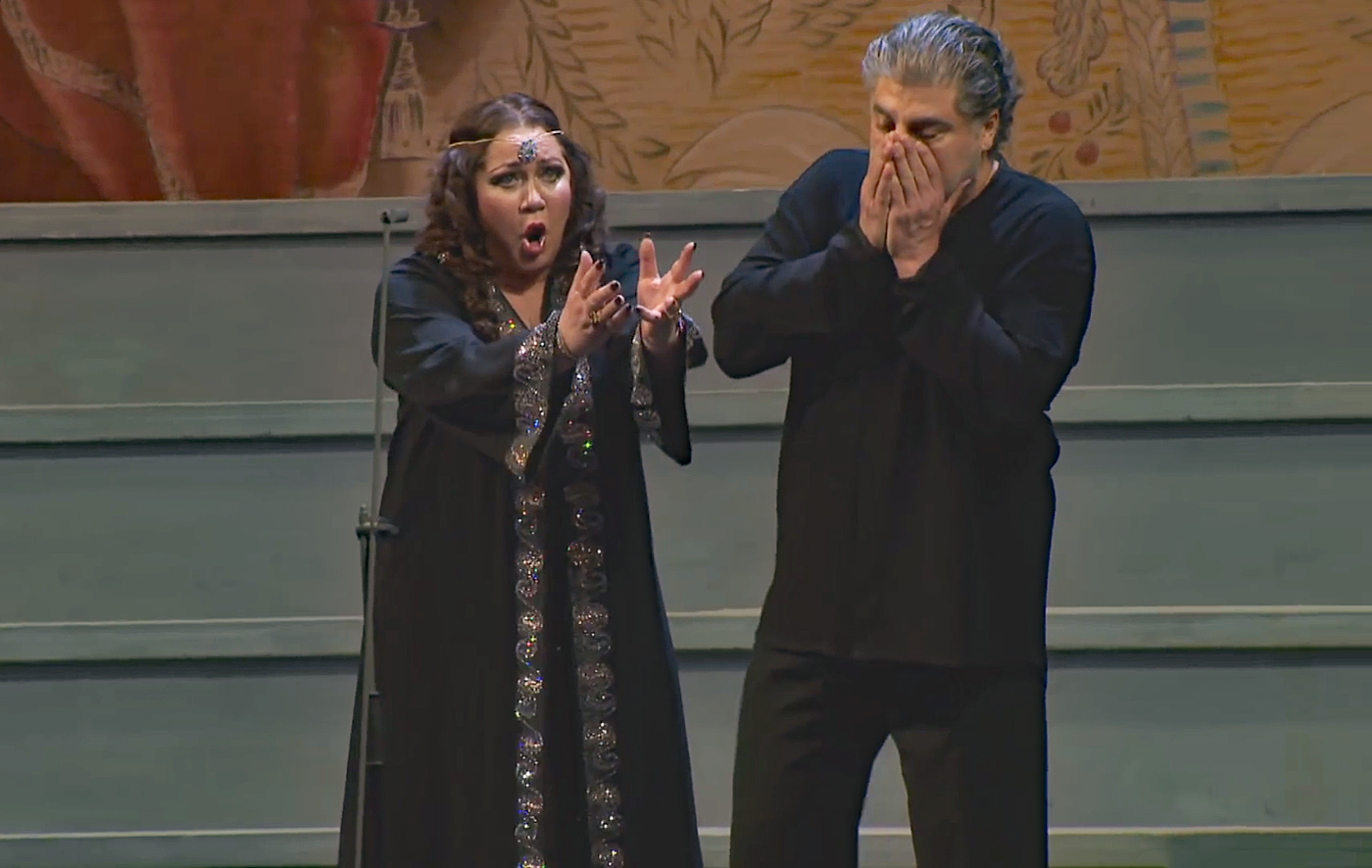

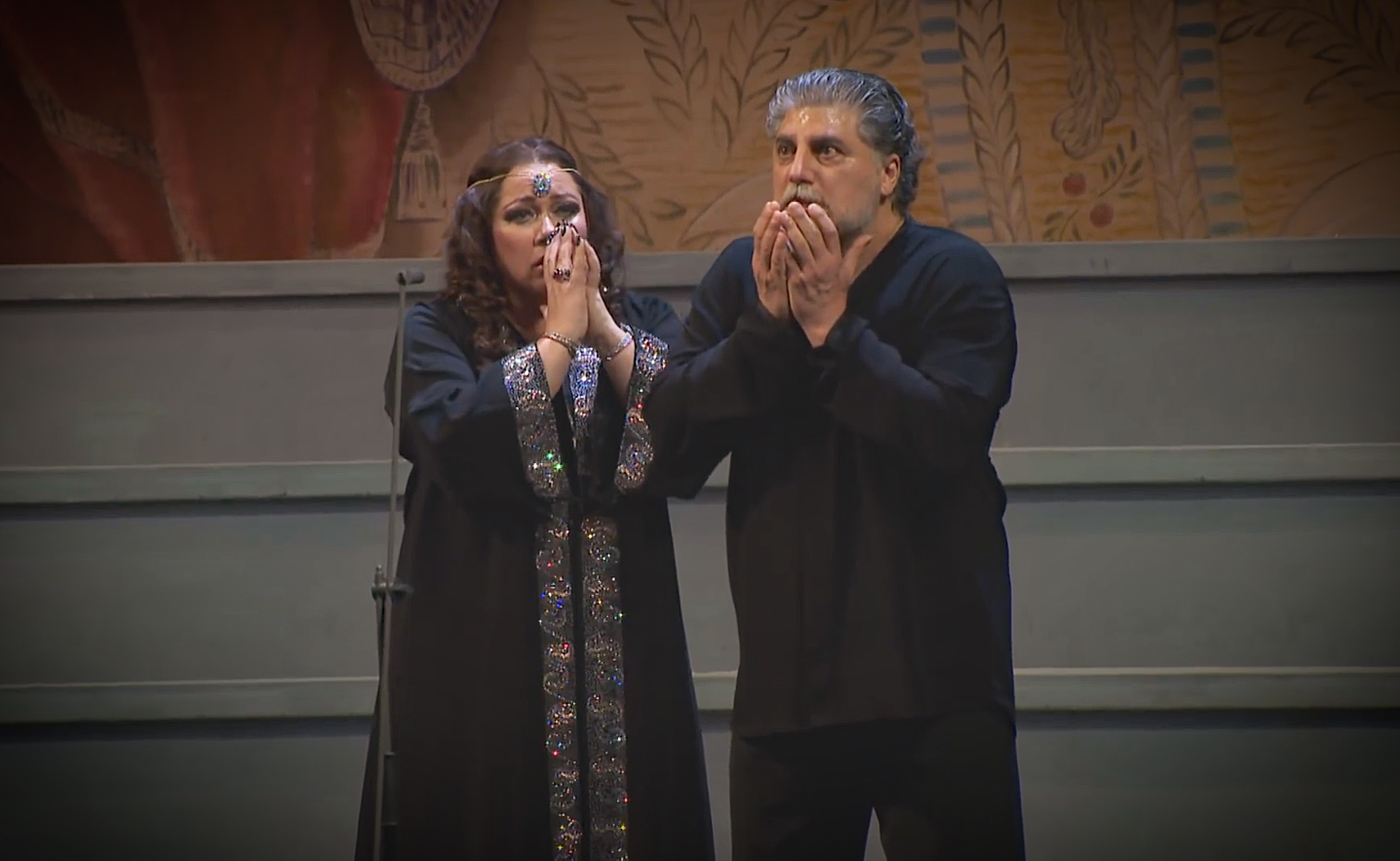

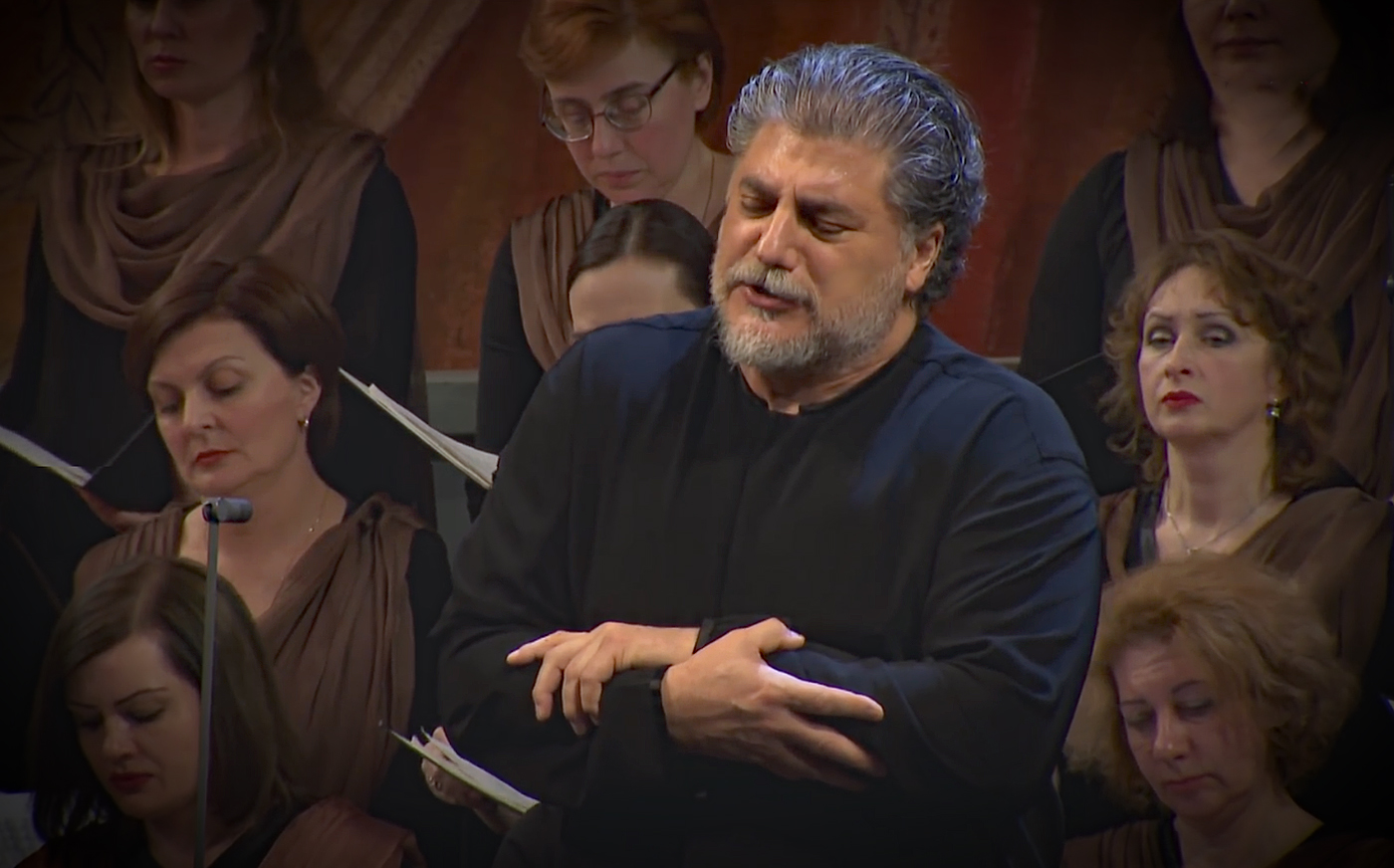

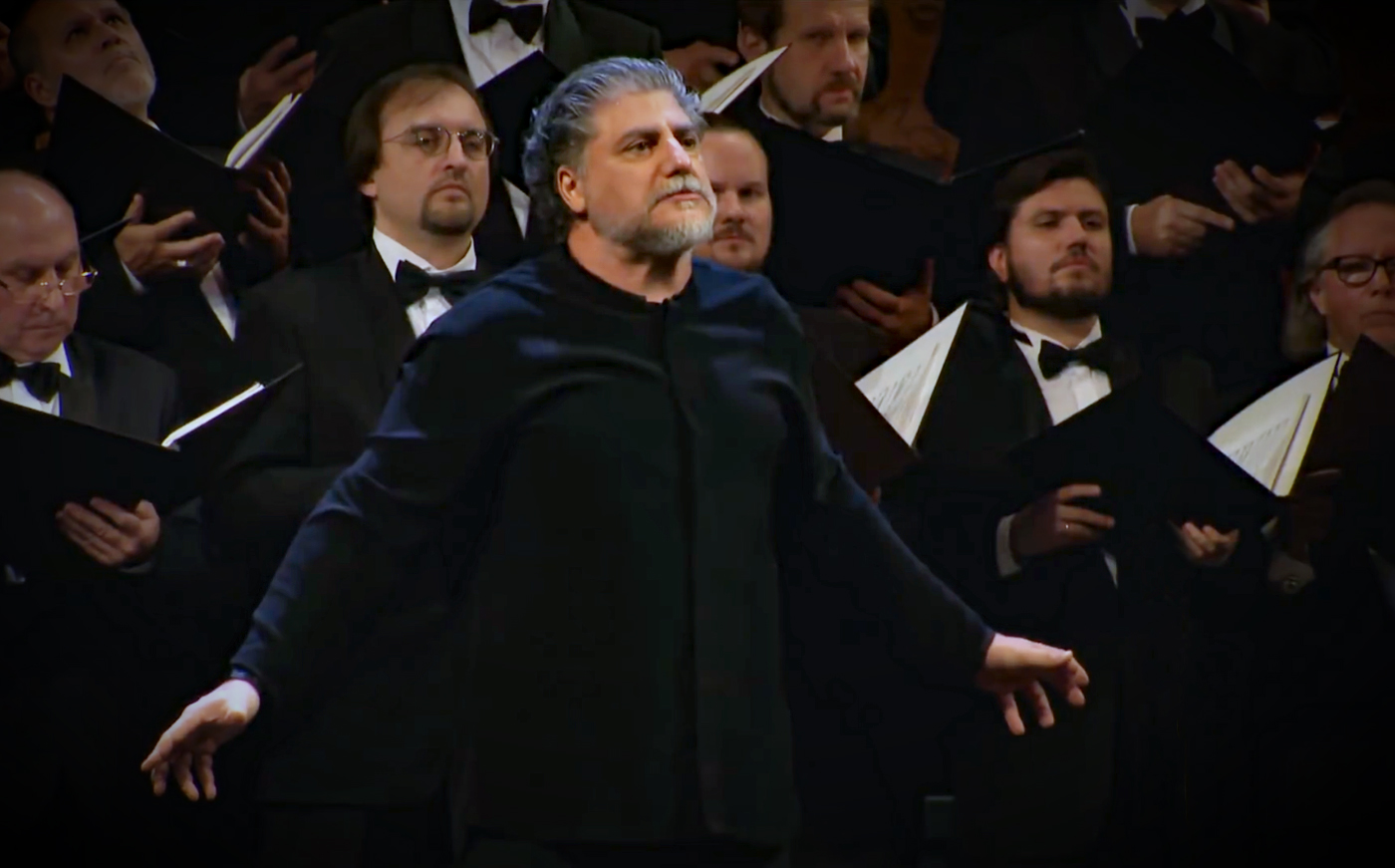

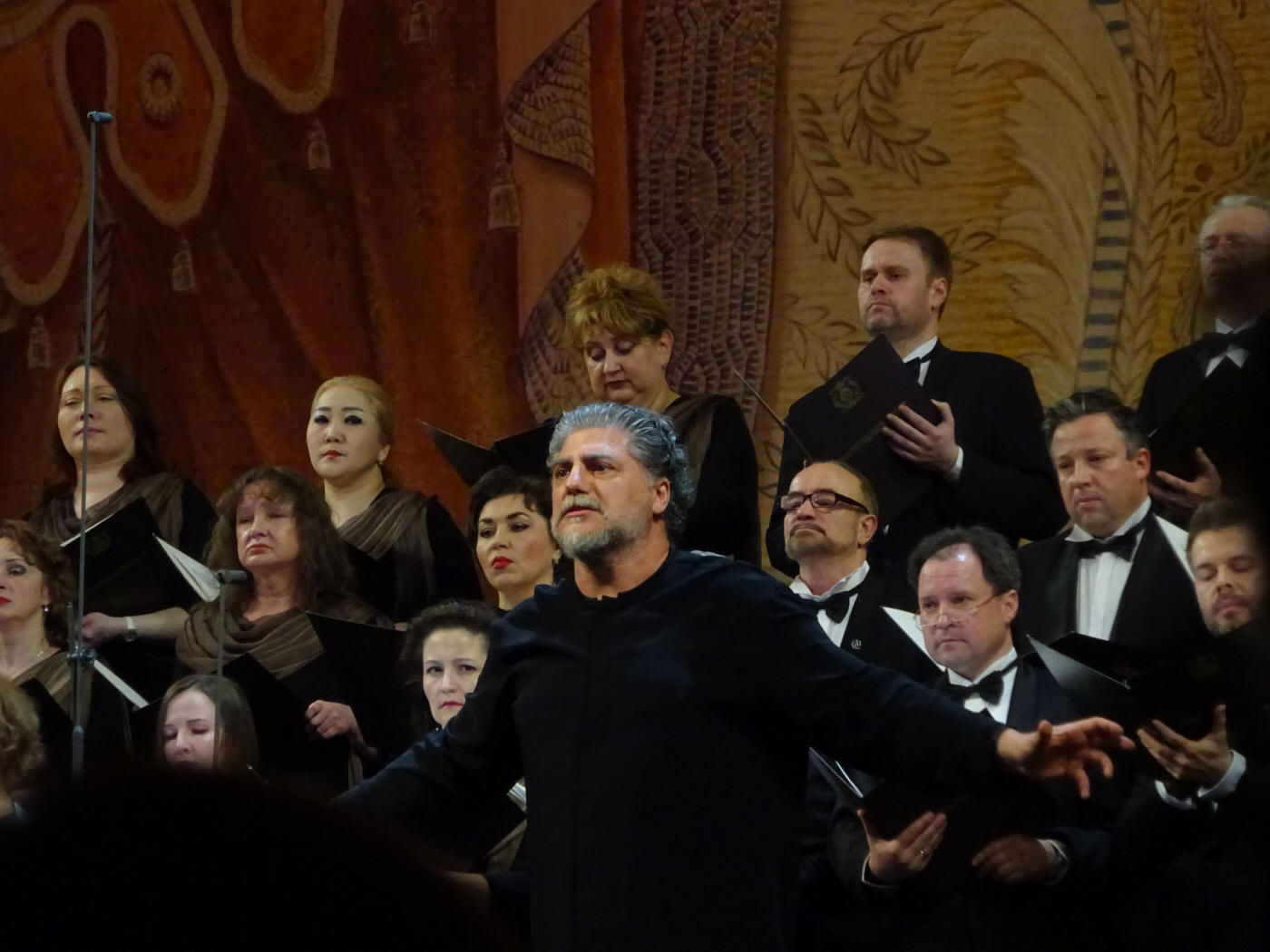

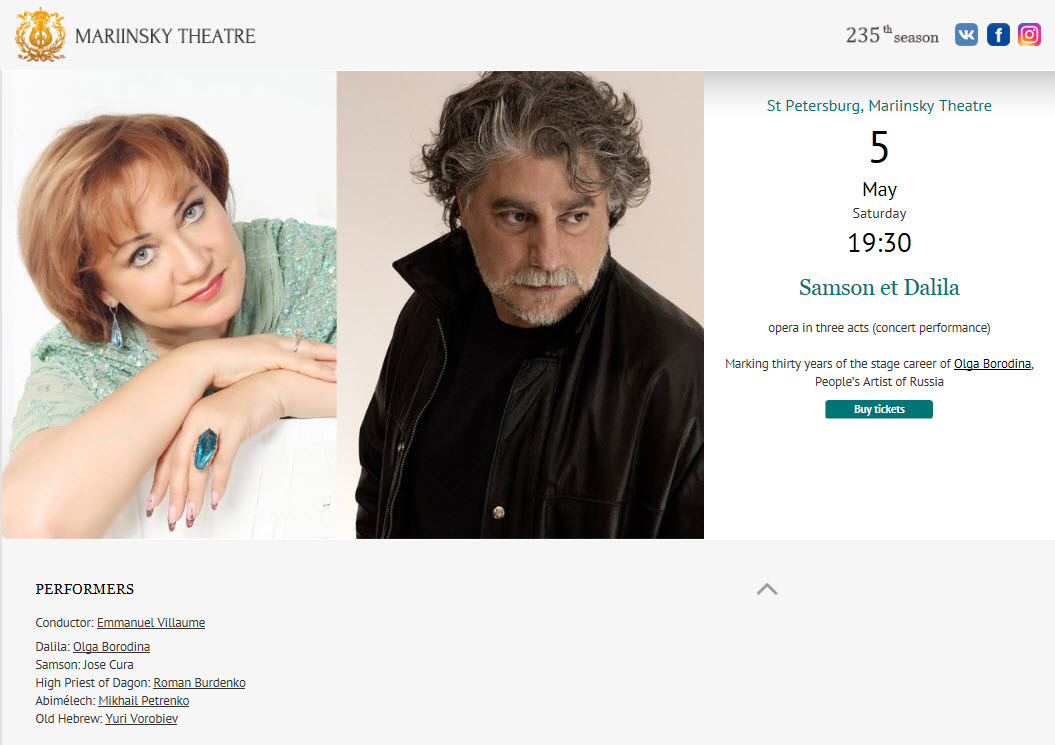

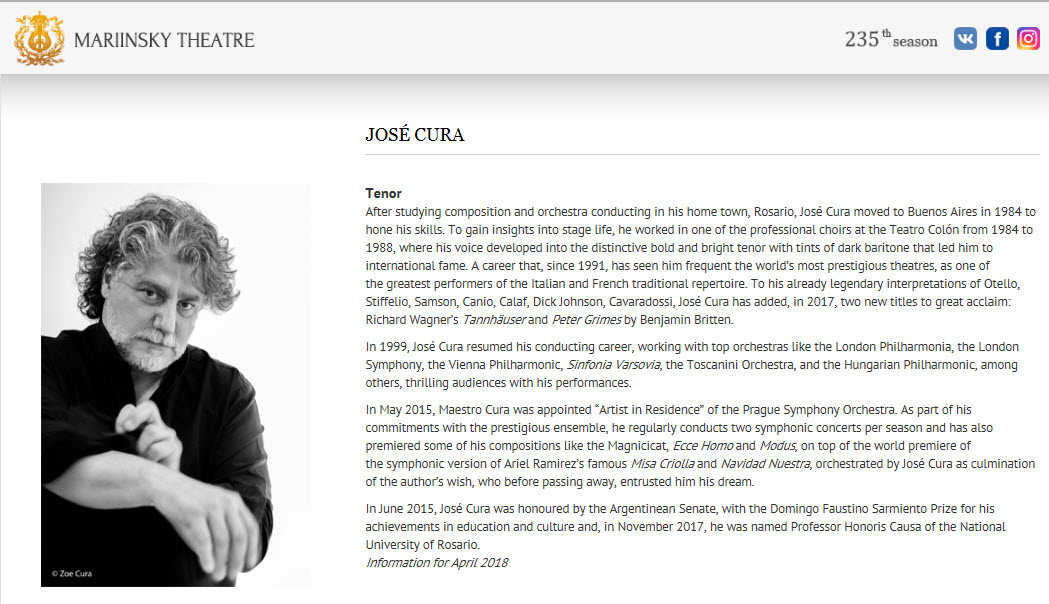

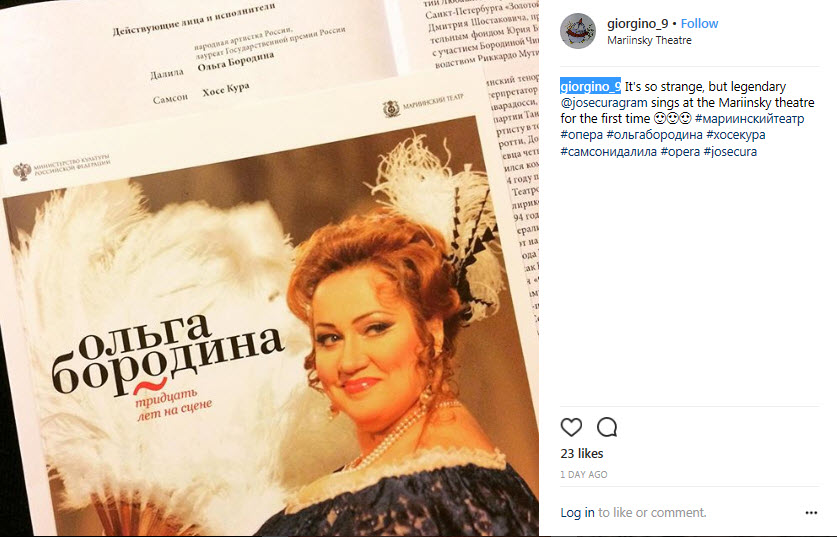

coincide with José

Cura’s appearance

with Olga Borodina

in Samson et

Dalila in St

Petersburg. This is

a ‘cleaned up’

computer translation

so consider it an

approximation of the

discussion.

Q: I heard that this visit is

very short. Would

you like to come to

Russia, to St.

Petersburg again,

maybe for a longer

time?

José Cura: Oh

sure! It would be

great to come to

sing n Russia, where

I have never sung

before (in a

complete opera

performance - AT).

I know that my time

as an opera singer

will end, so it

would be great to

sing one of my

roles—Otello or

Peter Grimes—in the

legendary Mariinsky

Theater.

Q: Let's talk about your

childhood. Was

there music in your

house, were your

parents involved in

music?

JC: My parents were

not professional

musicians but my

father played the

piano. Every

evening, when he

came home from work,

he played a

little—Beethoven,

Liszt, Chopin—just

for his pleasure.

In 1974, he broke

his arm in a car

accident and never

played again. I was

born in 1963 so for

the first 11 years

of my life I heard

piano music at

home…and then it

stopped. But I

always felt

connected with

music. My parents

were always

interested in it.

In those days there

were no records on

CD, there was no

internet, music was

on vinyl. My mother

had a huge

collection of

records: classics,

good pop music,

Sinatra,

Fitzgerald. My

mother did not

discriminate: one

day it could be

Beethoven, another

day - Paul

McCartney. This is

the atmosphere in

which I grew up.

Q: Maybe you have some special

memory from

childhood about a

musical work that

made a strong

impression on you ?

JC: No, I cannot

distinguish one

musical impression.

I heard and listened

to a lot of music.

I grew up in Rosario

in Argentina. I had

a normal childhood.

I remember that I

was in the theater a

couple of times, I

listened to concerts

for a guitar, maybe

it was the beginning

of my interest in

this instrument, but

I do not remember

any one event that

would have made an

indelible impression

in childhood.

However, I can say

with certainty that

when I was a

teenager, I had a

musical idol - the

legendary guitarist

Ernesto Bitetti. He

is also from

Rosario, and my

family was friendly

with his family, we

talked, visited each

other at a party.

Now he is retired,

but in the last

century it was one

of the most famous

guitarists in the

world.

Q: Do you remember the moment

when you decided

that music would be

your profession?

JC: When I was 7 or

8 years old, my dad

sent me to learn to

play the piano. The

teacher was a very

nice elderly woman,

she tried to teach

me how to play but I

was just a child,

quite active and

unpredictable. And

after three or four

lessons she sent me

home, saying that I

was still too young

and not at all

interested in

music. After the

piano, I radically

changed direction

and began to play in

rugby, which, of

course, had nothing

to do with music. I

played rugby for a

long time, almost

becoming a

professional

athlete. But when I

turned 12 and went

to high school, I

had a classmate who

played the guitar.

Playing the guitar

and singing songs

seemed to please all

the girls. And I

thought that maybe I

should also learn

this. I studied, I

sang the Beatles

songs. And when I

was 14, I told my

father that I liked

playing guitar and I

would like to learn

this seriously. I

started studying

with a real teacher,

so it all started.

Q: And how did the transition

from guitar to

composition, vocals

and conducting?

JC: The guitar is

an amazing

instrument. To this

day, it is the only

one I truly love.

But over time I felt

that the guitar was

too quiet an

instrument for my

extroverted nature.

I needed something

more. I told my

father that I wanted

to study at the

conservatory and to

be a composer and

conductor. Among

other courses in the

conservatory was a

vocal course, and it

turned out that I

have a voice. I was

about 20 years old.

I've always sung,

but it was never an

operatic-style

singing.

Studying to be a

conductor helped me

to discover I have a

voice but I was not

then thinking about

making singing my

career. I studied,

I sang in the choir,

I earned a little

money with it, but I

continued to study

conducting and

composing music.

When I was 22,

Argentina passed

real elections after

many years and the

country returned to

democracy. This was

the beginning of a

new era but these

were very difficult

times: orchestras,

choirs had problems

with funding. It

was difficult to

survive and to make

a living as a

conductor and

especially as a

composer it was

almost impossible

(even now it is

impossible to earn a

living as a

composer, perhaps

only composers who

write music for

films somehow do).

And I was 24 years

old and I thought

that I could sing

and maybe find a job

related to singing:

weddings, parties or

a professional

choir. I would work

[singing] to support

my work with the

composition. I

started singing in

the choir, going to

the auditions.

Now I can say that I

am happy that I have

recognition as an

opera singer but in

addition I have

written music, I'm

conducting, and

still sing.

Q: Now you are a composer, a

conductor, a singer,

a director, a

choreographer, and a

photographer. Do

you have any plans

for the future? Do

you plan to develop

all these interests?

JC: Nobody knows how

everything will

develop. First of

all, no one knows

what will happen to

him in the future:

what will happen to

health, how

circumstances will

develop. Now I feel

healthy and young,

but every year I

feel that I should

not work so

intensively. I used

to give 100

performances a year,

and now I feel that

I need more time to

recover. You just

need to be prepared

to react and adapt

to any situation

that life can

bring. This is one

side. The other

side is dreams. Of

course, I dream to

continue singing for

as long as I can,

but it depends on my

body. Some can sing

for a long time,

some cannot. It

also depends on how

much you've sung

throughout your

career. For

example, on average

over 25 years of

career someone can

give 1000

performances. I

have already given

2500. If we draw an

analogy with cars,

that is, two cars

from 1990, but one

has driven 50

thousand km and

another 500

thousand. Two

identical machines,

but one of them was

operated much more.

So let's see how my

body "behaves." But

my dream is, of

course, to conduct

and compose music,

because it all

started, and to

return to this would

be a wonderful way

to complete the

cycle.

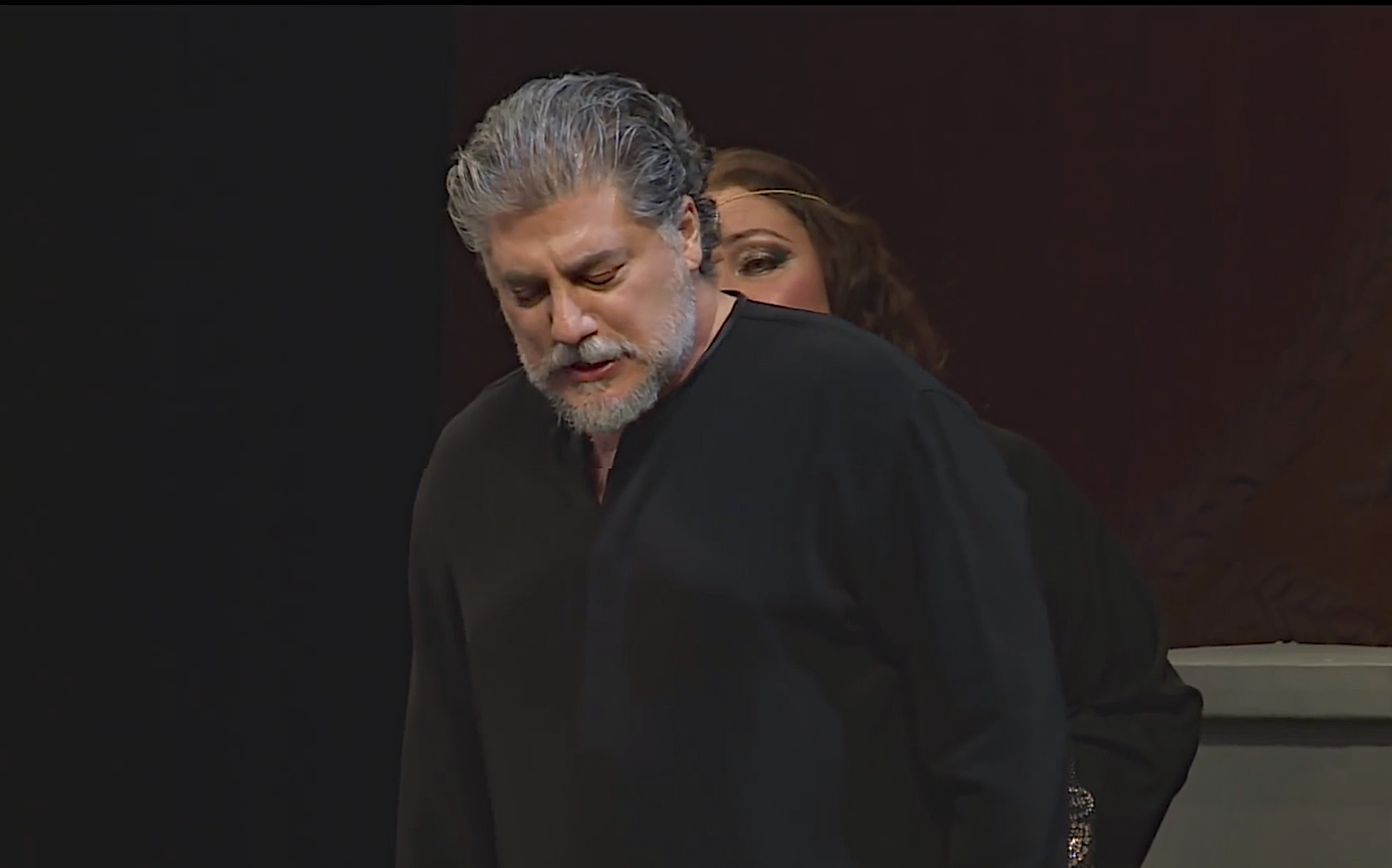

Q: Let’s return to the operatic

career. Do you have

a favorite opera

hero, a favorite

opera part?

JC: I will answer

the way I always

like to answer: my

favorite role is the

one I'm working on

right now, the one

I'm singing now. In

other words, after

all that I have

done, and this is a

lot of roles and a

lot of performances,

if I go on stage,

then I go out in a

role that I really

can perform and

which I really enjoy

performing. I do

not go out on stage

for the sake of

profit. When you

are young, you have

to make a living,

you have to be in

the profession, then

there comes a time

when you can say: I

can sing this role

very well, and in

this role I'm not so

good, so it is

better not to take

for it.

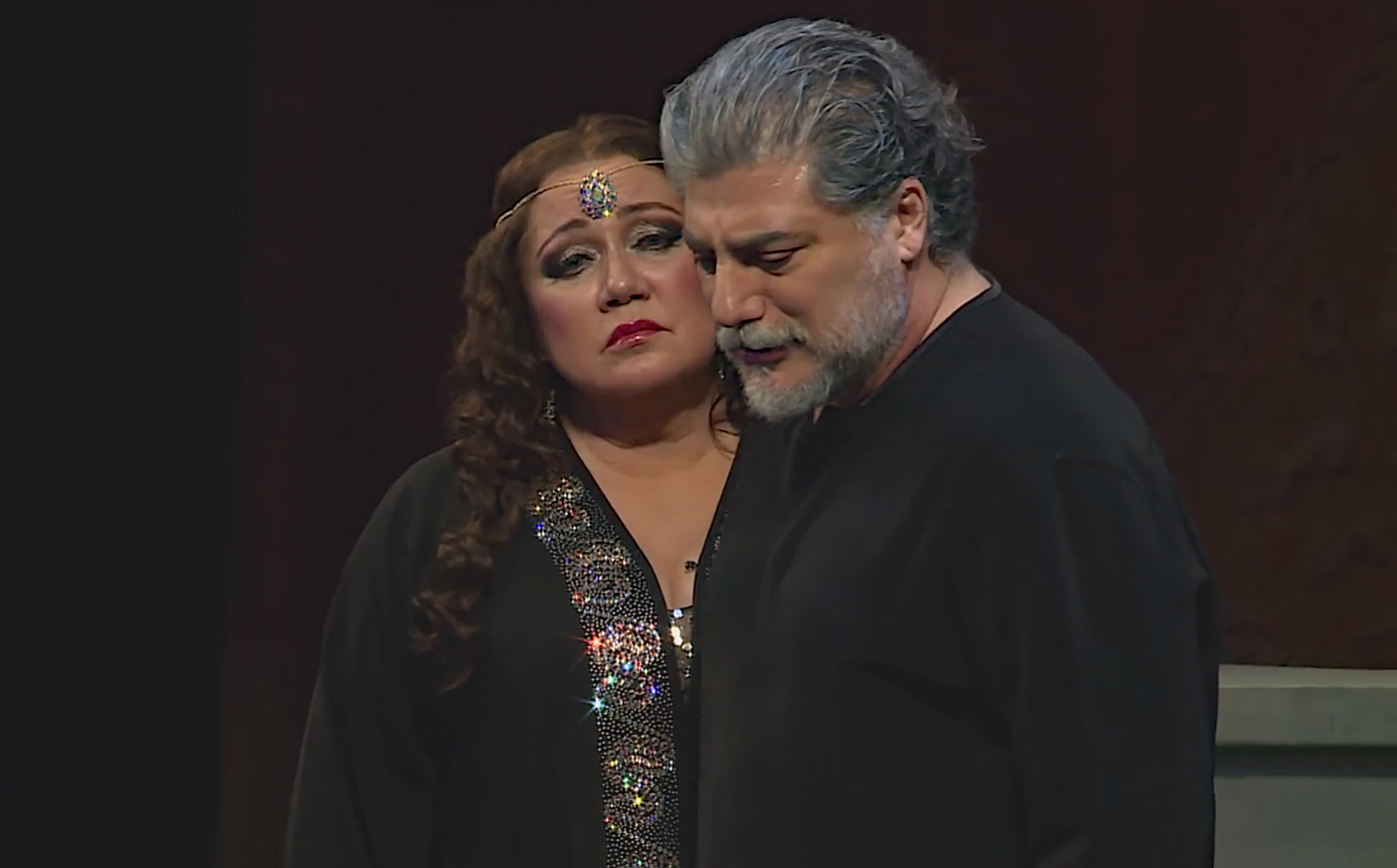

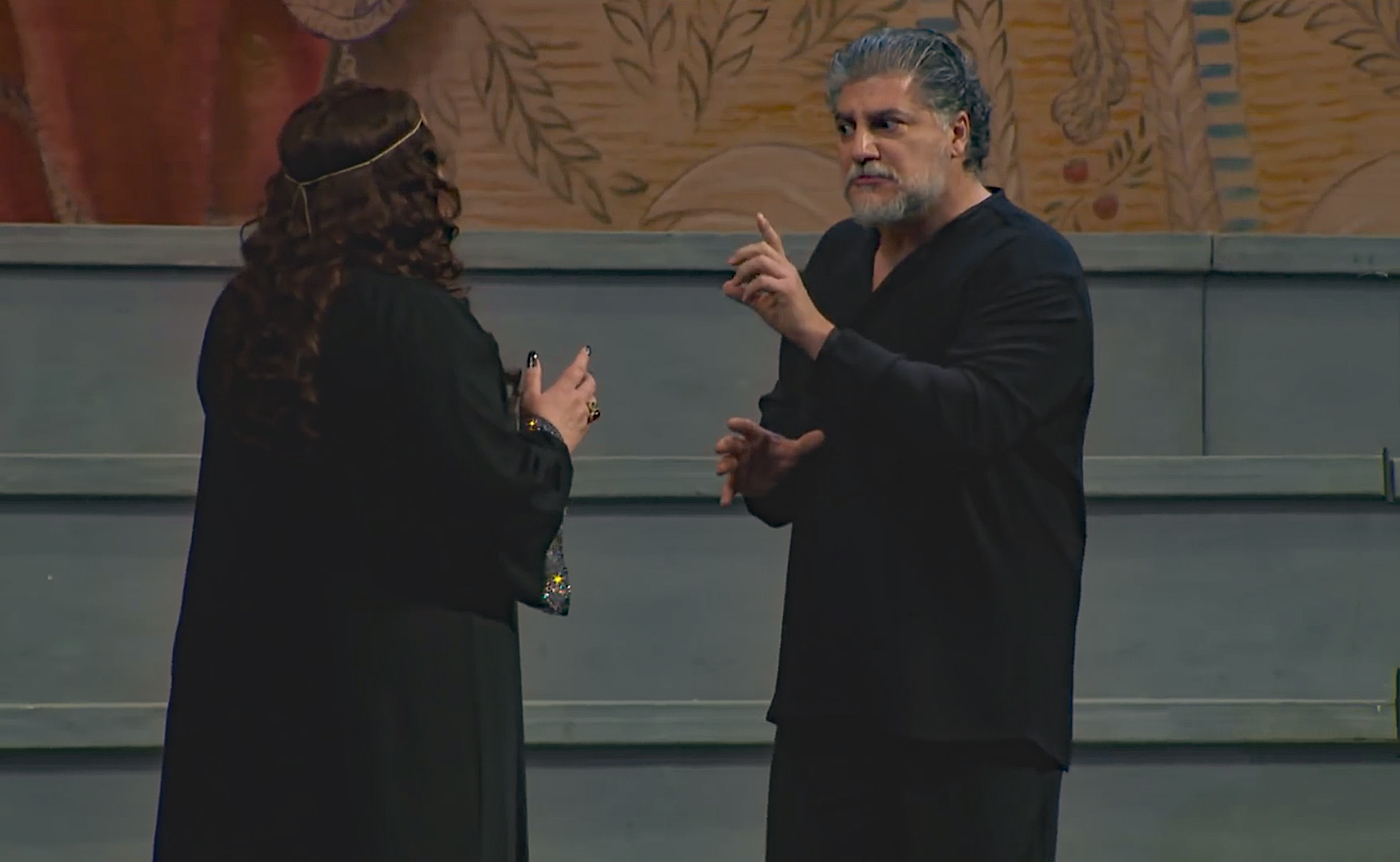

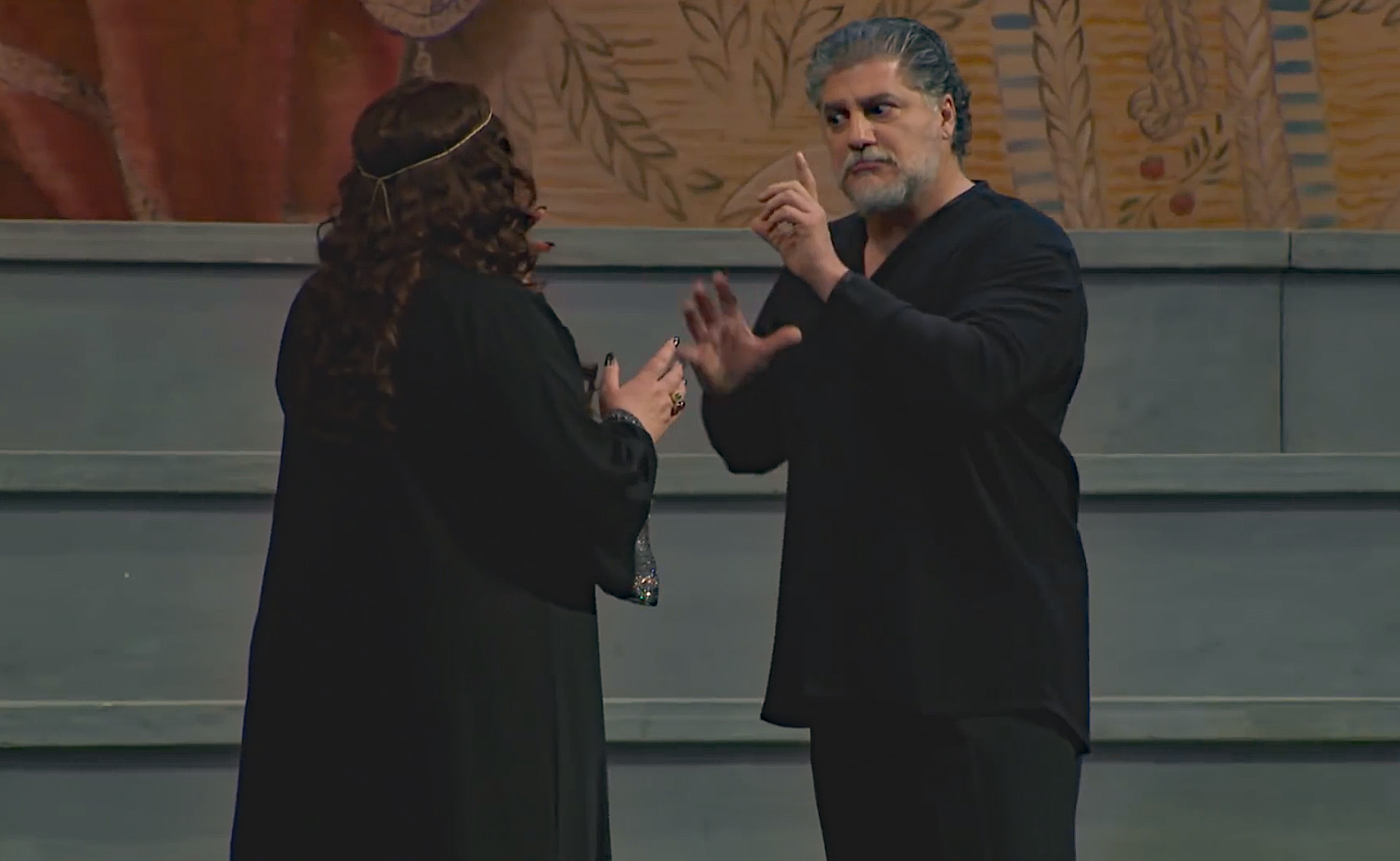

Q: Can you name colleagues with

whom you are very

comfortable singing?

JC: Of course I

will not give you

any names, because

it can lead to

conflict. For me to

be with someone on

the stage, working

together is like

dancing in a couple

or making love. It

should be very

comfortable, there

must be interaction,

moments when you

lead, then those

when the partner

leads. This is the

perfect partner for

me on the stage.

Sometimes there is a

partner who "does

not know how to

lead" or "steps on

your feet". This

has rarely happened

to me. There is

nothing more

terrible in dancing

than when a partner

steps on your feet.

It hurts. And then

you have two

options: you either

stop dancing or you

start to lead, and

then everything goes

well. Depending on

the situation, you

must decide how to

proceed. I have

been lucky that

during my work I

never had to "stop

the dance."

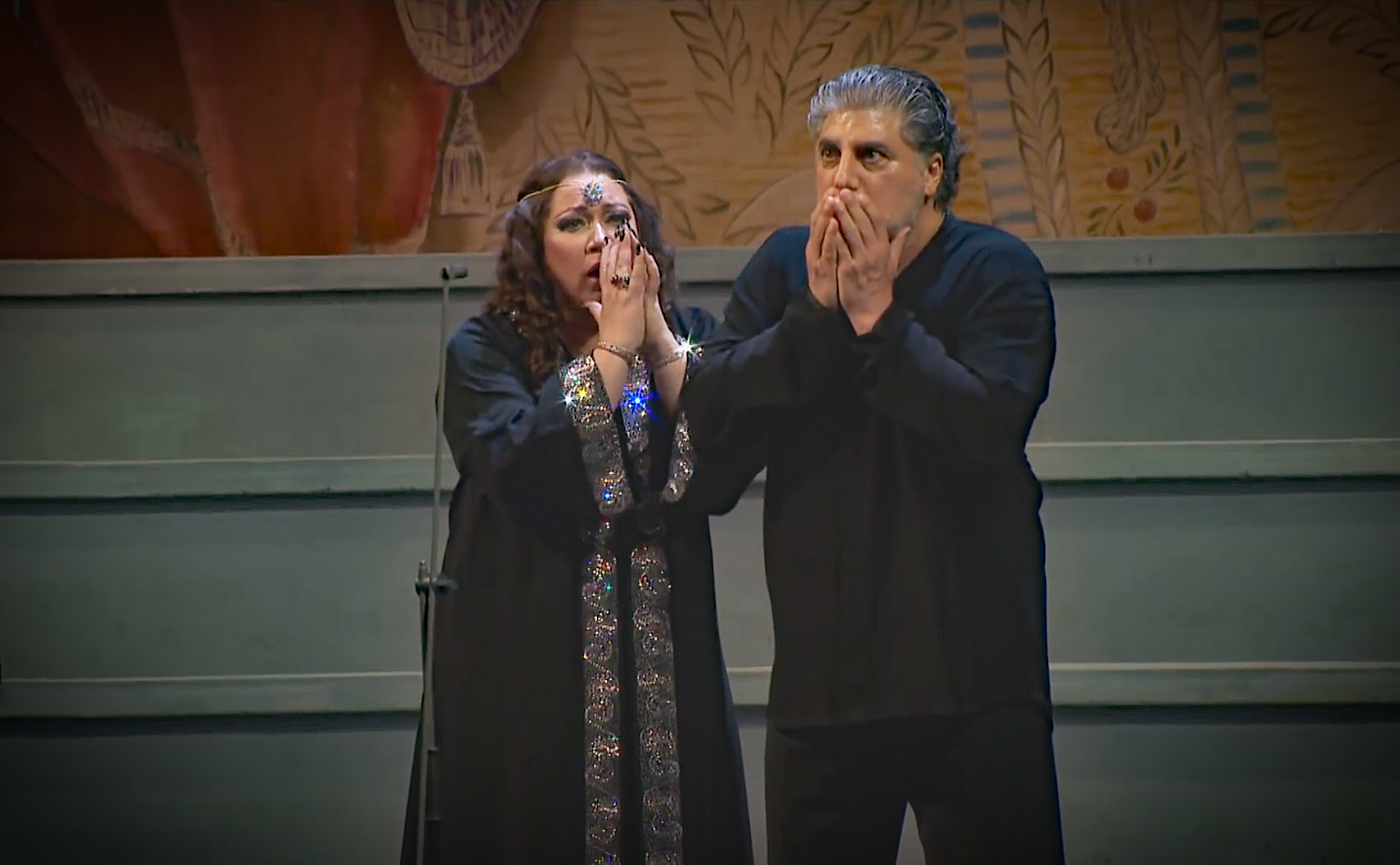

Q: I know that you sang with

Anna Netrebko. Did

you work with other

Russian singers and

singers?

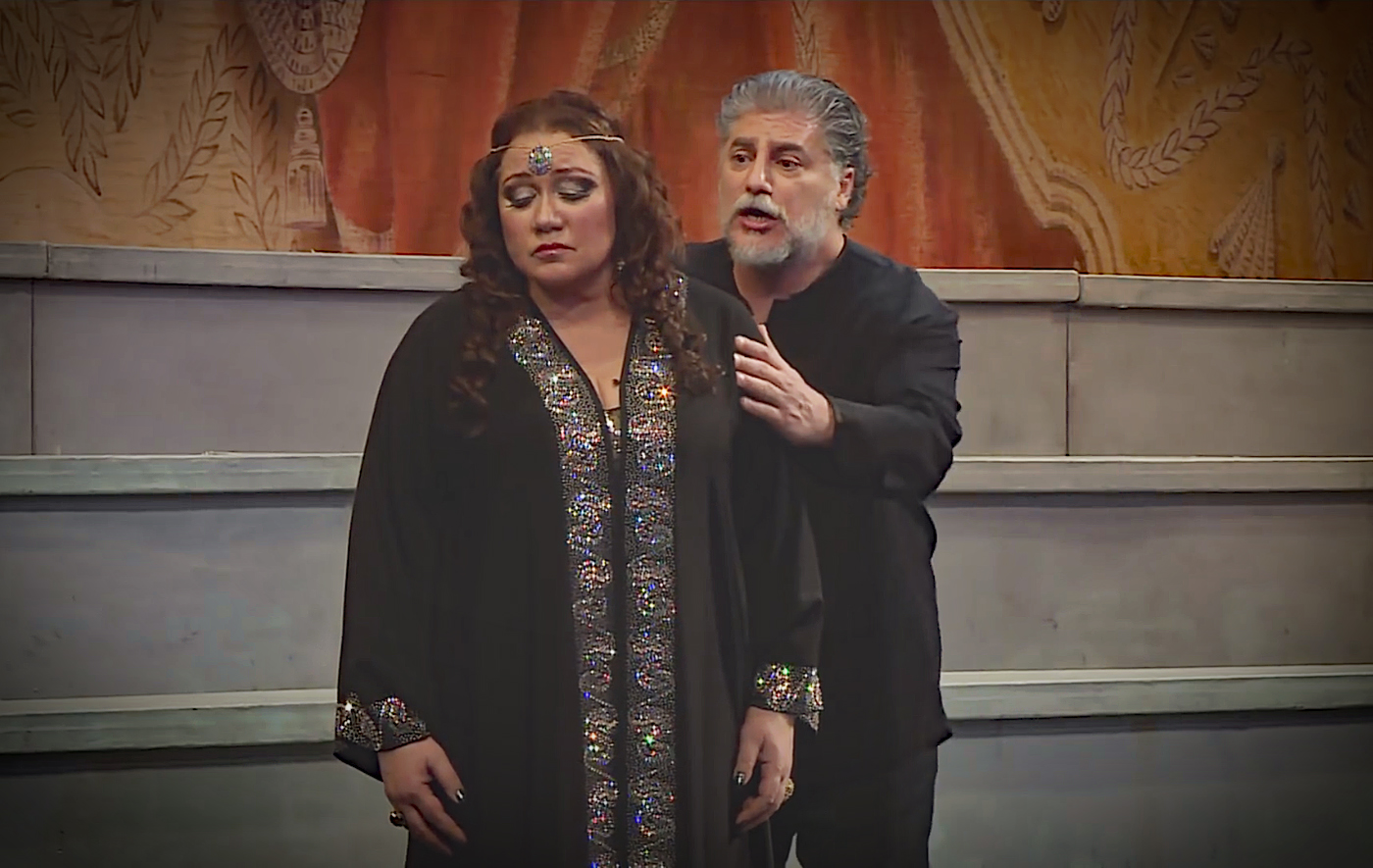

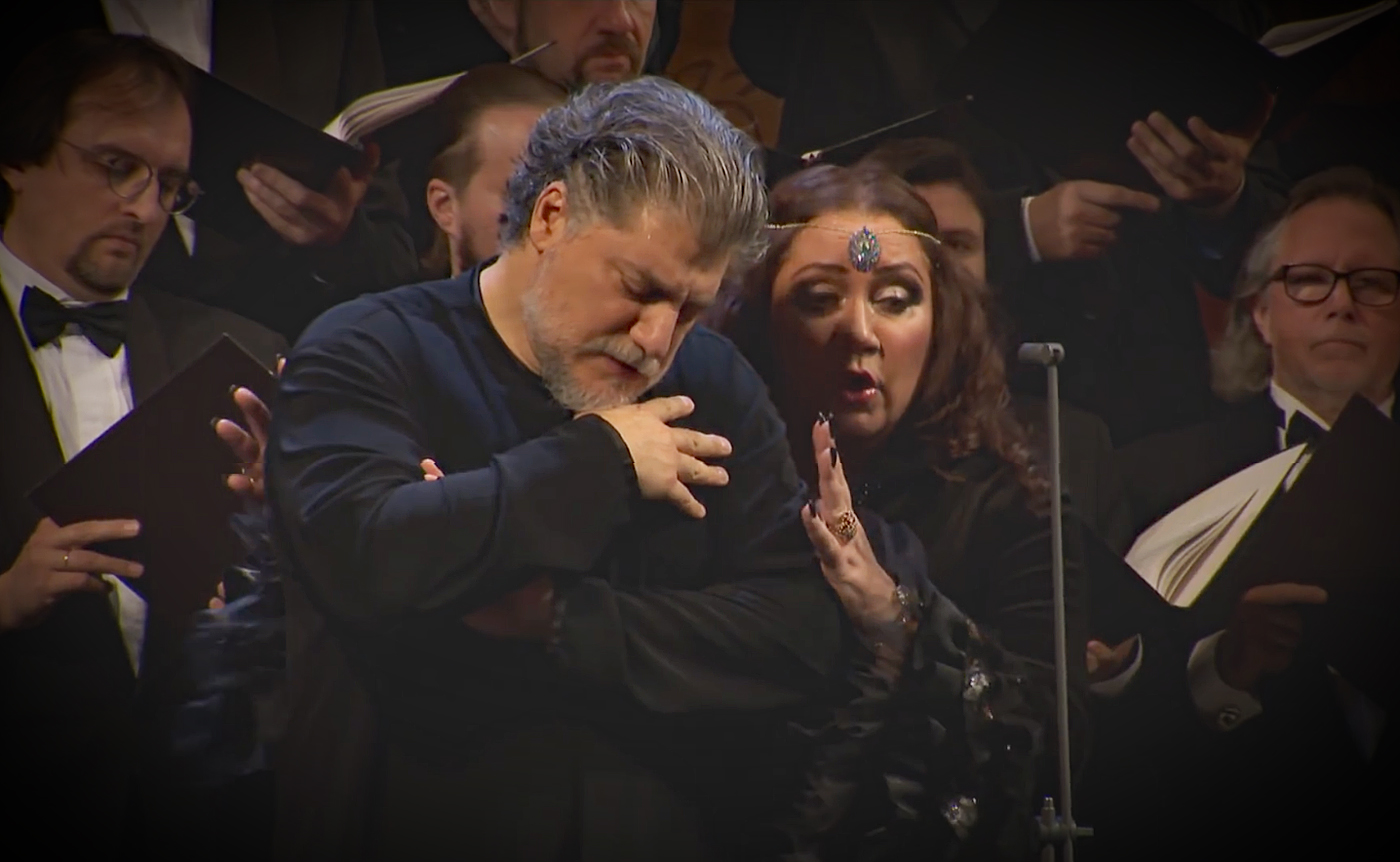

JC: Yes, of

course. Two Russian

singers with whom I

sang a lot are Marie

Guleghina and Olga

Borodina. I met

Maria in 1995, so

that is already 22

years we have been

singing together. I

met Olga in 1998,

she sang her first

Carmen with me. We

were practically

children. Since

then we have sung

together, made

records, grown older

together, watched

our children grew up

together. I knew

her daughter when

she was a little

girl, and now she is

a young woman. And

of course, I was

familiar with Dmitri

Hvorostovsky. I

know his family.

I’ve know his

children since their

birth.

Q: You said that when you sang

Otello, then your

partners were ,

among other things,

young singers who

performed this role

for the first time

working with you .

JC: Yes, we can

say that I

"baptized" at least

20 singers for the

role of Desdemona

and also many

singers who

performed Iago for

the first time. By

the way,

Hvorostovsky sang

his first Iago with

me.

Q: Speaking generally, do you

think that the

nationality or the

opera school has a

great influence on

the singer, on his

manner of singing?

JC: Singing is a

cultural phenomenon,

as is painting,

literature or

dance. One does not

just click the

button and start to

sing. In this

sense, the

Argentinian will not

sing like an

Italian, the Italian

will not sing like a

Frenchman, and the

Frenchman will not

sing like Russian.

Each of us,

expressing ourselves

in art, does this

through the cultural

baggage that is in

his head and often

in the heart. Of

course, training can

help, but if

everyone could sing

like an Italian in

an Italian opera,

like a German in a

German opera, like

Russian in Russian -

that would be

perfect, but it's

very difficult.

That's why, for

example, I do not

sing Russian opera.

I do not have a base

on which I could

feel myself as

Russian. I would

just copy as a

pirate. If they

offered Herman for

me to sing, it would

not be me singing

Herman, but it would

be me mimicking

someone who sang

Herman, because I do

not have the

knowledge of either

the Russian language

or Russian culture.

For the same reason,

I do not sing a

German opera. I

sing Italian,

French, English,

Spanish opera,

because I know these

languages and

understand the

culture. I think

that it is very

important for an

artist to be honest

in this matter,

including

recognizing that in

this honesty the

difference between

the artist and the

performer is

manifested. Every

artist is a

performer, but not

every performer is

an artist.

Q: In Russia, only 4-5 of the 40

opera houses are

widely known. Is it

the same in

Argentina? Are

there any well-known

theaters besides the

Colón Theater in

Buenos Aires? Is

there anything

interesting in them?

JC: This is not an

easy question. Why

does fame appear?

First of all, the

place, in our case

the theater, should

be part of the

story--for example,

if there were

high-profile

premieres in the

theater. It is also

a matter of economic

power-- that is,

money—and whether

the theater can

launch a "media

machine" and make

people talk about

it. That is, it

turns out that this

is not a question of

what we like but a

question of what

moves the business.

We are engaged in

business related to

beautiful things,

but it's still

business.

The Mariinsky is

known for many

premieres, the same

can be said about La

Scala and others.

There are positive

and negative points

in this, depending

on perspective. If

the theater works,

it has its own

audience, its

sponsors and it

plays an important

social role in the

city. And then it's

not really important

if it is a famous

theater or not.

Fame is very

ephemeral, today you

have it, tomorrow

you do not. It is

important not just

to be known, but to

be useful to the

environment in which

you are in. I would

even put the

question

differently. Many

famous theaters are

known today only

because of their

past. They do not

serve the present,

they do nothing to

be known in the

present. Of course,

I will not mention

names. But it's one

thing to be in the

halo of the glory of

your predecessors

and it's another

thing to work for

the glory of your

present. Therefore,

the question you

asked me is not so

easy to answer.

Q: Then let me ask this a little

differently. If I

come to Argentina,

which theater should

I visit besides the

Colón?

JC: If you come to

Argentina and

visited the Teatro

Colón and a few more

theaters, I can only

say: what a pity!

Of course, the Colón

Theater is

incredibly good, and

the artists of the

Colón Theater are

some of the best in

the world, but if

you want to come to

Argentina just for

the sake of it

alone, then do not

come at all because

you can find about

the same thing in

any famous theater

in Europe. Arriving

in Argentina, you

need to visit a lot,

including the

Colón. Argentina is

an incredibly

beautiful country,

maybe one of the

most beautiful on

earth, but, as often

happens, people come

to the country and

visit one or two of

the most famous and

large cities: Moscow

and St. Petersburg

in Russia,

Washington and New

York in the US, Rome

and Milan in Italy.

But the real beauty

of the country is

often not in the

capital.

Q: You just do not want to name

names, so I'll ask a

general question.

You are a dramatic

tenor, the owner of

a rare type of

voice. Since there

are not many

dramatic tenors,

other tenors are

forced to play

dramatic roles. Is

it really dangerous

to sing something

that is not meant

for your type of

voice?

JC: I will answer

with an abstract

example, because if

I answer using

technical terms, it

will not be

completely clear.

Imagine a boxer

weighing 50 kg. If

he competes with

another 50 kg boxer,

then everything is

in order. If he is

in the weight

category 50 - 60 kg,

this is also

normal. But if he

enters into a fight

with a 100-kilogram

opponent, then

obviously he plans

to die. Opera is

the same. Otello is

a heavy role, Canio

is a heavy role,

Grimes is also a

100-kilogram role

but if you are a 100

kg boxer, you can

deal with them.

Nobody says it's

easy, but it's

physically

possible. But if

you are 50 kg and

you're going to

fight Mike Tyson,

you can say with

certainty that you

will lose.

Q: Please tell us about Peter

Grimes. You sang

the lead role and

directed this opera

at the same time.

How hard is it to

sing in your own

production?

JC: I must say that

for me it was an

incredible

pleasure. Again I

do not want to talk

using technical

terms, because then

I will remain

someone not

understood. I will

explain with another

example. Imagine

yourself writing a

book where you can

open a page and step

into it, become one

of its characters,

or paint a picture

and by magic can

enter your

creation. This is

the feeling that you

have when

participating in

your own

production. You

seem to have stepped

into your dream.

This is the romantic

side. The

unromantic side is

that it is very

difficult. If you

are a singer, then

you have a rehearsal

of 3 hours or a dual

rehearsal of 6

hours, and then you

go home. If you are

a producer, then you

have meetings with

technicians,

engineers, lighting,

then rehearsals with

singers, rehearsals

with the orchestra,

pianists, and then

everything in a new

circle. When I put

on a performance,

I'm at the theater

from 8.30 to 23.00

every day.

Q: You brought a remarkable

comparison "step

into your dream" ...

JC: Yes, often

people think only

about the negative

side but not to

remember the

positive. Imagine,

you can live your

dream! You can

create the world you

dreamed of and step

into it and live in

it. Some people

criticize me but

then I ask: "And

what would you do in

my place?" And they

reply: "You are

right, I would do

the same." Of

course! They would

have done it if they

had had a chance.

Someone may disagree

with the fact that I

do several things at

once but for me it's

more important how I

do it, whether the

singers and the

orchestra are good,

whether the

production is

interesting. And if

the answer is "yes,

it's done well, it's

done professionally"

- then what's the

problem? For me,

that is the only

thing that matters.

And it's also

important that the

people you work with

work well. You deal

with real people,

the motor of the

theater, the heart

of the theater. The

heart of the theater

is not the

quartermaster, not

the administration,

not the soloists,

not the musical

director, they can

change. The heart

of the theater is

technicians,

electricians,

chorus, orchestra,

these guys are

always here. They

are the theater's

blood. And if these

people are happy to

work with you, if

they are proud to

work with you and,

most importantly, if

they feel safe

working with you,

then you are doing

everything right.

Then people can like

what you do or not

like it, but no one

will say that you

did it

unprofessionally.

This is a border

that I will not

cross. If I am

offered the chance

to do something and

I know that I am not

able to do it

professionally, I

will say no. But if

I can do it on a

professional level,

even if it's

terribly difficult,

I'll do it. And I

will do it even

knowing that I can

be criticized.

Because life is

short. And if you

live all the time,

looking around,

thinking only about

others will say,

then you live a

shitty life. We

cannot change a

short life. But a

shitty life, we

probably have the

power to change

that. And this is

our own decision.

Q: What would you advise young

singers for career

development? Is it

better to stay in

home and make a

career at the

theater and then go

out to conquer the

world’s opera scene,

or to head out into

the world at the

beginning of a

professional career

and starting with

small

roles?

JC: There is no

answer to this

question. We need to

place ourselves in

the perspective of

the present and see

what kind of world

we live in now. Both

opera and classical

art are not outside

this world, they are

part of it. They are

part of a big

machine, part of

society. We live in

a very difficult

time: terrorism,

immigration,

environmental

pollution, crazy

guys from North

Korea, experimenting

with a nuclear bomb

and so on. In

addition, the large

unemployment among

young people is, in

fact, a great social

drama. In this

reality, it is

unrealistic to worry

too much about the

future of classical

art. This does not

mean that we should

not do this! This

means that we must

persist , because

beauty (and what we

do is beauty) is

always food for the

soul, and we should

not stop! And I will

be the first to

insist that we

should not stop. If

the social machine

does not provide it,

then the person will

seek for beauty

himself because he

needs it. And

looking for beauty,

you will find it in

nature, you will

find it in God, if

you believe in God,

you will find it in

music, ballet,

painting, anywhere.

But it's pointless

to ask society to

take care of the

opera, when most

people think about

how to hold out

until the end of the

month.

What can I advise

the young? I do not

know. The world now

and the world when I

started 30 years ago

are very different.

It is difficult to

give advice you are

sure will be good

advice in 90% of

cases. How to tell

young artists "work

hard, learn a lot

and you will achieve

something" when

young artists watch

TV and see that

someone, just by

having a "Big

Brother" can become

a popular artist?

How can you explain

to your child that

someone, without

making any effort,

can become

successful and

famous? It is

difficult to find an

answer to this. My

son is a movie actor

and we often talk

about it. How can

you explain why you

need to study for 10

years at the academy

when some model or

football player or

rock musician

becomes an actor and

gets a role simply

because he is known?

But I do not want

young people to lose

hope, lose the

desire to make

efforts, so they

think "if it's just

this way, I will not

make it anyway,"

because it is not

true. It happens.

And if you really

try, maybe it will

happen. Even in the

past there was never

a formula for

success. Now it’s

just more difficult.

There is no single

formula for true

success. To become

famous now appear in

the news in any way

and you will

automatically become

famous. I can give

interviews in front

of the camera and

someone will push or

insult me and it

will be shown on the

news and it will

instantly become

known. With the

media this is very

simple. So today the

bigger task is not

to become famous but

to become

outstanding in your

career. Therefore,

my advice to young

people, to young

artists: do not seek

fame, because fame

is short and

ephemeral. Strive

for greatness in

work and in life.

* The interview was taken from

Jose Cura in his

previous visit to

St. Petersburg

(10/28/2017)

|

.jpg)

.jpg)