|

In

Search of the Real Samson and Dalila

from Lyric Opera News

Winter 2003/2004

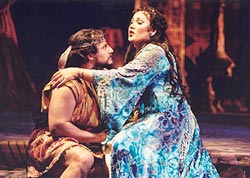

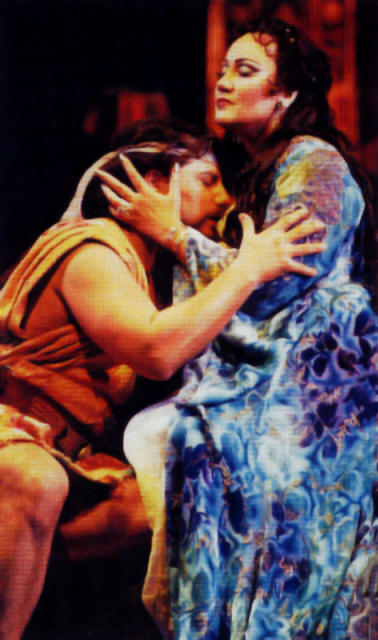

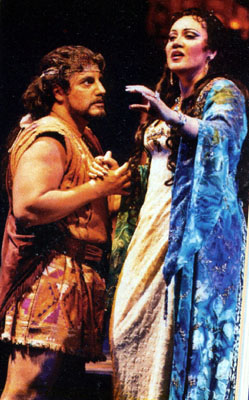

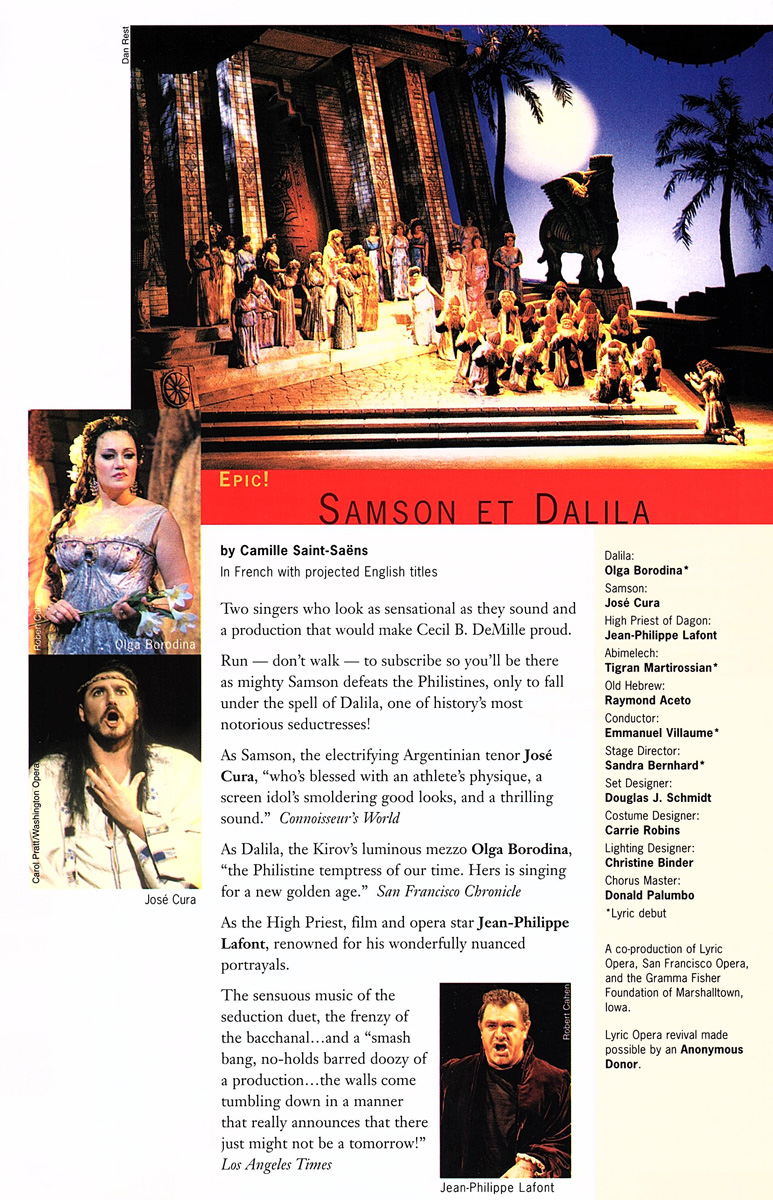

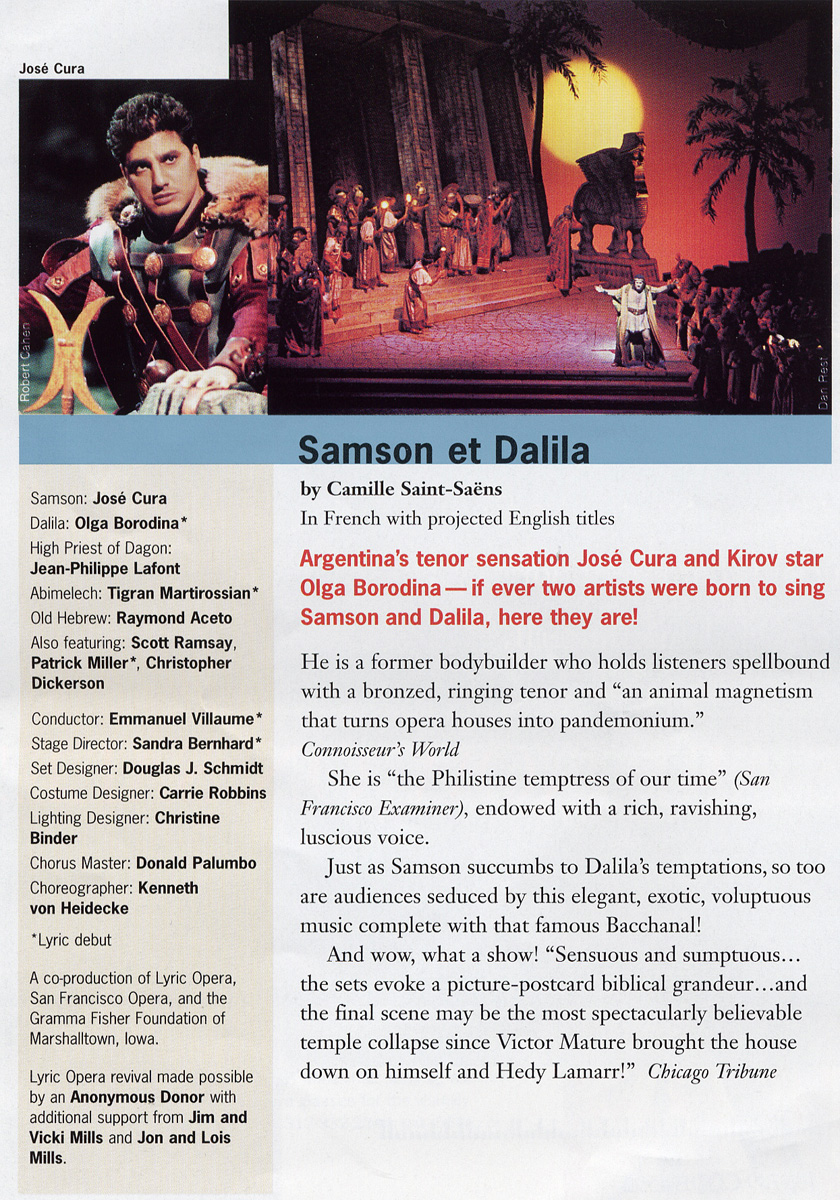

“Samson

et Dalila is certainly sexier than any opera written

before it,” declares Russian mezzo-soprano Olga Borodina,

the star of St. Petersburg’s Kirov Opera, who will sing

Dalila in her Lyric debut.

In

its initial stages however, Samson et Dalila was

neither sexy now an opera. It was 1867 when Camille

Saint-Saëns started working on his Samson

oratorio. After hearing it performed, Franz Liszt

suggested his colleague rethink it as an opera. There

was one problem, though: in France, prevailing attitudes

of the time prevented biblical scenes being portrayed on

the stage, even in liberal Paris. As a result,

Samson et Dalila (opera in three acts, libretto by

Ferdinand Lemaire), premiered on Dec. 2, 1877, in

Weimar, Germany. It was not staged in France until 13

years after its Weimar premiere.

For much of the 20th century, audiences

considered Samson et Dalila to be old-fashioned,

but that is no longer the case. “The audience nowadays

accepts conventions that were diff icult to accept during

the 20th century,” says conductor Emmanuel

Villaume, who will lead Lyric’s Samson in his

company debut. “Sometimes pure beauty of the vocal line

and clarity were equated with a lack of depth, but today

people are beyond this,” Indeed they are. Modern

audiences agree with those of the 19th

century: Samson et Dalila contains some of the

most beautiful music every written for the opera house,

including one of the most famous and most seductive

arias in all opera, “Mon Coeur s’ouvre a ta voix.” In

addition to gorgeous arias, the opera also offers a

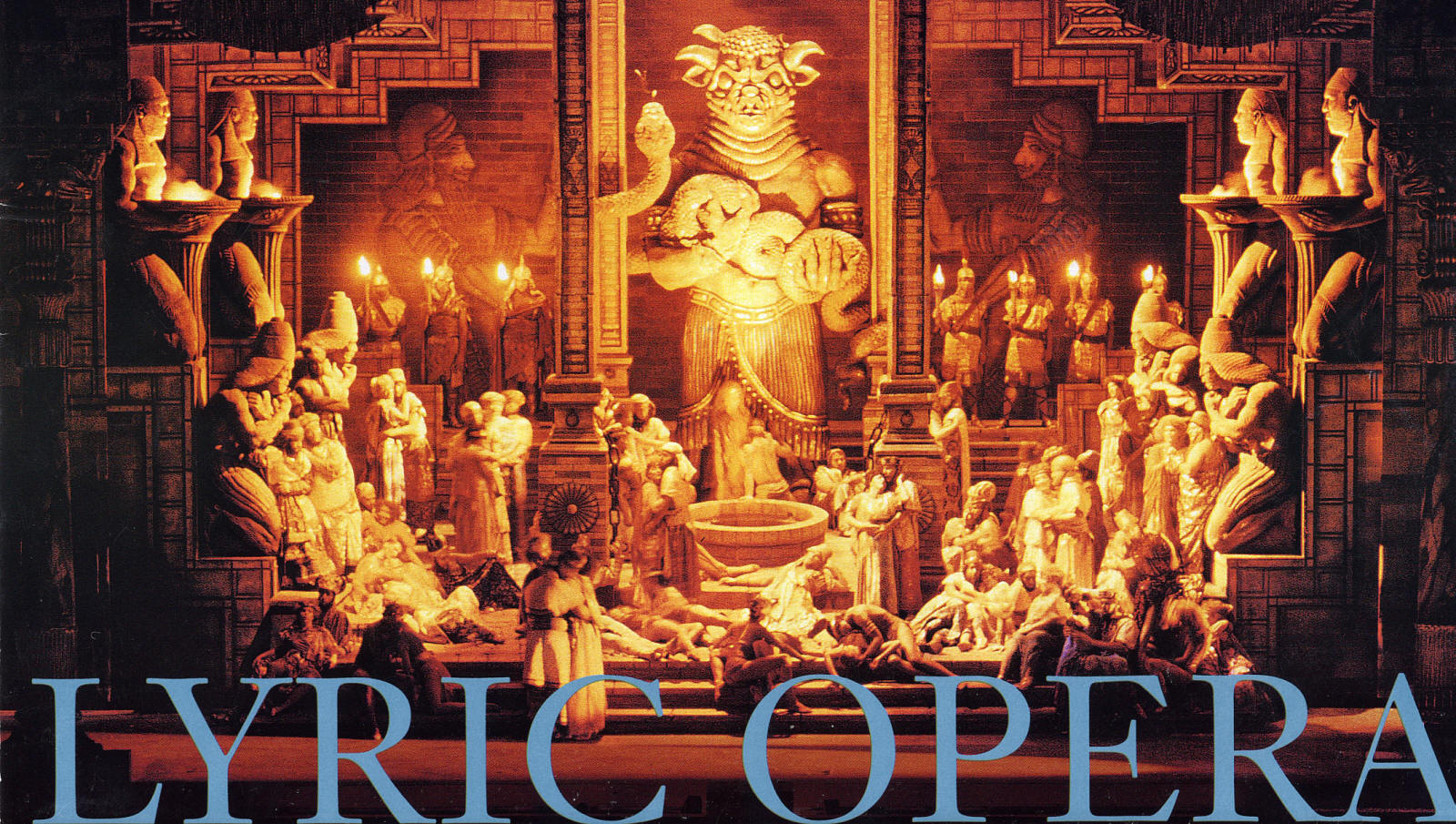

temperature-raising, semi-orgiastic bacchanal scene

which shows that if nothing else, those Philistines knew

how to party! icult to accept during

the 20th century,” says conductor Emmanuel

Villaume, who will lead Lyric’s Samson in his

company debut. “Sometimes pure beauty of the vocal line

and clarity were equated with a lack of depth, but today

people are beyond this,” Indeed they are. Modern

audiences agree with those of the 19th

century: Samson et Dalila contains some of the

most beautiful music every written for the opera house,

including one of the most famous and most seductive

arias in all opera, “Mon Coeur s’ouvre a ta voix.” In

addition to gorgeous arias, the opera also offers a

temperature-raising, semi-orgiastic bacchanal scene

which shows that if nothing else, those Philistines knew

how to party!

In

keeping with its oratorio beginnings,

Saint-Saëns’s opera contains choruses which, as

Villaume points out, “are not exactly involved in the

development of the action, but rather a commentary on

the action.” While the confrontational scenes between

Samson and Dalila are quite dramatic, Villaume thinks

there is a different purpose for their presence: “They

are a way for the composer’s musicality to express

itself. Ultimately what Saint Saëns is going for is a

score of great musical power, color, and balance, but I

don’t think he is going for pure dramatic effect. He’s

always staying a musician. He’s using the power of the

story to express something and to portray something

which is first of all a musical idea.”

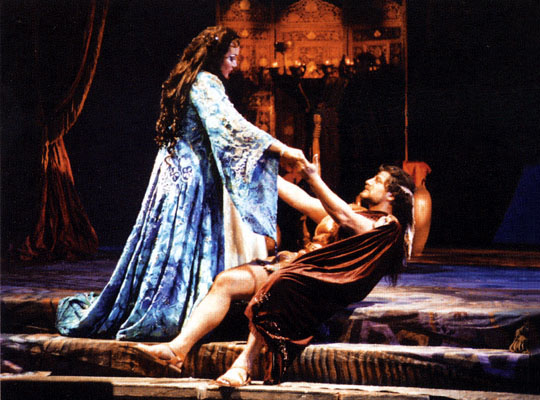

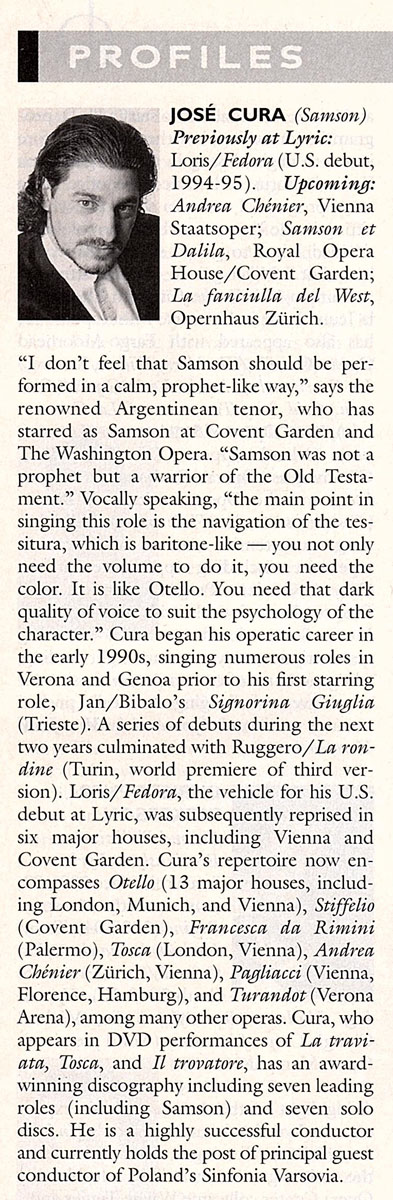

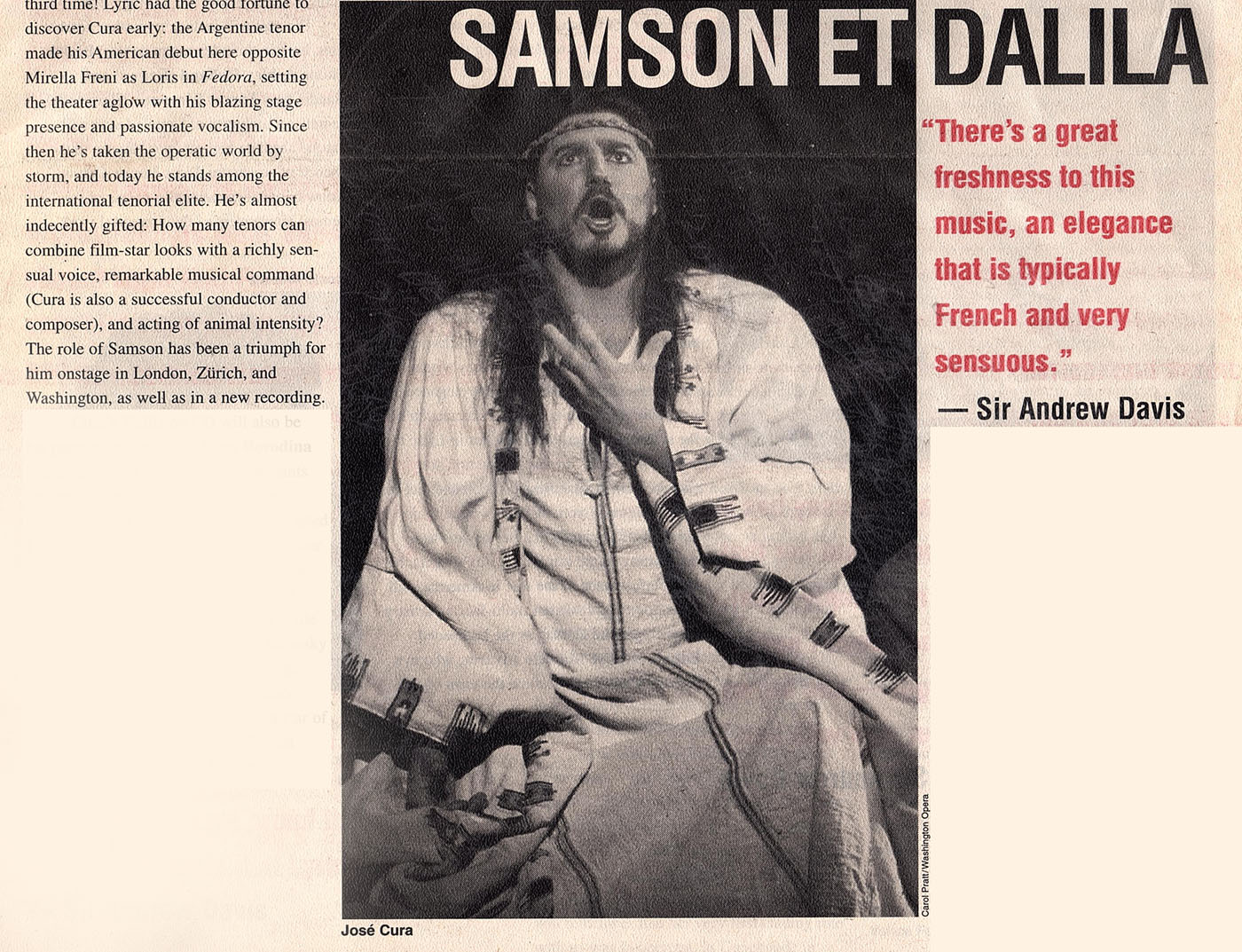

Even though the work started out as an oratorio, it

contains plenty of drama – especially in this

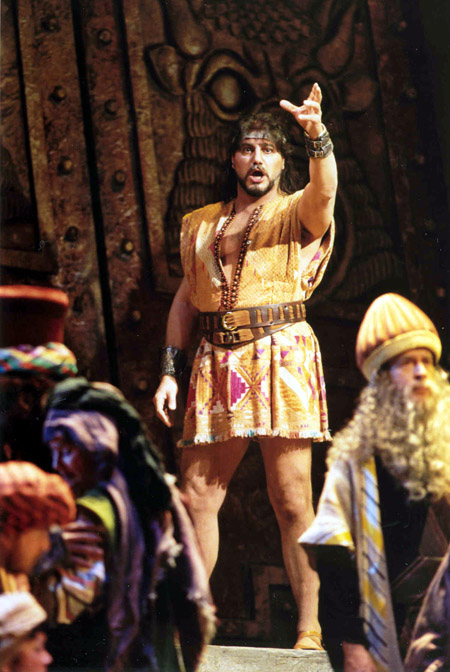

production, with José Cura playing Samson. “If I were

to portray Samson as a nice, sweet character, an Old

Testament prophet, I would not be portraying the real

Samson,” he says.

Do

not think that José Cura could ever be less than real:

“The Argentinian tenor gives to Samson all the strength

of his magnetic presence, all the energy of a vocal

emission of unseen arrogance,” wrote Sergio Segalini of

Opera International. “Cura confirms himself to

be the only possibly imaginable performer for Samson

since Jon Vickers’s retirement.”

Indeed, the “Samson of our times” has strong feelings

about the role. “Samson was not a prophet but a

warrior,” Cura says. “To put it in modern terminology,

Samson could be an Old-Testament terrorist, who believed

in killing anyone who didn’t think the way he did.”

At

least, that is how Cura sees Samson in the first two

acts. “In Act One he is an Old-Testament Che Guevara.

In the second act we see that Samson completely

misunderstands the spiritual meaning of his life. He

was of the flesh – a man filled with animalistic

adrenalin – and that is why he was so easily corrupted.”

But was he corrupted, or did he simply surrender to

Dalila’s love? Borodina thinks Dalila is something more

than a biblical femme fatal. “My Dalila loves

Samson very much,” she says. “But Dalila is a patriot

and she remembers her duty.” The libretto shows this

dichotomy: “Love come to my aid . . . Fill his heart

with your poison,” Dalila sings. “A god much greater

than your speaks through me – my god, the god of love.”

(Borodina spoke to Lyric Opera News by phone

during a family vacation at her dacha in the

Russian countryside.)

Once Samson surrenders to Dalila he becomes powerless,

is blinded by his captors, and winds up doing slave

labor. He begs his people to forgive him and begs God

for the return of his strength. Not surprisingly, when

his strength is miraculously restored, Samson uses it to

kill the Philistines by pulling down the temple. (If

the story sounds like a Cecil B. DeMille

sword-and-scandal epic, it is! DeMille directed the

1949 movie Samson and Delilah starring Victor

Mature and Hedy Lamarr.)

Cura sees something more to the story than a strong man,

a sexy woman, and tumbling pillars. “Samson completely

misunderstood his gift of strength,” he says. “He

thought his strength was given to him so he could

destroy anyone who didn’t agree with him. He may have

thought he was very spiritual, but he was not. He

reduced everything to simply killing and taking. The

real Samson, and I mean ‘real’ in the sense of the

spiritual character, is seen early in the third act when

he begs his people for forgiveness for what he has

done. It is there that he finally sees his real

mission, which of course leaves us suspended in

conflicting thoughts. Samson becomes very spiritual in

asking God to give his back his strength, but when he

gets it, he pulls the temple down killing everyone.

Today solving problems through war and aggression is

something that is seen on every TV newscast. The story

of Samson is not that old-fashioned after all. In

Samson’s time strength was in muscles – today it is in

bombs.”

To

Cura, having a certain quality of voice is absolutely

essential for Samson. Despite that fact that the

character is a tough, primitive kind of guy, a good deal

of subtlety is needed to portray him, and while “might

makes right” in the biblical story, there is much more

than raw power needed for this role. “You can sing very

loud, but if you do not sing deep and dark and accent

the proper words, then the whole psychological impact of

Samson gets lost.” Cura says. “It is the same in

Otello. It is not about singing loud but singing

with just the right color. It is one thing to sing all

the notes with great volume, but if you don’t have the

proper color, then you lose that extra ingredient that

makes the character believable.”

|

While in Chicago....

Super-Tenor

Shines on Bloomington

22 January 2004

Eric Anderson

Indiana Daily Student

|

The events of José Cura's still-blossoming opera

career have already become the stuff of legend:

He learned the role of Ruggero for Puccini's 'La

Rondine' while performing in Verdi's 'La Forza del

Destino' by attending 'Rondine' staging rehearsals

in the basement of the opera house during the second

act of 'Forza,' when his character was not present

on stage.

In 1999, he made history at the Metropolitan Opera

as only the second tenor in the company's history to

debut on opening night (the first being the grandest

of all tenors, Enrico Caruso, in 1902).

Just a year ago, he further cemented himself into

music mythology by first conducting Muscagni's

one-act opera 'Cavelleria Rusticana' at the

Hamburgische Staatsoper, then mounting the stage

after intermission to perform the role of Canio in

'Pagliacci.'

The School of Music had the good fortune to catch

this growing titan of the opera world between

performances for a special guest lecture and

masterclass.

His lecture, "Singer, Musician…Antonyms?", attracted

a large and attentive crowd to Auer Concert Hall

Sunday night, where Cura spoke for nearly two hours

over the beginnings, triumphs and frustrations from

his extensive career as a professional musician.

Seated on the edge of the stage, dressed in a black

sweater and blue jeans, Cura gazed at the seats

directly in front of him.

"Do you know how I feel coming out here to speak,

only to find the first two rows empty," he asked in

his strong Argentinean accent. "I refuse to start

until you all move up and fill in the front rows.

"You," he called to those in the balcony, "come down

here, the ticket price is the same!"

Cura began the lecture with an interesting question.

"How does the world regard tenors?" he asked. "Like

a piece of shouting meat."

For the next hour and a half, Cura was part

autobiographer, part philosopher, his penchant for

storytelling never failing to deliver a comic

anecdote or pearl of professional wisdom.

"Study, work, bloody your fingers," Cura said.

"That's the best luck in the world."

Proclaimed by many to be "a true renaissance man,"

the tenor certainly does not fall easily into any

category.

Though he is now famous for his interpretations of

the great tenor roles -- among them Verdi's Otello

and Saint-Saëns' Samson, which he is currently

performing at the Chicago Lyric Opera -- Cura

actually began his musical studies with no

aspiration to professional singing.

His first piano teacher rejected him for having, in

Cura's own words, "no gift for music," and so he

decided instead to study the guitar.

Ernesto Bitetti, a professor of guitar at the School

of Music was instrumental in arranging Cura's visit

and has been a long-term friend of the Cura family.

He said he remembers young José in his pursuit of

guitar mastery.

"I've known him since he was 14 ... he was a very

talented guitarist," Bitetti said. "Now, of course,

he is better at his singing."

In fact, Cura was apparently so taken with the

instrument he wrote a letter to the IU School of

Music expressing interest in completing a guitar

major at the Bloomington campus. (He was,

unfortunately, rejected, as the school did not yet

have a guitar performance program.)

Cura was soon studying conducting and composition

and in 1991, at the insistence of a university

choirmaster, departed for Europe to pursue a

professional career in voice. The rest, as they say,

is history.

For all his worldly experience and artistic

expertise, Cura displays a remarkable ease with the

students around him.

Tenor Emilio Pons, who was the first to sing in

Monday morning's masterclass, was chastised by Cura

for spending "half the aria deciding whether you

were nervous or not."

Cura encouraged Pons to overcome his nerves by

drawing a parallel to performing Verdi's 'Aida.'

"When you open 'Aida,' [it's so difficult] you think

'f-k you, Verdi,'" he said, eliciting laughter from

the audience gathered in Sweeney lecture hall.

"People ask me what technique I use [to

prepare]…there is only one technique," Cura said.

"Balls."

"[Cura] is very comfortable," said tenor Eduardo

Gracia, who also sang for him that day. "He

transmits calm."

His easy, straightforward and always diligent manner

revealed itself again while Cura coached soprano

Carelle Flores in interpreting the text of her

Puccini aria.

"Have you ever been kissed?" he asked her directly.

"Was it a revelation of passion?

"Come on," he said, responding to her embarrassed

laughter, "haven't you ever made love? Of course

not…you are all nuns here."

It is hard to believe that this man, himself so full

of passion, still encounters more than his share of

resistance in the music industry.

Toward the end of the 1990s, tired of his played-up

image as the sex-symbol of opera, Cura declined to

renew his contracts with both his agent and

recording label. Now, there are opera houses that

find it too politically unsavory to engage him. His

CDs are harder to find. And yet, he has found a

greater peace as a free agent opera star.

"Now," he said, "I look in the mirror every morning

and I am happy. I only go to sing where people want

me to sing ... they're not there because they were

invited.

"Plus," he added, "I have contracts until 2010, so I

can't complain."

And his audience certainly had no complaints either.

"Spectacular" was the word of choice for Marianne

Kielian-Gilbert, a theory professor.

"You never see this [kind of event]," she said.

"This is right where it should be happening."

Cura concluded Monday's class by performing his

final scene from Verdi's 'Otello' -- a scene that

has garnered him both praise and criticism for his

exceptionally theatrical interpretation.

Cura has brought an extensive amount of research and

analysis to the role, not to mention a deep dramatic

commitment -- and all were evident to the audience

as he played out the suicide of Otello with such

abandon as to suggest he had mistaken Sweeney Hall

for the Teatro alla Scala.

Having heaved Otello's final breath, Cura looked up

from the floor where he knelt, breathless from his

exertion, and whispered: "If I continue singing for

20 years, it will be like this."

His audience, myself included, certainly hopes so.

|

|

José Cura offers master class worth cheering about

25 January 2004

Peter Jacobi

Herald Times

|

World-class tenor José Cura made a Sunday-Monday

stop in Bloomington this past week and proved that,

despite opinions some in the realm of music cling

to, a tenor is not "a piece of shouting meat" and

that Maria Callas was generalizing when she referred

to that category of singers as "beasts."

Quite

the contrary, the seemingly genial, relaxed Cura,

dressed for both a lecture and master class in jeans

and loose-hanging collarless top, made quite an

impression as a generous and sagacious gentleman,

both ready to and capable of giving very good

advice.

He was

here thanks to Ernesto Bitetti, the head of guitar

studies in the IU School of Music, and the Lyric

Opera of Chicago. To explain: Bitetti has been a

long-time family friend, one who, when the tenor was

a boy in his native

Argentina

encouraged him to take up music. The Lyric Opera is

Cura's current artistic home; he's appearing there

in Samson et Dalila as the hero with the long hair

who falls for the wiles of the scheming woman who

shares the opera's title.

Bitetti

suggested that as long as he was in the area, why

not drop down to

Bloomington

and give

the voice students some sage counsel. Cura agreed,

his interest fed also by the fact that more than 20

years ago, when he yearned to become a guitarist, he

wrote to the music school seeking admission, only to

be told that no degree in guitar performance was

available, only a few courses. Cura turned to other

avenues and other places.

On

Sunday evening in Auer Hall, he spoke about those

other avenues and places. The guitar, though he

loved it deeply and still does, was not to be his

musical specialty. He discovered that he simply

wasn't good enough. Instead, he turned to choral

conducting and to composition and, finally, to

singing. "There were disappointments along the way,"

he said. "When I was seven, my father sent me to a

piano teacher. 'No gift,' the teacher told him. I

decided on rugby and built my muscles. A friend told

me to play the guitar to be more successful with the

girls."

And so

went visitor Cura's account, through twisting roads

of study and shifting career goals (although

determination to make music his life never

faltered), through marriage and children and

financial crises. "I didn't want to be a singer,

really. Now conducting, ah! But the best advice came

from a teacher who said, 'You have to study singing.

It's the only way you'll become a conductor.' And so

I did. And look what happened. But if someone comes

to me to offer a job as conductor, I'll quit

singing."

Cura's

audience was bulging with voice students. "What's in

your heart?" he urged them to ask themselves. "How

do you see yourself in 10 years? This business is a

jungle. You have to have a goal." He admitted to

luck being a factor to have his level of success.

"The train passes once, maybe twice, and you must be

ready to catch it or be left in the desert. But it's

mostly study and work."

Cura's

lecture was extemporaneous, definitely low-keyed.

His Monday master class in Sweeney Hall was charged

with electricity and was, for the three young

singers who performed for him and for those who came

to listen and learn, a concentrated lesson on

matters of interpretation, vocal control and

performance practice. Here he proved the master.

For two

hours, he listened and he taught. He advised. He

demonstrated. He amazed.

The

hours were rich with words worth remembering:

· "You

cannot be a musician in less than 10 years. And

then, 10 years more. Twenty years. Think of that.

Who is willing to do that today? Nowadays, we push

buttons to get quick solutions. You ask, why a

dearth of voices? That's why."

·

"You've broken the ice," he told the morning's first

singer. "That's one of the hardest things to do.

With your voice and courage, you'll go far. ... Now,

sing the aria again. You spent half of it trying to

decide whether to be nervous or not."

· "Put

your hands in your pocket. Act with your voice.

Overuse your hands, and when the time comes for

hands, no impact is left. Simplify your action."

· "Work

in front of a mirror. Don't let your face show the

tremendous struggle inside. That makes the viewer

uncomfortable."

·

"Don't ever let a pianist or conductor push you.

Take time to breathe, then move ahead. And don't

leave a note until you get from that note the best

sound possible."

· "I

can see you're nervous. You'll hurt your voice if

you try the next note," he told a soprano,

attempting for the minutes that followed to calm her

down. She did.

· "Sing

for you. A natural on stage never acts for the

audience. You portray a character. Show that you're

a mature woman falling for a younger man. Sing to my

eyes."

·

"You're very angry," Cura reminded a tenor after

completing a recitative to a Verdi aria. "Convince

me of that without overacting."

·

"Create the feel of something happening, that what

you're singing is immediate, not planned."

·

"Verdi was the genius. We are not. Our job is to be

expressive of what he wrote."

To prove

that last point, Cura devoted the final 30 minutes

of his session to explaining, then singing the death

scene from Verdi's Otello. He spoke of learning how

to die on stage without being ridiculous.

"Sometimes," he said, "you die for a whole act.

There's an edge between what's interesting and

believable and what is ridiculous. A thin edge." He

said he consulted a doctor, "If I stabbed myself,

would I die immediately? Would I bleed? Would I

suffer? If you stab yourself in the stomach, it

takes ages to die. When you remove your knife, you

really die. You see, it's up to us to find out how

Violetta or Mimi dies, how Riccardo dies for 20

minutes in A Masked Ball. The baritone has to stab

him the right way. And Otello does. He's a man of

weapons, and he knows."

Cura

discussed motivations that resulted in Otello's easy

fall to Iago's duplicity, the self-loathing, he

said, of a Muslim who has led Christian forces to

defeat his own people, a mercenary who feels

undeserving of Desdemona. "My Otello is not heroic,"

Cura explained. "He is a betrayer and hypocritical.

He sees that in those around him. Under that

psychological pressure, even a handkerchief can have

power. Alone, by himself, Otello is too cowardly to

destroy himself. He waits for someone else to do it

for him. At the end, he decides to be a Muslim

again. He can kill his wife. Because he loves her,

he suffocates her with a kiss and hands. He then

realizes what he has done and kills himself as a

supreme act of cowardice," choosing not to face

death from others who might want to punish him.

Using a prone woman student as the dead Desdemona,

Cura proceeded to act out and sing that death scene

with such passion and persuasiveness that this

listener came to tears and the audience gave him an

extended and cheer-filled ovation.

José

Cura had left advice and a strong impression.

Outstanding tenor, yes, but outstanding musician,

too. He had titled his lecture, "Singer and

Musician, Antonyms?" In his case, synonyms.

|

|

|

icult to accept during

the 20th century,” says conductor Emmanuel

Villaume, who will lead Lyric’s Samson in his

company debut. “Sometimes pure beauty of the vocal line

and clarity were equated with a lack of depth, but today

people are beyond this,” Indeed they are. Modern

audiences agree with those of the 19th

century: Samson et Dalila contains some of the

most beautiful music every written for the opera house,

including one of the most famous and most seductive

arias in all opera, “Mon Coeur s’ouvre a ta voix.” In

addition to gorgeous arias, the opera also offers a

temperature-raising, semi-orgiastic bacchanal scene

which shows that if nothing else, those Philistines knew

how to party!

icult to accept during

the 20th century,” says conductor Emmanuel

Villaume, who will lead Lyric’s Samson in his

company debut. “Sometimes pure beauty of the vocal line

and clarity were equated with a lack of depth, but today

people are beyond this,” Indeed they are. Modern

audiences agree with those of the 19th

century: Samson et Dalila contains some of the

most beautiful music every written for the opera house,

including one of the most famous and most seductive

arias in all opera, “Mon Coeur s’ouvre a ta voix.” In

addition to gorgeous arias, the opera also offers a

temperature-raising, semi-orgiastic bacchanal scene

which shows that if nothing else, those Philistines knew

how to party!

Critical

opinion of Saint-Saens’s one

hit, Samson et Dalila,

often veer toward

self-conscious

patronization, as though

learned men were embarrassed

to admit they really like

it. In truth, the opera is

hardly a masterpiece. A

certain dramatic rigidity,

particularly in Act 1,

betrays the work’s original

oratorio concept, and design

excess has tended to render

it as glitzy, quasi-Biblical

kitsch. However, when

Samson et Dalila is as

intelligently produced as it

was in Lyric Opera of

Chicago’s stunning revival

(seen Dec. 18), it can be a

terrific night at the opera.

Critical

opinion of Saint-Saens’s one

hit, Samson et Dalila,

often veer toward

self-conscious

patronization, as though

learned men were embarrassed

to admit they really like

it. In truth, the opera is

hardly a masterpiece. A

certain dramatic rigidity,

particularly in Act 1,

betrays the work’s original

oratorio concept, and design

excess has tended to render

it as glitzy, quasi-Biblical

kitsch. However, when

Samson et Dalila is as

intelligently produced as it

was in Lyric Opera of

Chicago’s stunning revival

(seen Dec. 18), it can be a

terrific night at the opera.