“Filling Out the Frock Coat”

“Stiffelio” by Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901).

The Metropolitan Opera, Saturday 23 January 2010, 8PM

[Excerpts]

Bravo Cura

Celebrating José Cura--Singer, Conductor, Director

Retrospectives

|

|

Cura gets a VERY Special Award Kammersänger

|

|

|

||

|

|

José Cura: In Concert – Budapest 2000

Vocal works by Puccini, Verdi, Leoncavallo, Cilèa

Reviewed by BBC Music

Michael Scott Rohan

4 Stars

José Cura undoubtedly has many ideal qualifications as a star tenor—an arresting Italianate spinto voice with a ringing top and usefully dark lower register; stocky good looks, and no shortage of boyish charisma. He has an enviable international career, including notable Covent Garden appearances in Fanciulla del West and Stiffelio, and sometimes conducts, as in the Manon Lescaut and Forza del destino intermezzos here. But while there’s plenty here to please in this concert from earlier in his career, there’s also some suggestion why he hasn’t quite achieved the heights of Domingo or Carreras status.

A 2000 television taping from Budapest’s unlovely Erkel Theater, this disc has a slightly bargain-basement feel. However, the orchestra and conductor are decent enough, and Cura features some less usual arias, from Puccini’s early, problematical Edgar and Leoncavallo’s Bohème. He prowls the platform, sings with a fervor which excites his audience to frenzies; he plays them charmingly, even pinching the conductor’s baton for one in the front row. But in recording one notices more clearly how that rich tone sometimes coarsens, and his foursquare phrasing, for example in ‘Ch’ella mi creda’ or ‘E lucevan le stella.’ Pinkerton and Alfredo are too heavy and inelegant; he’s most convincing letting it all hang out as Macduff and in ‘Nessun dorma’.

|

Stiffelio @ the Met, Jan 2010

|

|

Wife’s Betrayal, a Husband’s Internal Struggle

Anthony Tommasini

January 12, 2010

New York Times

[Excerpts]

In 1993 the Metropolitan Opera presented its first production of Verdi’s neglected opera “Stiffelio” as a vehicle for Plácido Domingo. Without that star tenor in the demanding title role, and without James Levine conducting, the Met would not have taken a risk on the work, which had a dismal reception at its 1850 premiere in Trieste, Italy.

The risk paid off. Performed in a critical edition that incorporated newly discovered parts of the autograph manuscript, “Stiffelio” was revealed as a realistic human drama about an evangelical minister in mid-19th-century Austria, facing a spiritual crisis after his wife’s infidelity. If the music is not at the inspired level of the operas that immediately followed it (“Rigoletto,” “Il Trovatore” and “La Traviata”), the score offers first-rate Verdi. The production, a realistic, handsome but unexceptional staging by Giancarlo del Monaco, broadcast on public television, offered Mr. Domingo in his prime.

Mr. Domingo was back on Monday night for the revival of “Stiffelio,” last seen at the Met in 1998. But this time he was in the pit, conducting. Stiffelio was the Argentine tenor José Cura, who actually began his career as a conductor. While Mr. Cura, an enormously gifted artist, has a loyal fan base, his singing can be erratic and has been variously received in recent years. Over all, he had a good night.

Mr. Domingo’s conducting has also been a source of great debate. He is no match for the other Verdi conductors that the Met will be presenting in the next two months: Mr. Levine in “Simon Boccanegra” and Riccardo Muti in “Attila.” If anything, Mr. Domingo was deferential to the singers to the point that the music lost energy, focus and drive. Occasionally there were hesitant moments of ensemble and shaky entrances.

“Stiffelio” is a drama of internalized conflicts and emotion. Mr. Cura has made his name with vocally raw, vehement portrayals of hotheads, especially Otello and Samson. Here he tried to convey the solemnity of this minister, seething inside over his wife’s betrayal. In bringing restraint and finesse to his singing, he sometimes let the energy drain away. At its best, his performance had flashes of vocal charisma. Still, I wish he had made more of the vocal and emotional similarities between this role and Otello.

Ms. Radvanovsky again proved herself a compelling Verdi soprano. She sang with utter integrity, supple phrasing, nuanced colorings and aching vulnerability. Her bright, strong voice filled Verdi’s lines and penetrated the orchestra without forcing. The only debatable element of her singing, as usual, was the quality of her sound, which has a tremulous vibrato and a slightly earthy, grainy texture.

The baritone Andrzej Dobber brought his muscular, rather bellowing voice to the role of Stankar, Lina’s father, an elderly colonel who, humiliated by his daughter’s transgression, tries to keep Stiffelio in the dark. The bass Phillip Ens was a stentorian Jorg, a severe, elderly minister who counsels Stiffelio.

Verdi’s opera is the big news, though. It is time for “Stiffelio” to take its place in the Verdi canon.

‘STIFFELIO’ (Tuesday) In 1993 the Metropolitan Opera presented a company premiere production of Verdi’s little-known opera “Stiffelio” as a vehicle for Plácido Domingo, who compellingly sang the title role of a 19th-century Evangelical Protestant minister facing a shattering spiritual crisis over the infidelity of his wife. Mr. Domingo is back for the revival of “Stiffelio,” the first Met performances since 1998. But this time he is in the pit, conducting. The title role is sung by José Cura, who reins in his burnished, sometimes wild tenor voice to give an intelligent and effective performance. As Lina, Stiffelio’s guilt-ridden wife, the soprano Julianna Di Giacomo takes over for Sondra Radvanovsky. New York Times

Stiffelio

Howard Kissel

January 12, 2010

New York Daily News

[excerpts]

What could be more thrilling than to "discover" a Verdi opera?

"Stiffelio," which returned to the repertory Monday night after 17 years, was not even performed at the Met until 1993. Is "Stiffelio" in the class of all the Verdi works mentioned earlier? No. Is it nevertheless an opera of great melodies and dramatic power worth getting to know better? Indeed it is.

"Stiffelio" concerns a Protestant minister whose attitudes toward sin are quite severe -- until he discovers his wife, whom he loves deeply, has been unfaithful to him. His desire to forgive her and to make her happy seem far more Christian than the severe things he declares from the pulpit. It is an intensely arresting plot, and Verdi's music brings all its emotional complexities alive.

The Met put together an exception cast to make a case for this unjustly neglected work. In the title role José Cura conveyed the minister's emotional anguish with deep poignancy. The power and directness of his singing and acting may have stemmed in part from his relationship with last night's conductor...

The role of Stiffelio's wife Lina was taken by the young American soprano Sondra Radvanovsky, who, like Cura, is as skillful an actress as she is a singer. Her huge, carefully controlled voice was glorious in her piercing solos. It shone splendidly in the ensemble numbers.

Verdi's Evangelical Preacher Stiffelio, Brooding & Raging, Returns to the Met

Bruce-Michael Gelbert

Q On Stage – New York’s Performance and Arts Review

On January 11, the Metropolitan Opera revived Giuseppe Verdi's "Stiffelio" (1850) and Plácido Domingo, protagonist of the 1993 Met premiere and 1998 revival, this time presided in the pit. For the work, Verdi set the then contemporary tale of a German protestant minister, Stiffelio (Stiffelius), also called Rodolfo Müller, whose wife, Lina, has an affair with Raffaele von Leuthold, a young nobleman, in her spouse's absence. Lina's father, Count Stankar, avenges the family 'honor' by killing Raffaele and Stiffelio, inspired by the Book of John, Chapter 8, about Jesus refusing to condemn "l'adultera" (the 'adulteress')-"Quegli di voi che non peccò,/la prima pietra scagli" (Whichever among you is without sin, cast the first stone)-'pardons' Lina. Verdi predictably ran afoul of the Italian censors with this controversial subject and, dismayed by the disfiguring changes they demanded, withdrew the opera after its first productions-in Trieste, and in Napoli, the Papal States, and Bologna (as "Guglielmo Wellingrode," about a minister of state, a version Verdi loathed), and finally in Barcelona-and extensively reworked it for an 1857 premiere in Rimini, as "Aroldo," now with a more remote, 12th century setting and a Saxon knight, returning from the Crusades, instead of a clergyman, as central figure. The lost score of "Stiffelio" resurfaced in the 1960s and the opera has since been presented in a number of cities, including Parma, Köln, New York (in Brooklyn and Manhattan), Boston, and London, in editions reflecting increasing scholarship.

After a somewhat tentative start, during which soprano Jennifer Check, in the supporting role of Dorotea, Lina's cousin, made one of the strongest impressions, the performance caught fire in the duet, which becomes a trio with Stankar (Polish baritone Andrzej Dobber), in which Stiffelio (José Cura), discovers that Lina (Sondra Radvanovsky), is missing her wedding ring and explodes with fury. Radvanovsky offered beautiful high, quiet singing in Lina's first act prayer, and her ensuing confrontation with Dobber's unforgiving Stankar boasted the requisite blood-and-thunder and sensitivity alike, in good measure. The first act's climactic largo septet and chorus-in which recurring lines "Fatal, fatal mistero/tal libro svelerà" (This book will reveal a fatal mystery) refer to a copy of Klopstock's poetic and religious "Messias" (Messiah), in which an intimate letter from Raffaele to Lina is hidden-and the ensemble's stretta, both forcefully kicked off by Cura, were as grand as they should be, thanks to the aforementioned singers.

Cura's brooding Stiffelio, bent on divorce, and Radvanovsky's contrite Lina, determined to confess to the man of the cloth what the husband would not hear, capped their portrayals with a penultimate scene "Opposto è il calle" (Opposite are the paths) of full intensity, and emotional subsequent scene in the church, suggesting the peace they have made with each other.

Rare 'Stiffelio' proves worth reviving at Met

Posted on 01/14/2010

DAVID A. ROSENBERG

Stamford Times

Hour Theater Critic

Although it has no familiar arias and its plot strains credulity, Verdi's "Stiffelio" at the Met Opera is a mesmerizing affair. Somehow, the idea of an evangelical minister who is perfectly comfortable with abstract morality but thrown when faced with personal demons, is more scarily relevant than ever. "Forgiveness is easy for a heart that has not been wounded," he says.

José Cura digs into Stiffelio's sorrows with restraint, while Andrezej Dobber is a stentorian Count who manages to skirt the role's more over-the-top actions, such as threatening to shoot himself. The atmospheric production (sets and costumes by Michael Scott, lighting by Gil Wechsler) contributes to the evening's success. The superb Met chorus under Douglas Palumbo doesn't have much to do but, as always, is unbeatable. "Stiffelio" is no "Rigoletto," "Traviata" or "Aida," but its smaller canvas is both satisfying and compelling.

AVA graduate makes an impressive Met debut

David Patrick Stearns

13 January 2010

Philadelphia Inquirer

NEW YORK - Verdi's Stiffelio is an infrequent visitor to the Metropolitan Opera - or any company - and couldn't be a more unlikely vehicle for an important vocal debut. Yet Philadelphia-based tenor Michael Fabiano, one of the Academy of Vocal Arts' most promising graduates, made it work for his Met debut on Monday amid the building critical mass of his career.

The linchpin, though, was Monday's Stiffelio opening, in which Fabiano could have been hemmed in by the towering presence of tenor José Cura singing in the title role and none other than Placido Domingo conducting in the orchestra pit. But instead of fading into the considerable scenery of the Met's handsome Giancarlo del Monaco production, he was more than noticed, receiving a healthy ovation in his final curtain call.

Stiffelio itself comes off remarkably well. I don't remember being nearly as taken with it when the production was new in 1993 (when Domingo was singing rather than conducting), but now it seems like time extremely well spent. The title role's piety doesn't exactly harness Cura's sex appeal, and vocally, he has reestablished himself as a major Verdi tenor.

Stiffelio

Elizabeth Barnette

Classicalsource

While Verdi's “Rigoletto”, “Il trovatore” and “La traviata” are amongst the most popular works in the repertoire, “Stiffelio”, immediately preceding this trio in 1850, is almost unknown for reasons which have nothing to do with its musical qualities, but with political censorship. Its plot, the story of a Protestant minister who eventually forgives his unfaithful wife was so unacceptable to the censors in Trieste that they demanded extensive changes. In Verdi's eyes these ruined the substance of the libretto, hence he withdrew Stiffelio, re-worked part of it into his 1867 opera “Aroldo”, and abandoned the rest. The score was believed to be lost until the 1960s, when manuscript copies of “Stiffelio” and “Guglielmo Wellington” (a non-authentic adaptation) were discovered in Naples and Vienna; a few performances were attempted, but all with censored texts.It was not until 1993 that a new critical edition was prepared by Kathleen Hansell from a variety of sources – the autograph score of “Aroldo”, the censored manuscripts, and remaining original materials at the composer's home, Sant' Agata, which were made available by the Verdi family for the first time. After The Royal Opera (Covent Garden) premiered this ‘new’ score in January 1993, the Metropolitan presented it that same year, and again in 1999, with Plácido Domingo in the title role.

Domingo returned for this revival as well, but this time to conduct, which he has been doing for many years now, but his technical shortcomings are still in evidence. The co-ordination between pit and stage left much to be desired, he frequently brought the orchestra in late, and at the end of Stankar's aria in the third act things came apart completely for a couple of bars.

The Argentinean tenor José Cura found himself in the peculiar position of having to sing a rarely performed role conducted by the man most closely identified with it. His voice is on the dark side, almost covered at times, but his dramatic portrayal of the anguished, betrayed minister supplied the intensity sometimes lacking in his vocal delivery.Sondra Radvanovsky as his wife Lina gave a fine dramatic performance as well, but the palette of her vocal expressiveness is severely limited. She produces plenty of sound, but of a rather strident and piercing kind, and frequently below pitch. One misses roundness and modulation in her voice, and nuanced, controlled softer dynamics.

Giancarlo del Monaco's production, featuring a dark, wood-paneled library for the first and beginning of the last acts, a churchyard for the second, and the interior of a church for the last scene, perfectly conjured up the oppressive atmosphere of the drama. Although there are no arias to whistle on one's way home, “Stiffelio” is by no means lesser Verdi. It somewhat foreshadows “Otello” in dramatic structure, “La traviata” in the scene between Lina and her father, and the chorus in the last scene is truly extraordinary. Although the subject matter was too radical for the 1850s, nowadays this impressive work surely deserves a place in the repertoire.

|

|

|

|

Art by Denise

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Lina Speaks Radvanovsky on Cura

I’ve said it before in these pages: The conductor can make or break an opera. In the Metropolitan’s current revival of Verdi’s “Stiffelio,” an almost unknown work, that conductor is Placido Domingo, once one of the “3 Tenors,” for whom the Met revived the work (as a singer) in 1993. Despite his obvious passion for the music, and his considerate accompaniment of singers (as only a fellow vocalist might empathize), he is not a born conductor. I won’t say that he “broke” the opera, but it turned into a rather inert object most of the time, lacking sweep, structural cohesion, and rhythmic spring, further weakened by regrettable pit/stage ensemble discrepancies. [...] Priestly celibacy became policy in the Middle Ages, around the twelfth century. However, in the “Eastern Rite” (Catholicism as practiced in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and Ukraine) priests often are married. And even in today’s Roman Catholic church (since 1980), if a priest comes into the church from another faith that permits marriage, he may remain that way as a Catholic (evaluated on a case by case basis with special petition to the Pope). But in provincial nineteenth century Italy, out of the question! Verdi and his librettist set the story in a fictional evangelical sect in the western (Tyrol) part of Austria, having learned that a similar group historically had been persecuted there. In Italian, a “stiffelio” (or “stiffelius”) is a frock coat, perhaps referring to the priestly garb that imprisons the title character in a self-righteous cocoon of desired vengeance, until his own sermon reminds him of Jesus’ injunction to forgive sin and sinners. The singing had its good moments. Lina, the adulterous (most likely sexually neglected) priest’s wife, was sung by Julianna di Giacomo, and she produced some very impressive soft full bodied sounds. As Stiffelio, the “Argentinian tenor Messiah” José Cura sounded forced at times, though warmly lyrical at other times. The other roles were similarly fulfilled, but alas, not particularly memorable. “The artist must peer into the future, perceive new worlds amongst the chaos, and if at the end of his long road he eventually discerns a tiny light, the surrounding dark must not alarm him. He must pursue that path, and if occasionally he stumbles and falls, he must rise up and continue.” Verdi Frank Daykin, Innovative Music Programs

Verdi composed Stiffelio after Luisa Miller and before his trilogy, which ended his so-called ‘years in the galleys.’ The libretto was written by one of his usual collaborators, Francesco Maria Piave, based on the book ‘Le Pasteur ou LÉvangile et le foyer,’ written by Souvatre Emile and Eugéne Bourgeois. The story follows a Protestant minister (Stiffelio), back home after a trip, when he discovers that his wife (Lina) has been unfaithful with a nobleman (Raffaele). Lina’s father (Stankar) tries to keep this forbidden relationship secret. When the pastor learns of it, he goes into a profound spiritual crisis and a severe internal conflict that will be resolved during the Sunday sermon when, before the faithful, he quotes from scripture, “Let he who is without sin cast the first stone.” Back from Oblivion The opera was premiered in Trieste in 1850 and quickly disappeared from the stage. Stiffelio remained in oblivion until 1960 but (in my opinion) it was the performances that took place at the Met in November 1993 which led it to be produced at other theaters around the world. […] José Cura (Stiffelio) offered a bravura tenor version suitable for the character in moments of anger, which sometimes resulted in a certain lack of refinement and prevents him from achieving enough lyricism in those moments when the shepherd must keep his moderation. His total dedication and fierceness [of delivery] provided for an undisputed ovation at the end Sondra Radvanovsky (Lina) performed efficiently and with absolute brilliance and a powerful voice as the repentant pastor’s wife, despite a vibrato heard at some points. Andrzej Dobber (Stankar) sang reliably but without the brightness typical of the role. The Met’s very good orchestra was conducted by Plácido Domingo…with some loss of intensity in the interpretation of the score. I was fortunate to have attended one of the performances in November 1993 with Levine in the pit and the result was far superior to the performance today. But I must note that, having been in this theater with Barenboim, Kleiber, Mazel, Levine and many others I have never heard an ovation like that which was levied on Sunday.

|

|

|

José Cura Singing for Survival, Love

Lee Hyo-won

The Korean Times

25 April 2010

Tales of artists starving for their beloved art are aplenty. Singing, for José Cura was a matter of survival first, however, and the affection came later. But initiatives seem to be of little consequence for the superstar tenor's palpable passion for music has put him on the world map.

``In Argentina in the 1980s, to start singing was a question of survival. Almost all orchestras and choirs were put on hold, and to conduct was an almost impossible task,'' Cura told The Korea Times in a recent email interview ahead of his concert here next month.

Born in Rosario, Argentina in 1962, Cura was originally trained as an orchestral conductor, and only started singing in his late 20s. ``When I discovered I could also sing, I started doing it just as a way of paying my family's maintenance. Eventually, singing become my career and I love it.''

The 47-year-old is reputed for his intensely original interpretation of operatic roles, which earned him the nickname as ``the fourth tenor'' after the Big Three (the late Luciano Pavarotti, Placido Domingo and Jose Carreras).

But he comes first as a pioneer in his own right, as the first artist to sing and conduct simultaneously, both live and on recordings. In 2003, he rewrote operatic history when he conducted ``Cavalleria Rusticana'' and then stepped onto the stage after intermission to sing.

When asked about how he balances the two activities, as well as composing and teaching, Cura simply said, ``No secrets: great preparation and hard work.'' His know-how for maintaining a great voice was also succinct and to the point ― ``To have a normal life, in all senses: eat healthy, exercise, sleep properly,'' said the former body builder and kung fu black belt.

In his upcoming recital on May 4 at Goyang Aram Nuri Arts Complex, Gyeonggi Province, the prolific artist will offer fans an array of arias, including from operas by Verdi and Puccini such as ``Otello'' and ``Tosca.''

Soprano Kim In-hye will accompany him in duets, while Marlo de Rose will conduct the Korea Symphony Orchestra. But de Rose will step down from the podium when Cura conducts the overture from Verdi's ``Vespri Siciliani'' and ``La Tragenda'' from ``Le Villi,'' an early piece by Puccini.

When asked if a particular opera role has a special place in his heart, he said no. ``All the characters I currently interpret have a special place in my heart. I would not perform them if not, as the public notices when you are not at ease in a role.'' Fans can thus indulge in the show and see him transform from the grieving Otello to the love-struck Pinkerton.

The singer expressed enthusiasm about sharing his music with the Korean audience. ``Contrary to what we think in the West, Asian people are extremely passionate and demonstrative. But also, the demonstration of love is always done with a great deal of respect.''

Meanwhile, in addition to performing, Cura is dedicated to fostering young talent through teaching in London and leading the British Youth Opera Organization as its vice-president.

He said he reminds students, as Oscar Wilde said, ``Be yourself; everybody else is already taken.''

Moreover, he explained that classical music is for everyone. ``This music does not belong to an elitist group, that is not the `soundtrack' of an esoteric black mass performed only for a little intelligentsia, but great art,'' he said, just as timeless works of art are created by the people for the people.

|

Budapest Opera Ball

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JOSÉ CURA Be yourself Repetice (Repeat)

|

|

|

|

CAV and Pag in 2010

DVD

|

Opera Now's Featured DVD of the Month October 11 |

|

|

Referenced Review |

|

Mascagni: Cavalleria rusticana; Leoncavallo: Pagliacci

Zurich Opera House

Arthaus DVD

BBC Music Magazine Review

Reviewed by George Hall

In this 2009 Zurich production each half of the familiar verismo double bill is presented in the same spare, semi-abstract sets, which work better for Cavalleria than for Pagliacci. The former offers the usual would-be realistic vignettes of village life as the background to the main events, where the acting is presentable. Paoletta Marrocu provides visual intensity as Santuzza, though not enough voice. Equally limited vocally is Cheyne Davidson’s Alfio, though his Mafioso-boss-like swagger fits the bill. Liliana Nikiteanu’s pretty, carefree Lola hits the mark.

But the star here is undoubtedly José Cura who offers himself up for a taxing central assignment in both operas. He plays a stern and nicely concentrated Turridu in Mascagni’s Sicilian tragedy, vocally imaginative if a touch idiosyncratic in his employment of a mezza voce that verges on crooning. Even so, his is an appreciable achievement.

If his Canio in Pagliacci is not on this level, it’s because Grischa Asagaroff’s staging debases Leoncavallo’s masterpiece and its central character along with it. A good performance of a great protagonist achieves a measure of tragedy as we watch a human being fall apart and descend to murder. Cura’s Canio has clearly fallen apart long before this opera begins and has nowhere to go, while much of the surrounding staging is just vulgar tat. Carlo Guelfi is an ineffective Tonio and Fiorenza Cedolins a dowdy Nedda, though Gabriel Bermúdez makes a personable Silvio.

Cav and Pag DVD

Zurich Opera Blu-ray, Video Quality

Jeffrey Kauffman, June 26, 2010

These two iconic one-act operas arrive on Blu-ray from ArtHaus Musik with AVC encoded images in 1080i "live" transfers with aspect ratios of 1.78:1. These two operas offer a wonderful example of the versatility of Blu-ray in providing really disparate high definition images. Cavalleria plays out almost entirely in shades of blue, and that tint is gorgeously rendered on this Blu-ray. Even with the dark color scheme, detail is sharp and precise, with wonderfully inky black levels and excellent contrast. Pagliacci, on the other hand, is like a Fellini movie, one audacious color after the next, and all of it perfectly saturated and robustly presented. Note in the prologue how you can virtually count every feather on Tonio's shoulder. Throughout the second presentation, detail is if anything sharper than on Cav, simply because it's so much more brightly lit and the colors are so much more boisterous. Depth of field is really quite remarkable on this Blu-ray as well; make sure to pay attention to the subtly changing cloudscapes that float behind the unit set, especially with the very subtle lighting changes that take place.

Both of these pieces are unusually expressive, all the more interesting in that their composers never quite caught the magic a second time despite trying ardently to do just that. We're offered two mostly excellent lossless mixes here, a DTS-HD Master Audio 7.1 mix and an LPCM 2.0 stereo fold down. There's virtually nothing to complain about here that's due to the fidelity of the recording. We're offered a crisp and clear accounting of both scores, lushly warm and bracingly emotional. My only qualm has to do with the balance, and I'm virtually positive it's a micing issue. The multi-tiered unit set is really pretty far upstage, and when Cura opens Cav, for example, he's on the second level, probably quite far back from the fly microphones. Therefore he sounds like he's singing from a valley two or three town over. When the actors move downstage, both during Cav, and later in Pag, this problem disappears completely. Both of these scores feature achingly beautiful string sections, and conductor Stefano Ranzani does an admirable job in milking the rubato aspect out of both of these pieces, which the DTS 7.1 mix supports in absolute clarity.

While both of these relatively brief pieces (they each clock in at about an hour and fifteen minutes) deal with jealously, love and murder, their tones really couldn't be more different. Cavalleria Rusticana is an unironic portrait of a tragic ménage-a-trois of sorts. Turiddu (José Cura) had once loved Lola (Liliana Nikteanu) before his military service got in the way. Lola ended up marrying Alfio (Cheyne Davidson), and Turiddu ended up with Santuzza (Paoletta Marrocu). Cavalleria Rusticana plays out in real time in and around Easter as these two mismatched couples find their lives intertwined, leading to a predictably tragic conclusion. This is "kitchen sink" opera, rather prescient in fact of dramatic sensibilities that wouldn't take hold of traditional, non-sung theater, for another half century or so. Cavalleria is also a fascinating study in Verdian accompaniment. Note, for example, how little actual singing there is in the opening scene. Instead we get a lot of very expressive orchestral playing as Santuzza begins to realize that Turiddu has been unfaithful. This is a brisk and violent journey through some frankly twisted emotions, and it's rather remarkable that a little known composer, one who would try but fail to recapture his early success with Cavalleria, was able to so aptly capture the furious energy of these characters.

Pagliacci, on the other hand, is all about artifice. This one-act famously opens with an intentionally ironic prologue which both serves as a credo for verismo while simultaneously warning the audience not to take anything too seriously, since everyone know they're onstage and are playacting. It's one of the most fascinatingly self-reflective and oppositional moments in all of opera, and it is testament to Leoncavallo (who wrote his own libretto) that the genius of these two completely disparate ideas are presented so naturally and artfully. Pagliacci of course utilizes characters from Commedia dell'Arte in a very non-comedic way, as Canio (Cura), an itinerant actor, becomes enflamed with jealous rage at the thought of losing his wife, Nedda (Florenza Cedolins). Canio is almost the Stanley Kowalski of verismo, a big, brooding character who is violent one moment and then surprisingly vulnerable and heartwrenching the next. Cura plays him for all he's worth, and delivers a staggeringly effective "Vesti la giubba" to close out Act I.

While both of these presentations use the same unit set, at least for backdrop, they couldn't be more different in their production design. Cavalleria, as befits its quasi-religious, dour mood, is muted, abrupt, clad in dark colors that are nearly monochrome. Pagliacci bursts off the screen from the prologue's first moment, a riot of color and energy, big, boisterous and only tangentially incredibly tragic. It's actually rather remarkable to see this famous pair presented in such disparate manners. Often directors try to "meld" the styles of the two operas to achieve some sort of quasi-cohesive unity (placing Pag's prologue before Cav is just one example), but here director Grischa Asagaroff seems to exult in the obvious differences between the two and doesn't shy away from them. Indeed the very different approaches, not just in production design, but in the performances, help to give the evening a remarkable variety of emotional impact. Too often these two done together are two and half hours of relentlessly "down" energy, but after Cav's admittedly dark opening gambit, even the knowledge of the coming fury of Pag's ending doesn't take away from the appropriately circus-like energy which infuses the second half of the pairing.

Cura is formidable in both of these roles, though I personally give the edge to his Canio. Marrocu is beautifully subdued as Santuzza, and Nikiteanu and Davidson do admirable work in roles which can be quite thankless. On the Pag side of things, Cedolins sings wonderfully as Nedda and portrays the fractured soul of this trapped character quite brilliantly. Gabriel Bermudez has energy and charisma galore as Silvio, and Carlo Guelfi is suitably despicable as Tonio.

Leoncavallo may not have gotten his way in terms of crafting an evening featuring solely his creations, but the now standard pairing of Cavalleria Rusticana with Pagliacci proves that over a century later it can still be a one-two punch of rare theatrical power and presence. This Zurich Opera production does both one-acts proud.Cav/Pag has become an iconic pairing from virtually the first moment the two one-acts were joined at the figurative hip. With a star turn by Cura in the lead roles, and an excitingly varied physical production, this Zurich Opera presentation plays these tragic pieces for all they're worth. These "real life" small scale pieces contain some of the biggest emotions of early 20th century repertoire, and you'll be hard pressed not to have a visceral reaction to them here.

Pietro Mascagni's "Cavalleria rusticana" and Ruggero Leoncavallo's "Pagliacci" speak to one's heart and soul. They are regarded as the most absorbing tragedies of Italian music theater. Adultery, jealousy and betrayal are leading to passionate conflicts that jointly connect both operas. The impressively embellished stage waives exaggerated decoration to underline the unflattering realistic brutality. Both operas are supported by a musical variety of great arias, short duets and amazing choir passages that add to the unveiled expression of feelings. As a special guest the Argentinian Tenor José Cura stands out with his fascinating singing and acting performance. HBDirect

MASCAGNI: Cavalleria rusticana

LEONCAVALLO: Pagliacci

Mark Mandel

Opera News

August 2010

[Excerpts]

Cavalleria: Marrocu, Nikiteanu; Cura, Davidson. Pagliacci: Cedolins; Cura, Guelfi, Bermúdez; Orchestra and Chorus of the Zurich Opera House, Ranzani. Production: Asagaroff. Arthaus Musik 101 489 (DVD) or 101 490 (Blu-ray)

Verismo’s Castor and Pollux were once inseparable. Cavalleria Rusticana now appears less frequently than Pagliacci, which often partners a less similar work or even plays alone. Perhaps Pagliacci, the more ironic of the two operas, better fits our emotionally detached times. Its well-known aria “Vesti la guibba” might make it an easier sell, and it’s certainly true that Pag’s Nedda is less difficult to cast than Cav’s Santuzza. But in the production captured on this release, with the twins reunited at Zurich Opera in 2009, Cavalleria Rusticana comes off better.

Stage director Grischa Asagaroff updates both operas to the mid-twentieth century but plays Cavalleria straight. He’s blessed with skilled thespians in Paoletta Marrocu (Santuzza), José Cura (Turiddu) and Zurich stalwarts Cheyne Davidson (Alfio) and Liliana Nikiteanu (Lola). The interaction among the four of them is compelling, often searing.

Marrocu is a soprano Santuzza of quick vibrato, acidulous tone, fair power and fiery intensity. She delivers a chesty “A te la mala Pasqua” and a scorching “Spergiuro!” Cura’s baritonal tenor has both heft and beauty; his singing sometimes is marred by a coarse effect, such as a gulped breath and yelped A-flats in the siciliana.

Cura doubles as Canio in Pagliacci, playing him as highly intoxicated from beginning to end. Canio stagger about the stage, imbibes openly, picks his nose and blows it on a stranger’s cap. Cura’s singing is deliberately loose of rhythm and pitch, bizarrely phrased and shaded, because Canio is dead drunk. It’s a virtuoso performance in thrall to a conceptual blunder.

The violent climax packs a punch, with Cura in ringing voice. Canio, not Tonio, whimpers “La commedia e finite!”

On-Stage: Vienna

CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA by Pietro Mascagni

PAGLIACCI by Ruggero Leoncavallo

Renate Wagner

Der Neue Merker

February 20, 2010

(VIENNA/ State Opera)

It was José Cura's Vienna debut in the role of Turridu, and his first time to sing both Turridu and Canio at the Vienna State Opera in the same evening. (This is one of his famous 'feats'; one he has already done successfully at the Met, in Zurich and in Cologne.) The evening turned into a very personal, entirely individual triumph for him, deservedly so. Had one not been aware of it already, here it was confirmed --José Cura is the King of Verismo.

Whoever expects him to be in "line" with beautiful singing and belcantesque languishing will always be disappointed. When it's a matter of dedicating personality and voice totally and completely to a highly dramatic role (which also makes him into one of the best Don José of our stages), he will be topped by hardly anyone at present. In these two roles, his singing was certainly not flawlessly clean, but always gripping, captivating with its unsparingly trumping, unwavering high notes and remarkable power. (Were he not mature and likely to consider carefully what he does, one would worry about how he handles his material.) To be added in this case: his accomplishments as an actor --and those from a singer, who, as one knows and has witnessed with distress, can occasionally also stand around as if quite bored. That does not happen here.

Turiddu is head over heels in love with Lola, so much so that he takes leave of his senses, that he risks his life--and can but reject the troublesome Santuzza, turning her away angrily but without being brutal. For when he is about to die, she is in a touching way the only one on his mind. Never before has it become so clear that the provocation, which Turiddu is directing here against the society in which he lives, is virtually a death wish. And that's the way he dies, too, quite in the background, throwing away his knife after a few feints with the weapon and walking into Alfio's knife. One was privileged with the view from the gallery in this case; from below one could probably not see it quite so well.

Cura's Canio, too, is driven by aggressive restlessness and anxiety; he lives with his suspicions about his wife, determined to find them verified. He is not an elevated-heroic-tragic but rather a seriously affected, wild-suffering man, who avoids big scenes-- also one, who does not break down in despair at the end, but rather looks at the dead almost disaffectedly astounded, asking himself what it is he has done.

The audience was wildly enthusiastic, and as far as Cura is concerned, rightly so.

[…]

This one-act opera (i.e. "Pagliacci") is usually considered to be the stronger one because the music is more agreeable and popular, the action more colorful than in "Cavalleria"; but on this evening, "Pagliacci" sagged hopelessly whenever Cura was not on stage.

[…]

The orchestra under Asher Fisch did not excel in either of the one-act operas; there were also miscommunications between singers, chorus and pit. In short-had it not been for Cura's triumph as Primo Uomo of Verismo, one would have dealt merely with average repertoire once again, the kind which appears to be prevalent these days.

José Cura in (vocal) Materials Battle

Die Presse

February 22, 2010

For the first time, tenor José Cura gave a guest performance in Vienna in both "Cavalleria" and "Pagliacci" on the same evening. Musically Cura is fighting a battle-- a (vocal) materials battle.

One thing Jose Cura cannot be accused of in any way on this evening of the Siamese verismo twins "Cavalleria rusticana" and "Pagliacci": that he didn't throw himself into the battle unconditionally. Aren't there after all performances every now and then, where he seems to treat what's happening on stage around him rather with contempt? No sign of it this time: he gave shape to the faithless Turridu, embodied by him at the State Opera for the first time, with just as much impetus as to the duped Canio, drawn to be quite clumsy, for whom what's play and what's real merge in front of his alcohol-hazed eyes not just (as events draw) toward the fatal ending.

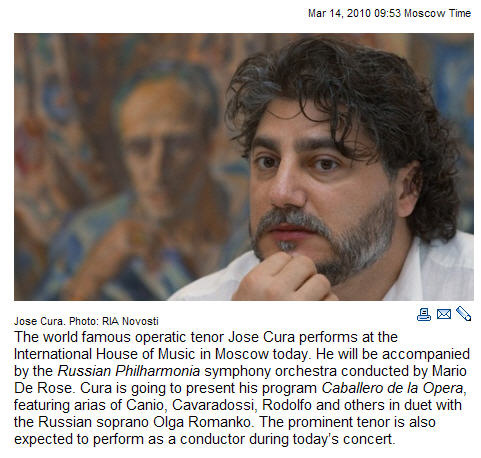

Cura in Moscow

José Cura: La Ópera Es Como Una Mujer Atractiva, Pero Difícil

Ritmo de los Tiempos

[excerpt]

Prior to his performance on the stage of the International House of Music in Moscow, RT asked the outstanding Argentine tenor José Cura about similar situations he experienced in the course of his concerts.

"This happened to me long ago, in 1995, while singing Umberto Giordano's opera "Fedora" in Trieste, Italy. At a certain point in the third act, my character has got to read a letter which informs him that his mother has died. It's a really tough letter; very sad. But at the last performance (of the run), in place of the letter, I was given the photo of a woman in the nude. Let me tell you, that was something else, was really dreadful because to open this letter and be obligated to cry was a tremendously stressful, tension-filled situation. My thought upon opening the mailing and discovering the naked woman: "I cannot, must not laugh!" This is one of those moments where you cannot laugh; it would be lethal; everything is going to fall apart, 'decompose' as we say in my country. Well, I close the letter quite discreetly; out of the corner of my eye I see everyone in the wings bent over laughing, eagerly waiting to see what I was going to do. I closed the letter without attracting attention to it and put it into my pocket. O miracle of miracles! I did read the letter from memory. But it was an absolutely terrible moment when things could have turned sort of tough because it's one thing to play a practical joke, but it's quite another matter if it has the potential to ruin the moment. This is the scenario: Once you start to laugh, you're not going to stop. In a way, you can keep yourself in check when crying; you can even use it as a tool, but laughing, that's something else. In this scenario, the impulse is unstoppable."

| Thanks to Alexey for all the great photos!

|

A handkerchief's Bohème

Place de l'Opera

Alessandro Anghinoni

29 March 2010

I could not choke back my tears: the Bohème with José Cura and Barbara Frittoli was too much to be heard with dry eyes. The conducting of Massimo Zanetti is a lesson about interpreting Puccini and bringing a score to life.

My last tears for a Bohème performance were 2008, as I saw the first distribution in German cinemas of the film with Villazón and Netrebko: but those were tears of laughing! The unbearable exaggeration of grimaces in the close-ups and the unwanted kitsch of some special effects forced me to hold my belly during the projection. This time I talk of other tears.

I could not even imagine a more touching and complete rendition of Rodolfo then the one José Cura has given on this Sunday afternoon. The quality of his voice, now much more mature and baritone-like as it was some 10 years ago, is hardly overestimated. The top may be not as amazing as it used to be but the capacity of penetrate in the heart of the role and convey feelings is fantastic, and something you can’t measure. I was struck by his simple saying his last words after Mimi’s death: this is real verismo!

Such intensity of interpretation was equalled by the Mimi of Barbara Frittoli, the great Italian soprano, who much like Mirella Freni, is able to combine technical perfection, lyrical timbre of the voice and dramatic intuition, putting everything in service of the music. No excesses, no use of easy effects like sobbing or pushing the notes: just the serene sovereignty of a singer with a profound sense of the humanity of Puccini’s music – and all the vocal means to express it.

The two protagonists had something we should never give for granted: a perfect diction of the text! The librettist Giacosa was desperate, during the composition, because Puccini pretended continuous changes and chiselling of the wording. Diction is crucial in Bohème: the young soprano and member of the ensemble Christiane Kohl knows it and sung a vocally stupendous Musetta, with a clarity in the articulation of the text that must be praised.

|

||

|

Concert in Athens

Excerpt from Kathimerini Article (Athens)

20 April 2010

Excerpts

Under the name of José Cura and for the good cause of Thorax, a remarkable opera night with Katerina Roussou at the Megaron

Celebrity Invitational, led by the President of the Republic and Mrs. May Papoulia, at the Opera Gala on Saturday 17/4/2010 with the Argentinean tenor José Cura in selected repertory of most favourite arias and, by his side the young opera singer, the internationally rising mezzo soprano Katerina Roussou, who sang along “with the giant”, but also offered two solos, two difficult Mozart arias, with her caress-like voice and interpretive sensitivity..It is hoped that this fund raising concert would be supported not just by the wealthy but also by the friends of opera, who were rewarded with an excellent performance by José Cura, who not only sang with his rich metallic voice that packs arenas and stadia, but also captured his audience with his human, cozy attitude on stage. He started his program with the famous Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci aria, making his entrance by the left corridor of the hall, singing. As soon as he got on stage, the whole place livened up, following the pace of the artistic creation of a great voice. [….] With a white shirt, with few well-considered gestures, but in constant motion, Cura was singing, conducting at the same time and indicating the soloists of the orchestra, for each musical piece, asking them at the end to stand up to share the applause with him. A great voice and a big heart, José addressed the audience, speaking of the big cause and its importance. “I have come with great joy to contribute in the success of the cause of Professor Roussos, but also to sing along with a young singer, who, though still a student in Ljubljana, is already singing on international stages with remarkable success. You will listen to us singing together…”

[Cura] thanked the audience that filled the Megaron Hall for this important medical cause and turning to Balcony 8 to address Professor Roussos, who was sitting next to the Presidential couple and the Athens Mayor Mr. Nikitas Kaklamanis, asked: “Professor, how much more do we need?” “Millions,” answered Mr. Roussos. “We will sing again”, Cura said, “till we make it!” We need to note here that Jose Cura received only a token fee and he offered the rights of his production company from his CDs and the money that comes from their sales to be used for the causes of Thorax! This is why the world famous tenor Jose Cura came to Athens as a host, a presenter and a friend, paving also the way for Katerina Roussou…]

José Cura in Athens: Le lacrime che noi versiam son false?

25 April 2010

José Cura's Recital was the blockbuster-surprise of 2010. Tickets had sold-out a week in advance and the demand was still very high till the very last minute.

This wasn't Cura's first time in Athens: His Radamés in May 2001 had fascinated the Greek audience and his 2002 recital was a blust too. On top of that, Cura had been invited to sing in July 2004 on the frontier island of Inousses as part of the festivities for the Athens 2004 Olympic Games.

The Argentinian tenor was back to Athens for a recital that took place at the Athens Megaron on April 17, a recital that shed more light on Cura-the artist than Cura-the singer.

One doesn't have to be following Cura's career to understand what is obvious: Cura constantly resorts to mannerisms that render his singing uneven. His accuti can make you nervous only by watching the tenor execute them - the way he rides the passaggio and passes the voice to the head, pushing, pushing and pushing, creating so much pressure in his skull that a high note above A, maintained for a bit more than a few nanoseconds could lead to an explosion.

Certainly he knows his flaws and can by-pass them artfully or use them in order to serve the drama. But after a 90-minutes recital, and after having sung this way, Cura comes on stage and sings a Nessun Dorma that leaves you breathless - round, sustained high notes included - and thinking "But if he CAN do it like this, why doesn't he?".

Just like during the 2003 recital at the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, Cura played hide-and-seek with the audience, making his entrance from between the audience while singing Tonio's "Si puó? from Pagliacci - á la Del Monaco. His "Vesti la giubba" that followed gave me the goosebumps, same for Otello's "Dio, mi potevi scagliar" and "Niun mi tema".

During Part II, Puccini was the composer of honour and his music seemed to be fitting Cura like a glove: Mario, Dick Johnson, Pinkerton, sung with passion (especially Dick) and in the most dramatic fashion though without ever overcoming his upper register problems.

Cura's companion in this journey was the young, Greek mezzo-soprano Katerina Roussou. Roussou, still a student of vocal arts in Ljubljana, displays an interesting instrument, a natural voice that better served Carmen's Seguidille than the unfortunate Angelina that I found to be too risky a choice for the warm-up. Cherubino's "Non so piú..." during the encores, verified that the vocal material exists but it's still immature and there's a long way to go.

What stroke me the most was Cura-the entertainer: he monkeyed around the orchestra, sang from all possible spots in the Hall, flirted with the - usually capricious and grumpy- (female) concertmaster, he joked with the audience, the organisers, even the President of the Hellenic Republic that was present (may we remind that the Greek President is an honorary citizen of Milan and a frequent visitor of the palco reale of La Scala), and displayed excellent communication skills.

Kudos to the National Symphony Orchestra of ERT that played unexpectedly well -for a change- especially Puccini's La Tregenda from Le Villi, and seemed to enjoy the collaboration with maestro Mario de Rose.

Backstage, a long queue waited for an autograph and a photo with José Cura who didn't let down his fans.

|

José Cura in Concert in Seoul

|

||||

|

|

Otello in Berlin!

José Cura - Multitalented and Outstanding Otello Interpreter

Berliner Morgenpost

Felix Schnieder-Henninger

Thursday, April 29, 2010

A singer, composer, conductor and photographer, José Cura is considered nowadays to be one of the most versatile artists of his generation. Born in Rosario (Argentina) in 1962, José Cura came to Europe in 1991, where he made his debut in Verona in 1992.

Performances in Turin, London and Paris followed. 1997, he made his debut at LaScala in Milan, 1999 at the Met. He is famous for his poignant, powerful and unmistakably individual interpretations of roles, among them Verdi's Otello and Don Carlos. Felix Schnieder-Henninger interviewed him.

Your first Otello?

José Cura: My Otello debut took place in 1997 at the Teatro Regio in Turin in a concert performance. The Berlin Philharmonic was playing under the direction of Claudio Abbado. Crazy, or what! I was 34 years old at that time and my interpretation was accordingly lyrical and stormy.

Has your view of the role changed since then?

Cura: After fifteen different productions and more than one hundred performances, one's interpretation changes radically. I have matured as an artist and as a human being - and the role along with me.

What does Verdi mean to you?

Cura: Verdi revolutionized opera. Before him, the opera was a place of pleasant sounds. The music attained little emotional depth. Then Verdi came and exclaimed, "Enough of that! Stop with this 'bel canto', this singing for beauty. Opera is theater, is 'melodramma'!"

How do you explain the South American tenor-miracle?

Cura: A few years back, all great tenors hailed from Europe, and no one thought anything about it. No one asked: "Why are all the tenors European?" - Why is it that now everyone is astonished that there are many good tenors in South America, too?

Your first opera?

Cura: I did not experience my first opera until I was 24. That's when I sang a very small role in Massenet's "Manon". To be honest, I hated opera as a teenager. I had this notion that opera might bore me to death - it's the way most young people think of it. For this reason, I am very much committed these days to proving and demonstrating the opposite to a younger generation.

What is the best way to get through the long hours on the plane en route to the next stage?

Cura: I love my time on the plane. Those are precious moments where one doesn't get disturbed and can read, write or design something with concentration. I have mapped out many drafts for projects on the plane and that's also where the crucial sentences for my novel were generated.

After opera singer, what would be your dream job?

Cura: Opera singer is actually not the job of my dreams at all. However, it is a privilege to be a good singer.

José Cura Sings at the Deutschen Oper

B.Z.

Martina Hafner

28. Mai 2010

He was considered the most erotic tenor in opera, first acclaimed and then torn to pieces. But Argentinian tenor José Cura (47) has survived. Tomorrow he sings in Verdi’s Otello (in Italian with no ‘h’) – the man who kills his wife Desdemona (Ajna Herteros) from jealousy.

Herr Cura, are you glad to sing a killer?

Otello is a victim who kills himself in the end. But clearly, killing is his job. He is a mercenary.

Do you like this Otello character?

Not at all, but I like to sing the role. He has a horrible soul, negative and self-destructive. He sees betrayal everywhere because he is a traitor himself. He looks everywhere to find a murderer, because he is one himself. A very modern theme, incidentally.

In what way?

Otello was a Muslim who converted to Christianity so he is accepted by society. And then he is hired to exterminate Muslims. It is nearly prophetic, the way in which Verdi set the conflicts, when you think of the wars today.

How will you look in the production?

I will be painted black. I understand, of course, why you ask that, since in Germany almost anything is possible of stage!

Andreas Kriegenburg productions are very modern. Do you feel comfortable with it?

I do not agree completely with him but as a professional, I will follow his approach. And it’s consistent. That is now required.

You were once called the tenor of the 21st, then you were savaged. Where do you stand today?

At the time I was at a record company, where every day there is a century-tenor. Many disappear again. But I am still here.

You were called the testosterone bomb of opera.

On stage. Privately, I have been with the same woman for more than 30 years.

What do you think of Argentina’s chances in the World Cup? Will your country win?

The Spaniards play the best football but they can be beaten by a more aggressive team. It’s like show business.

Oh? In what way?

When I started, it was important to know as much as possible. Today it is enough to win a competition on TV—and you are the best singer on the planet!

Do you do anything to stay physically fit?

There was, before I gained about 20 kilos. But I have so much to do, I direct, I conduct, I write books. My wife says that these are all excuses to not exercise. She’s right. I plead guilty!

Following a successful campaign against the Turks, Otello, a

general in the Venetian service, returns to Cyprus. A storm before

his native coast plunges the homecomers into a chaos of natural

forces, from which they only just manage to escape. On land, they

are awaited by rejoicing crowds and Otello’s wife, Desdemona. Iago,

supposedly a close friend of Otello, feels himself he has been

passed over and demoted by the promotion of Cassio to Captain and

Otello’s deputy. He resolves to revenge himself on the Moor, whom he

secretly hates, and weaves a deadly intrigue. Exploiting the desires

and weaknesses of the people surrounding him, he throws suspicion on

Desdemona that she has been unfaithful, driving an irredeemable

wedge between her and Otello. Having escaped from natural forces in

Act I, Otello is defeated by the storms of his own mind. When

several factors seem to suggest that Cassio and Desdemona are having

an affair, Otello strangles the woman whom he loves. For no cause,

as is quickly shown. Otello faces the consequences and stabs himself

to death.

|

|

|

||||

| Human Warehouse

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

José Cura is the epitome of Otello. So we journeyed to Berlin to see the greatest Otello sing in a production we have been told was (a) awful or (b) wonderful. Which would it be? I think it all comes down to suspension: there was much novel and intriguing in the director’s vision, but it required a whole lot of ignoring both Verdi and Shakespeare to accept Kriegenburg's version. Here we go: Act 1: There were 69 (?) beds on stage. All stacked. And a TV screen in each sleeping area. After the first ten minutes, these were rendered useless and never used again. Now that requires a real suspension: no one would find escape from the camp by watching a movie or favorite TV show? And if centrally controlled (and nothing in the production would indicate any sort of mind control), wouldn’t the powers that be want to stupefy the crowd with mindless entertainment? Alas.

Each sleeping area had one or two people in them. That's a lot of people to have on stage. Even if they're stacked vertically. And then there were the phantom wanderers who would drift in and across, until someone would grab them and lead them away. Time after time. Otello emerges from the crowd to sing Esultate almost as an afterthought—a less magnetic actor would have been totally lost but of course Cura just pulls the audience into his performance. After Otello goes off with Desdemona and Emilia in tow, a desk in dragged on stage and Cassio gets situated. Yosep Kang, who plays Cassio, is an attractive lyric tenor who brought an innocent intensity to the role. As he gets pressured by Iago and Rodrigo, he gets drunk and things get out of control; the plethora of people on stage begins throwing paper balls at him. That's a lot of garbage. And no one ever did a very good job cleaning up the mess before the love duet. To create some sort of privacy, a divider with an alcove bed came down blocking out the rest of the world. Separating them from the outside. Act 2: Iago's credo wasn't bad. Very nice, strong voice; however, the way Zeljko Lucic went about poking and prodding Otello, trying to dredge up the hidden insecurities, reminded me of Mad-Eye Moody from Harry Potter—way over the top.

Otello's fits of rage and inability to control his emotions made for interesting beatings towards the stage props--desk being upturned, chairs being thrown, water being spilled all over the stage, pictures being lit on fire with the fire marshal waiting nervously in the wings. Desdemona and Otello interacted well, even when he was slowly spiraling into insanity. *Side note* The dancers in the back were, in a strained way, portraying a more extreme story of Otello. They're together, but she leaves. Wondering, he goes to look for her and sees her with another man. She and the man dance. They share a coat. The other is there, watching. Act 3: Throughout the opera, there was an adorable little girl who is always involved in the action. After Iago's made Otello borderline crazy and Desdemona seemed never able to take a hint, she gently pats his head as he gasps and sobs as no other Otello can. It is a wonderful moment. The children were, in fact often useful if you don’t mind a little manipulation. While Iago was goading on Cassio, Otello hides among the children's chorus. They also snatch the handkerchief from Cassio and scatter after the deed was done. The hankie has a life of its own, much more dominant in this production than in any other I have seen. After attacking Desdemona in front of Lodovico, Otello can be seen off to the side of the stage attempting to sooth his head with the handkerchief full of ice. When that doesn't help and he succumbs to the insanity; he collapses and begins to maniacally rip the handkerchief into strips. After, with a crazed facial expression, he begins to tie the strips together into one long string of scraps.

*Side note* The couple in the back can now be seen in the corner. For a time before the big crescendo, they simply go back and forth from each other; she dances some strange little awkward dance. Subtle movements of hesitation. During the big crescendo of the final song of the act, the guy places a bag over the woman's head, suffocating her as Otello's world crashes around him. After she stops struggling, he holds her until curtain. Act 4: Desdemona begins the act by throwing her earrings into the water bowl. OK. Why? Her Willow Song is good. After she's asleep, Otello comes in, notices the earrings, throws them back into the water bowl. Why? Then takes off his jacket and takes his gun out of the holster. After Desdemona wakes up, he ties her hands together with the strips of the handkerchief that have been soaked (someone wanna explain the water theme?). With her hands tied around the bed post, Otello uses that for her execution. Squeezing her neck into the bed post, Desdemona dies. Emilia arrives to rouse the forces; she grabs the gun and threatens to shoot her husband, but Otello stops her by taking the gun. Emilia encourages him to do the deed but he hesitates and Iago simply walks up to him, shoves the gun aside, and walks off the stage. No one tries to stop him or go after him. Otello knows it is all over, takes his gun and a pillow, shoots himself, and snuggles up to Desdemona so both die in a seated position. That was pretty cool. So, how was it? The production wasn’t scandalous or outrageous, but neither was it a meaningful re-imagination of the story. It was a personal vision by the director imposed on a story that wasn’t meant to head that direction. There were several innovative ideas but as a whole, the opera really came alive only when the war is hell theme lifted at the start of Act III and the real story of Otello took center place. The singing actors were fabulous, and of course the most fabulous of all was José Cura. He didn’t just sing the role; he lived it. Anja Harteros was vocally wonderful but reticent as Desdemona, a little bit on the cool side, though her Act IV arias left few dry eyes in the auditorium. Zeljko Lucic sang well but was cartoonish in his actions, which made the fact no one could see through his evilness a bit unbelievable. So, all in all, a great Otello!

|

|

The Tale of Two Operas – Otello in

Berlin

Another View of the Berlin Otello

Director Andreas Kriegenburg has a lot

to say about war, it’s immediate and long-term effects on

perpetrator and victim, the fundamental inhumanity of taking up arms

against another for reasons unknown, the violence that haunts all

who touch or are touched by battle, the mental and emotional baggage

that casts shadows eternal. Those views were front and center in

his staging of Otello at the Deutsche Oper in Berlin:

he offered two operas in one, the first a red hot indictment against

war generic, the second a shoe-horning of the great Verdi tragedy

into the director’s vision. The first fills the stage with hollow

shells of men, women and children displaced by the war, the second

with military men who plot siege and destruction against the

ultimate strategic target – Desdemona.

Kriegenburg demands extreme suspension of disbelief: Forget natives

watching anxiously as the triumphant fleet battles wind and wave to

land after routing the Turks and saving the commonwealth; don’t

think of the cheers of the grateful citizenry when the heroic

general clamors down the gangplank and into the arms of his waiting

wife: Kriegenburg has a different vision. The isolated island

saved from invasion is replaced by a refugee camp, filled with those

who have fled the battle ground for the relative safety of a

temporary city made of bunks and boredom. For those trapped between

ravages of war and mundane safety, Otello’s return is but a

momentary diversion in the monotony of existence.

Forget the island of Cyprus and its isolated, claustrophobic

milieu. Wherever Kriegenburg places his drama, it appears to be a

landlocked, barren, primitive area, the battle waged with tanks and

guns and missiles, the antiseptic, anonymous carnage of twenty-first

century warfare broadcast in high definition for those who care to

watch. We know this because each cubicle has a television

installed, and during the opening the refugees huddle in their bunks

to watch the bombs explode and the tanks roar over arid terrain.

The screens show no evidence of victory—war is an endless horror;

instead they simply go black when Otello arrives exultant. The

cries of relief that the general is safe ring hollow: was he ever

in danger? In Verdi, the crowd witnesses man against indomitable

nature and measures the greatness of its leader not only in his

defeat of the common enemy but in his conquering of the cosmic

storm. In Kriegenburg’s modern world of warfare, generals delegate

operations and work strategic battle plans thousands of miles from

the front, never experiencing confrontation with mortality, never

personally handling a weapon, never seeing firsthand the bloodshed

they cause.

Forget the limitations imposed by a pre-electronic time period.

This is a modern event, complete with cable news feeds and

charitable giving of clothing by those lucky enough to be removed

from the violence. But this modernity has limits: once the war

ends, no one, not even the children, turns on the TV to watch

escapist fare and to live vicariously through the lives of actors.

There are no phones, no computers, no cell phones, no radios. It’s

as if the successful conclusion of the war throws the community

backwards 100 years, strips them of the every tool and every device

that allows the twin development of mass communication and mass

destruction to become commonplace.

Forget also the meme of minority angst, unless one counts the

awkward break in the forth wall when the curtain rises prior to Act

I and a handful of men, women, and children step forward in silence

to smudge their faces with black—was it a subtle message that we are

all one regardless of skin, or an almost embarrassingly transparent

nod to both Shakespeare and Verdi from a director who avoids core

themes for his war-is-hell vision? Ignore as well the lack of

reference to religion. Kriegenburg’s Otello succumbs not to the

madness of his color or the conflict inherent between his new and

old faith or even to the disabling bouts of epilepsy or his long

history of selling his soul to the highest bidder, but to the post

traumatic stress: in the end, Otello murders Desdemona because she

is the final enemy in the country of his diseased soldier’s mind.

The Stage:

Harald Thor presents a refugee camp established within a building,

with bunks lining the back of the stage, seven rows high, ten

columns wide, a hive of ceaseless activity. Suitcases announcing

the temporary nature of the refugees’ stay decorate the top row. The

triangle shape is broken in the corner by the filthy washroom

composed of three sinks and split with three ladders that run from

the floor to the top. Each bunk has a curtain but Acts I and II

play out in front of the masses. Each cubicle holds between one and

three refugees; each contains a mattress, blanket, and television.

Although the TV sets remain off after the opening victory, activity,

mostly mundane and repetitive, is constant: one young man builds

card houses; a trio play cat’s cradle endlessly; one folds a

seemingly endless supply of blankets with excruciating precision; a

man mindlessly massages his mate top to bottom, back to front. A

couple kisses and kiss again. Someone reads. A mother nurses; a

couple fights; a young woman changes shirts and skirts. Few ever

leave the bunks or change activity. Soldiers climb the ladders to

no purpose, then climb down and disappear. Periodically, female

refugees climb a few rungs and sway in synchronicity to the music.

One set of bunks jut into the open stage at the midway point; it is

filled with people, mainly children. The stage proper is littered

with refugees, mostly hoards of children and a few lost souls who

wander aimlessly, innocent victims of the ravages of war. A

pregnant woman massages her belly and seems in perpetual labor but

never gives birth. On occasion, a black-clad woman dances stage

left while her navy-clad lover watches in growing dismay and anger.

Two stuffed grey leather chairs and small table are featured stage

right, with Iago and Rodrigo in residence as the crowd sings. Stage

left, Desdemona and Emilia sit unmoving on suitcases, backs to the

audience, new refugees destined to be marked by the unstoppable

violence of war.

At strategic moments, a desk and chair are moved into place stage

left, where first Cassio and then Otello conduct business.

The only exception to the busy stagecraft of the refugee camp is the

Act I love duet and the totality of Act IV, when the bunks are

obscured with the austere bedroom of Otello and Desdemona: dark wood

paneling, a brightly lit double bed with white coverlet, and a

companion spotlighted wash basin.

Costumes:

Andrea Schraad offers modern rag-bag chic as the operative meme in

dressing the crowd. The children are dressed in casual apparel that

one could find on the streets of most modern cities. Otello wears

(and frequently takes off) his long outerwear military coat; Emilia

wears the same dress throughout the opera; Desdemona wears the same

blue long-waist dress and black heels until Act IV when she is

dressed alternatively in her wedding gown and her night gown: does

time simply cease to advance in this refugee camp?

Questions We Still Puzzle Over:

Water. Water of life, baptism, washing away of sins, purity,

birth or rebirth, the crossing over from life to death—water can

symbolize a host of concepts. In this production, the bedroom basin

is bathed in light; in Act I, Otello and Desdemona sensually wash

each other, with Desdemona using her dampened strawberry-covered

handkerchief to caress her husband; in Act II, Desdemona pours

bottled water on her hankie to placate her spouse. Later, in Act

III, Otello pours ice cubes into the hankie to cool his brow and

neck after he attacks Desdemona. In the last Act, Desdemona tosses

her earrings into the basin, Otello first digs them out and then

tosses them back in before soaking the remnants of the hankie and

then wringing it out. Water is a recurrent theme, emphasized in

each act, yet to what end? What is the purpose of constantly

drenching the symbol of fidelity in water? Why toss the earrings

in? Is it Desdemona denouncing the erotic to embrace the spiritual

in her final moments?

Clothes.

Otello arrives in full overcoat over shirt and suspenders, even

though all action takes place indoors and most of the officers

appear to be wearing the uniform of the day under the long coat.

Desdemona first appears in a coat, though Emilia does not. In the

love duet, long after she arrives, Desdemona finally takes of her

coat and puts it on the bed; Otello also takes his off and throws

it to the ground; Desdemona then picks it up and puts it on (either

in an attempt to take on his burdens or to climb inside the skin of

her husband, to feel safe within the cocoon of his most obvious

persona, to smother herself in his scent and warmth). Later, after

some foreplay involving the two of them and the coat, Otello removes

it from Desdemona and lays it at her feet

(obviously laying all that he is at her disposal);

she walks across it to him. In later acts, the coat is on and then

off, seems to have a life of its own as it appears on the back of a

chair, then on the floor, then amidst the children. In Act IV,

Desdemona first appears in her wedding gown, takes it off for the

Willow Song, then puts it back on for Ave Maria. Otello arrives in

his short officer’s jacket with holster, the first time he has worn

it; he immediately pulls it off and dumps it on the floor. And the

principles are not the only ones who invest time and energy in the

nuances of garments: extras kept changing clothes as well,

especially one woman in a cubicle who does nothing else throughout

the opera but put on and take off clothes.

Dance.

Why the pantomime of the tragedy ‘danced’ in the background? The

stories are not identical, since the man witnesses the infidelity

but it proved more of a distraction than an illumination. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Concert: Ceský Krumlov

"Maestro Cura was spectacular! Thank you many times."

President Vaclav Klaus

"Perfume" of the words important, says star of Český Krumlov International Music Festival Jose Cura

16-07-2010 13:01

Ian Willoughby

The Argentinean singer Jose Cura is one of the biggest stars of contemporary opera, known for his powerful and distinctive interpretations of characters like Verdi’s Otello. Czech fans will have a rare chance to see him in the flesh this weekend, when he performs two concerts at the International Music Festival in Český Krumlov, one of the country’s most beautiful towns.

I spoke to Jose Cura in Prague earlier this week, just before he set off for south Bohemia. Given his famed skills as an actor, does he give preference to operas with relatively strong narratives?

“Of course, of course. I feel very embarrassed when I have to do operas with a…silly libretto. Even when the music is good. For example, [Verdi’s] Il Trovatore is a great, great piece of music, but the libretto is so, so…funny sometimes that it is very difficult sometimes to feel comfortable on stage.

“I did Trovatore and there is a DVD of my Trovatore, etc, etc. But it’s a role I don’t do any more now, because I really didn’t feel happy on stage with it. But this is only an example.”

Is your interest in acting also a reason you don’t like singing phonetically?

“Of course, yes. When you are an honest actor on stage, you know that the most important thing is not only the words, but the perfume of the words, what is behind, under and around the words, what is not written exactly.

“If you don’t speak the language very, very well, if you don’t master the language, unless you think in the language, pray in the language, you cannot say that language belongs to you.

“That’s why I don’t sing in German for example. I am sure I would probably do a more or less good thing vocally, but I am sure that I would not be very happy with my dramatic interpretation. I don’t want to feel unhappy on stage, because then people will feel it.”

Generally speaking, opera stars are expected to be able to act more today than they would have been in the past. Why has that change come about?

“It’s very simple. In the past – I’m talking about a long time ago – when cinema was in the beginning, when going to the theatre was for a very small group of people, of course we didn’t have internet, we didn’t have TV, we didn’t have any of these things, it was easy to be on stage doing little things, almost nothing, because the people were there to enjoy the music.

“Now, if you only want to enjoy the music you stay home, you put on a CD, and that’s it. If you come to the theatre with the background of…everybody knows a good movie, everybody understands when a movie is good or bad, when an actor is good or bad.

“When you watch TV you know if you are watching garbage or a good show. If you like garbage, that’s another problem, but you understand…many things in the past were not so easy.

“So it’s impossible today to behave like in the past. Not because the past was bad, but because our present has a lot of different information. And the obligation of an artist is to live in the present.”

I guess also you must have to be physically fitter than your predecessors.

“Well, it’s expected. The problem with opera is that opera is a paradox. Of course the number one thing is the voice. If you don’t have the voice, even if you look very good, you can go home.

“And the contrary…if you have the voice and you don’t look good, that you can accept sometimes…Of course everybody would like to look like Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie – we would love it, but it’s not possible. But to look at least as good as you can, that is not impossible.”

What is your relationship to Czech music?

“As everybody knows I started my career almost with Janáček. I also did a recording of Dvořák’s Love Songs and the Ninth Symphony for the one hundredth anniversary in 2004. So far that’s my real link to Czech music, which is not big.

“Again, if I conduct then it’s OK, but when I sing, because I don’t speak Czech…it was very, very difficult to do the recording of the Love Songs for example. I did it at Czech Radio, by the way, in 2003. It was very, very difficult – it was a nightmare to try to convey the words of a language that is not mine.

“That’s why I wanted to do it in Prague here, because I was surrounded by Czech people…the technicians, everybody was Czech, so I was breathing in Czech.”