Turandot

Turin and Zurich Production

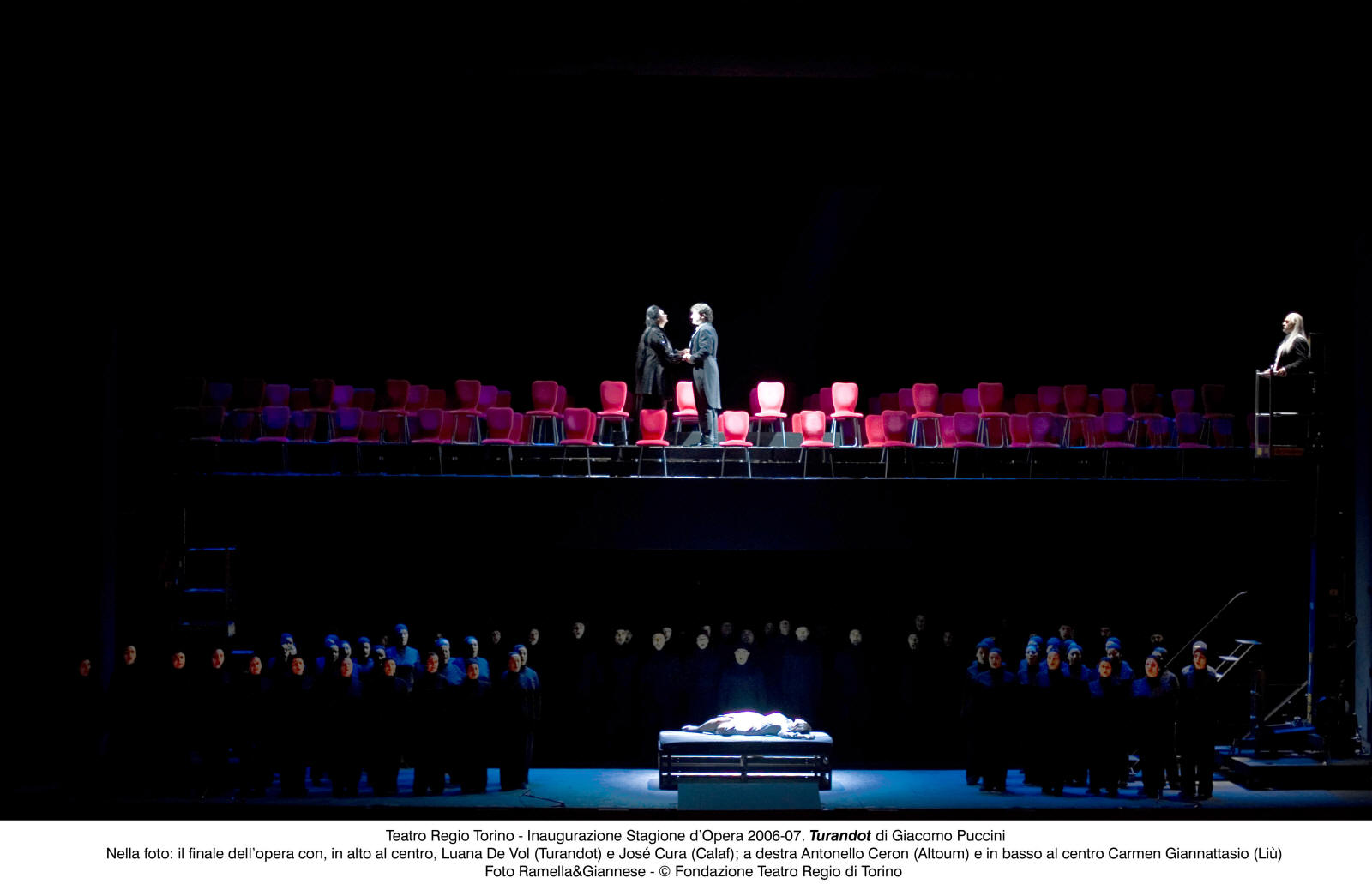

Turin - 2006

| In response to the severe economic conditions of 2005 which saw

the Italian government cut subsidies to opera-symphonic foundations,

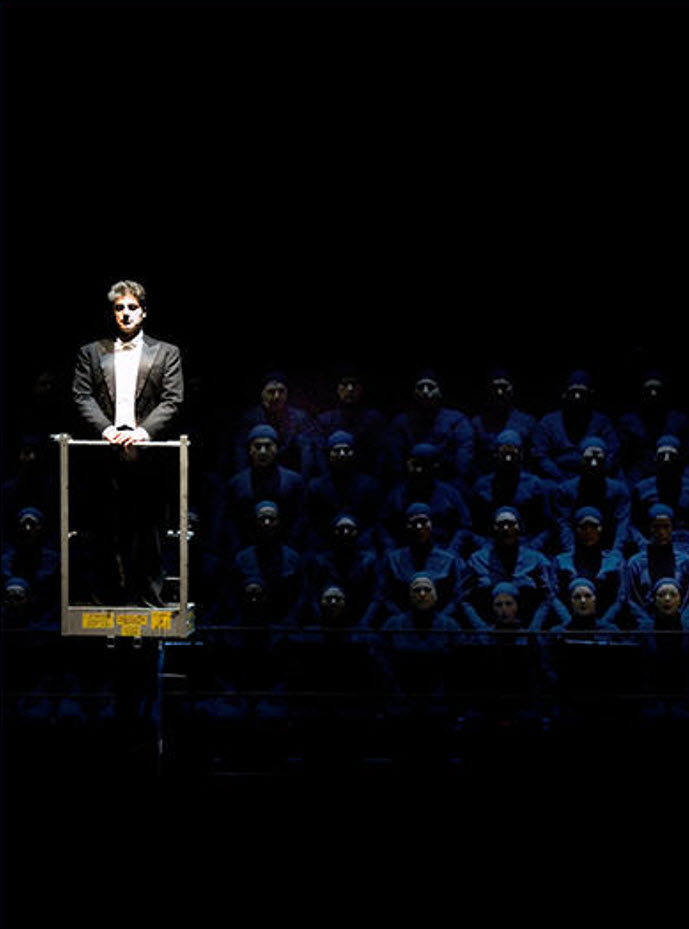

one theater took a creative approach to highlight the impact of fund

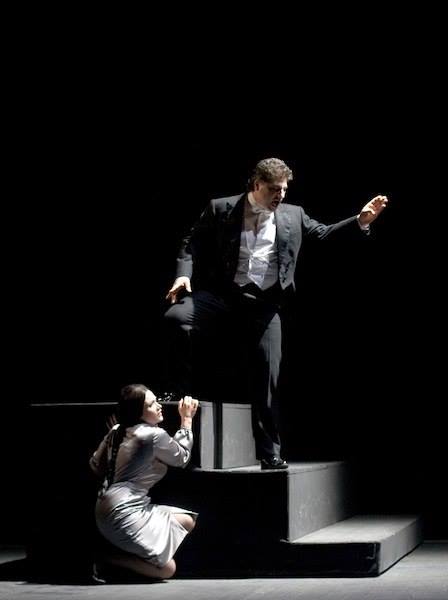

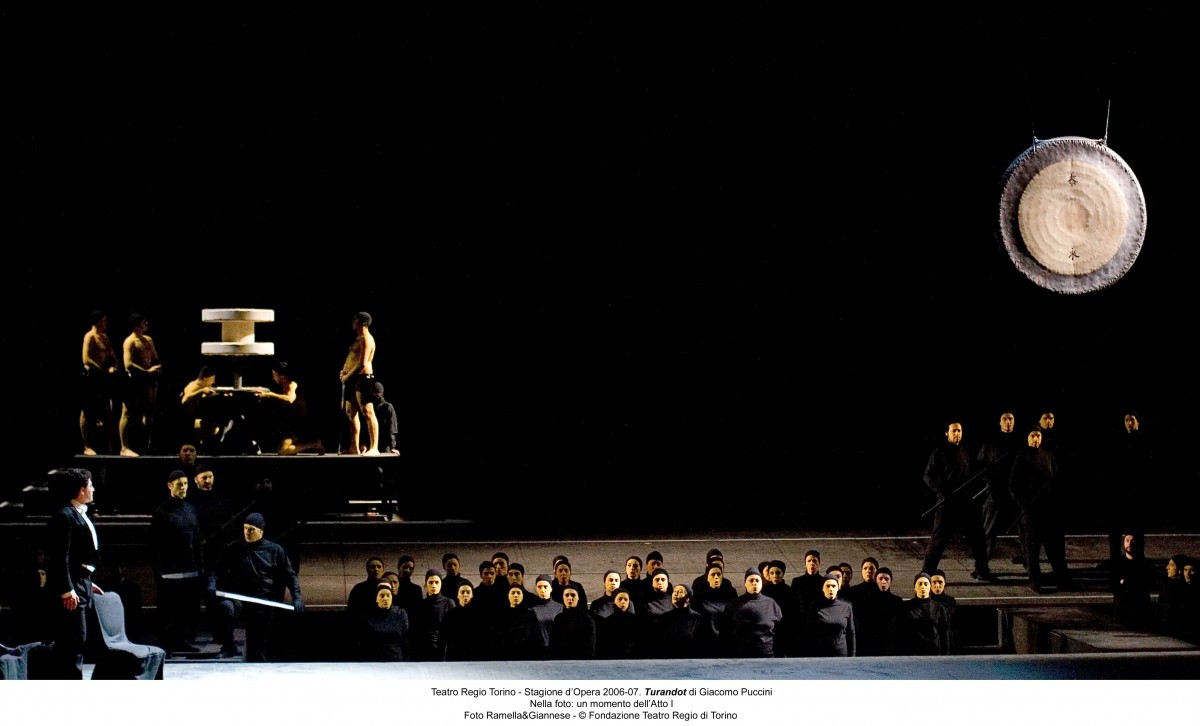

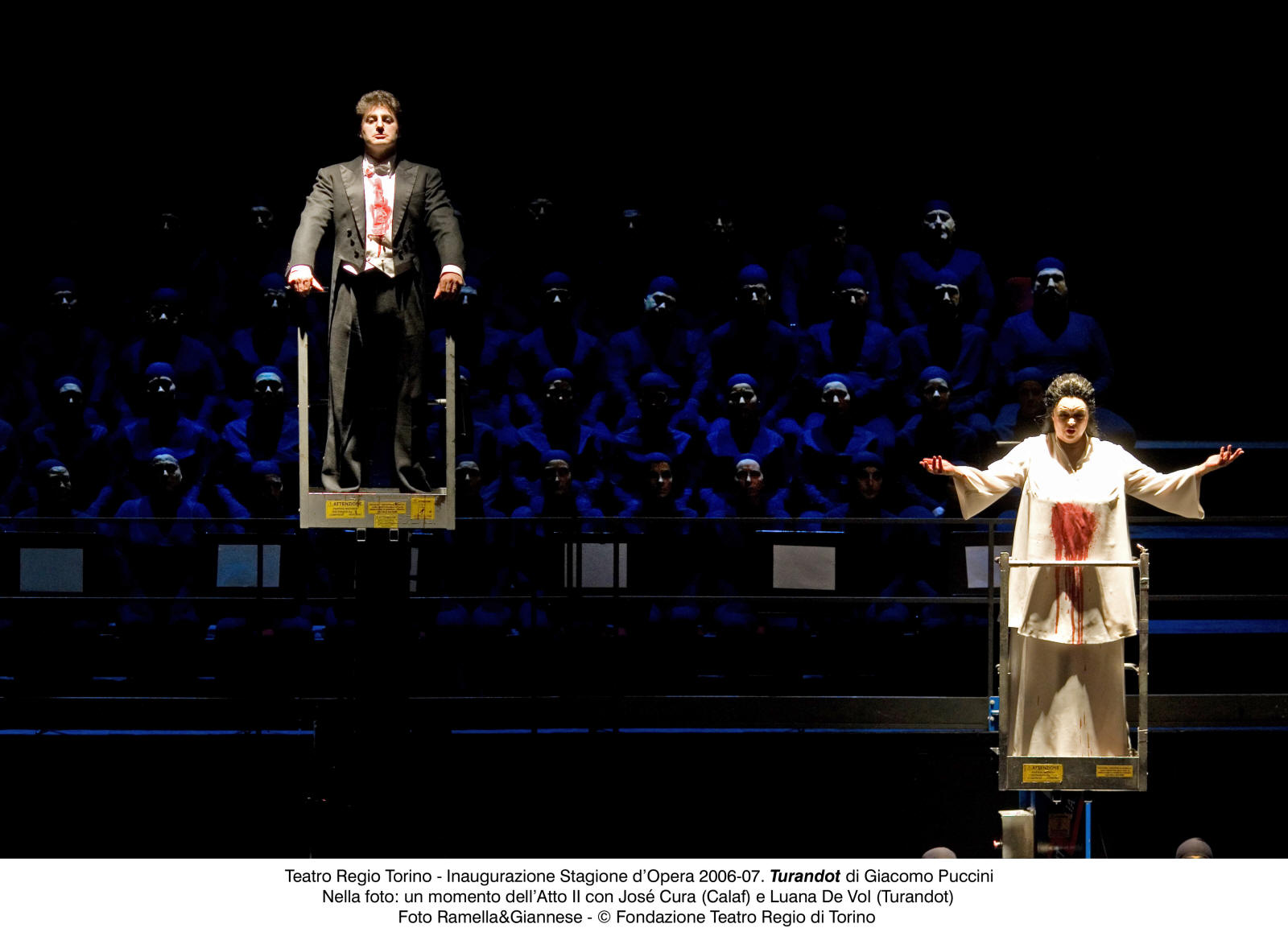

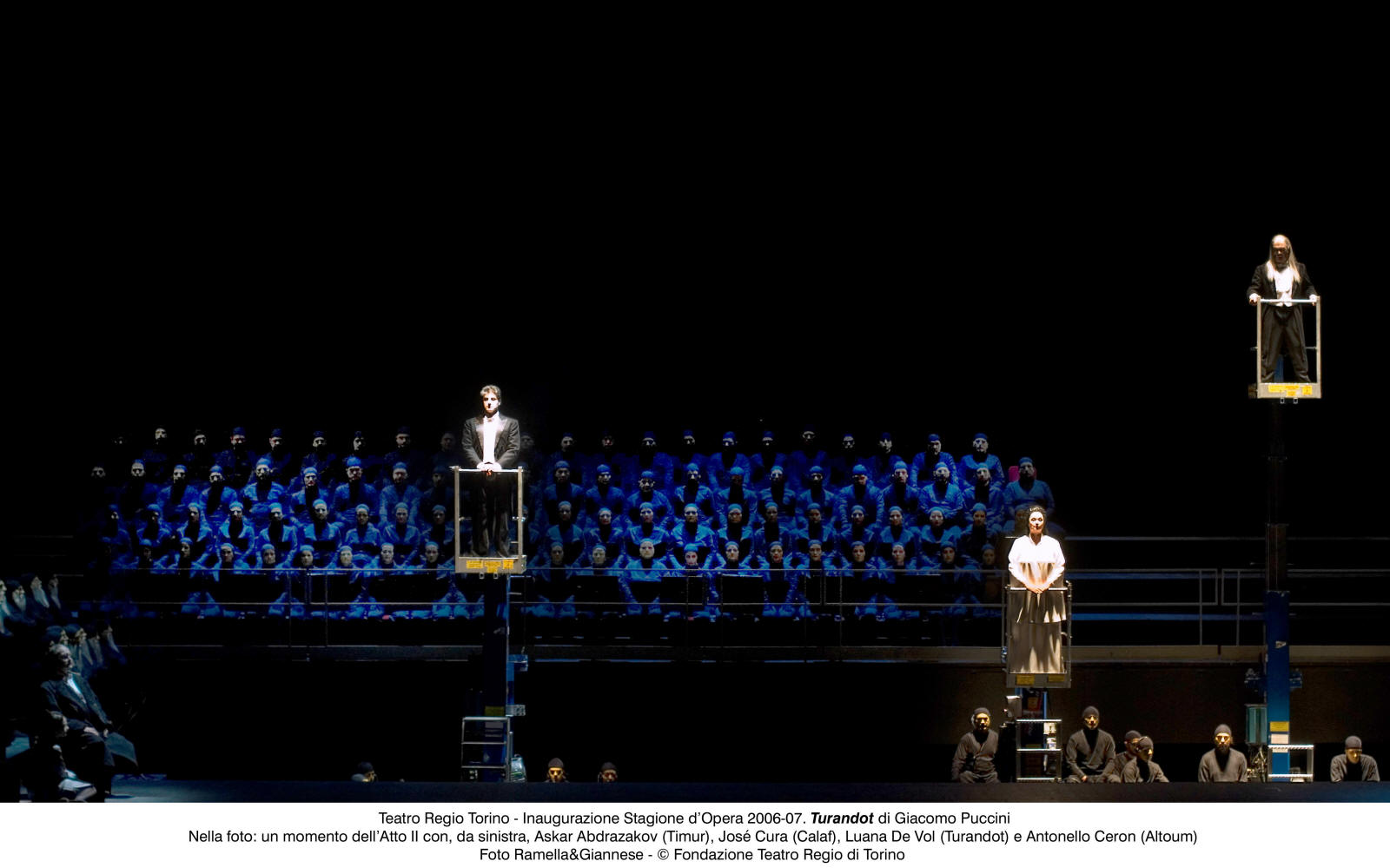

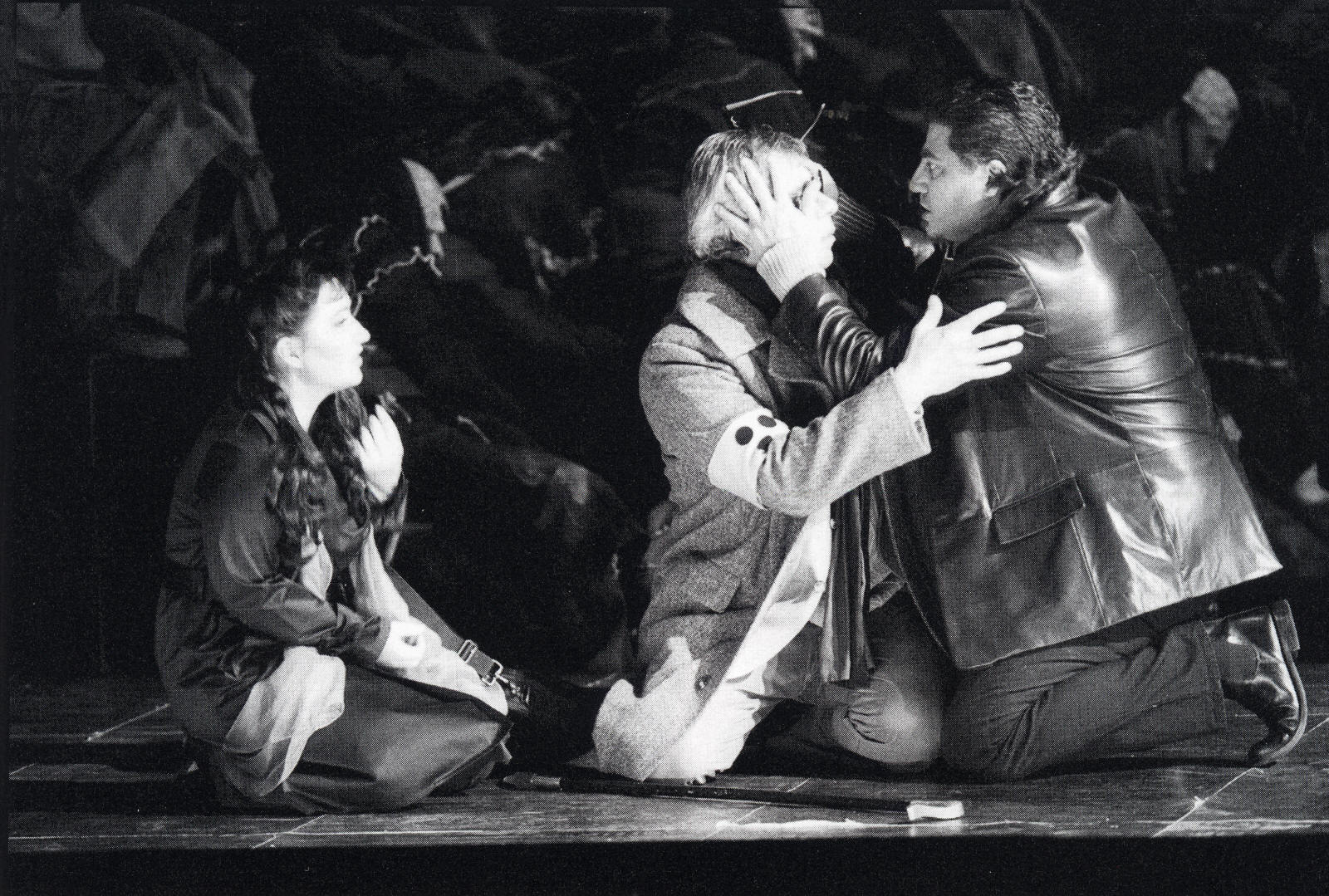

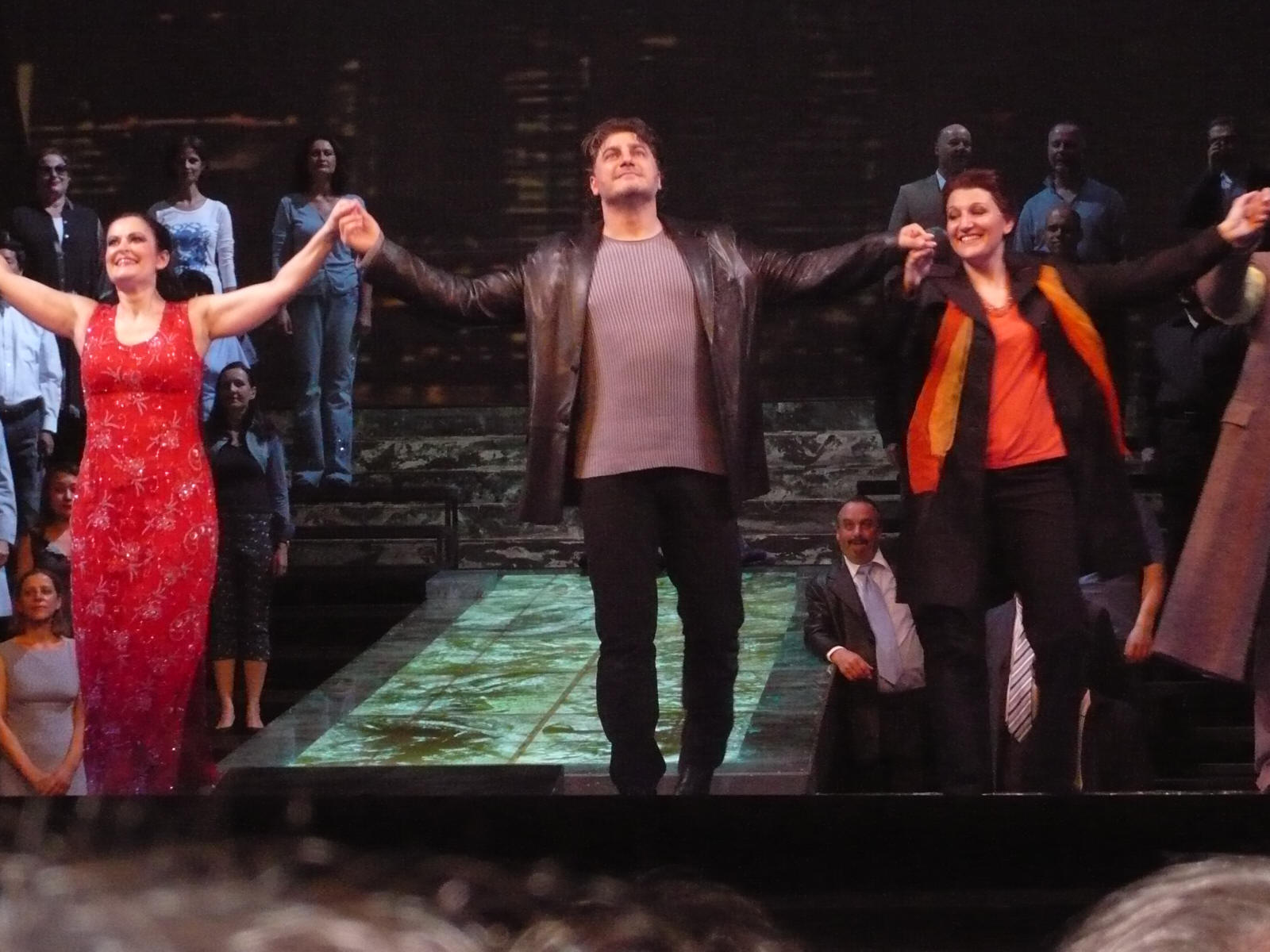

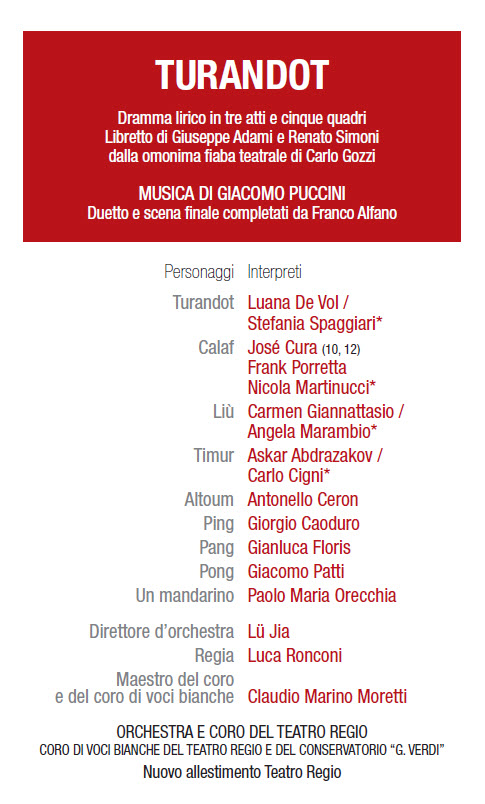

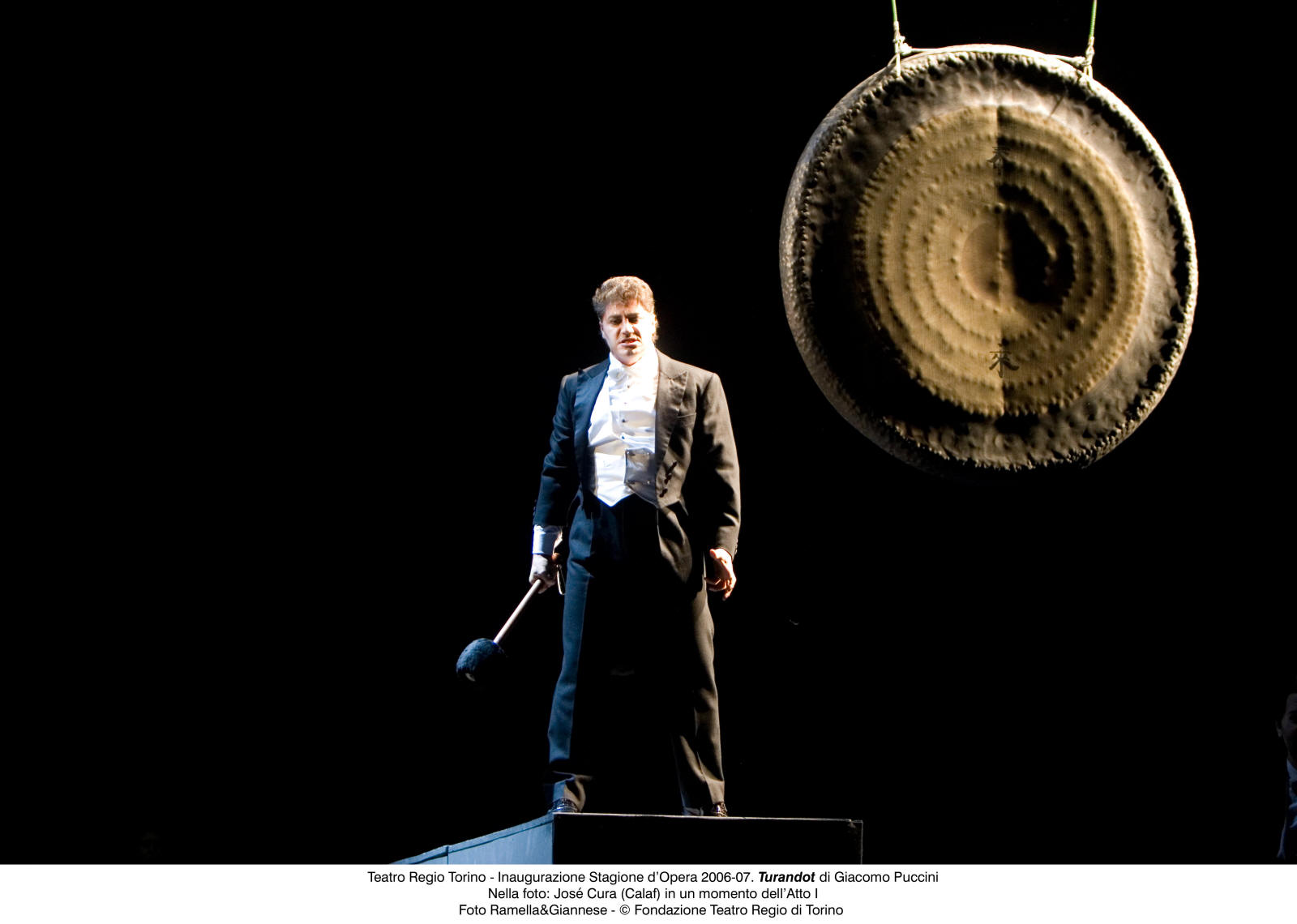

reduction. Turandot, which opened the Teatro Regio 2006/2007 season was presented in a deliberately "naked" staging to demonstrate the gravity of the economic situation. Luca Ronconi accepted the challenge of representing Turandot without traditional stage sets and costumes, pushing the creative effort of pure direction to the maximum. The director used existing technological and human to mount the opera: mobile bridges, forklifts and light effects were heavily used to create plays of volumes and the right atmospheres. The production also required a significant commitment from the performers (Luana De Vol, José Cura, Carmen Giannattasio and Askar Abdrazakov) who were called to a musical performance that was, if possible, even more intense than usual. |

|

Turandot essential and persuasive: Ronconi rediscovers the true Puccini Il Giornale Lorenzo Arruga 15 October 2006

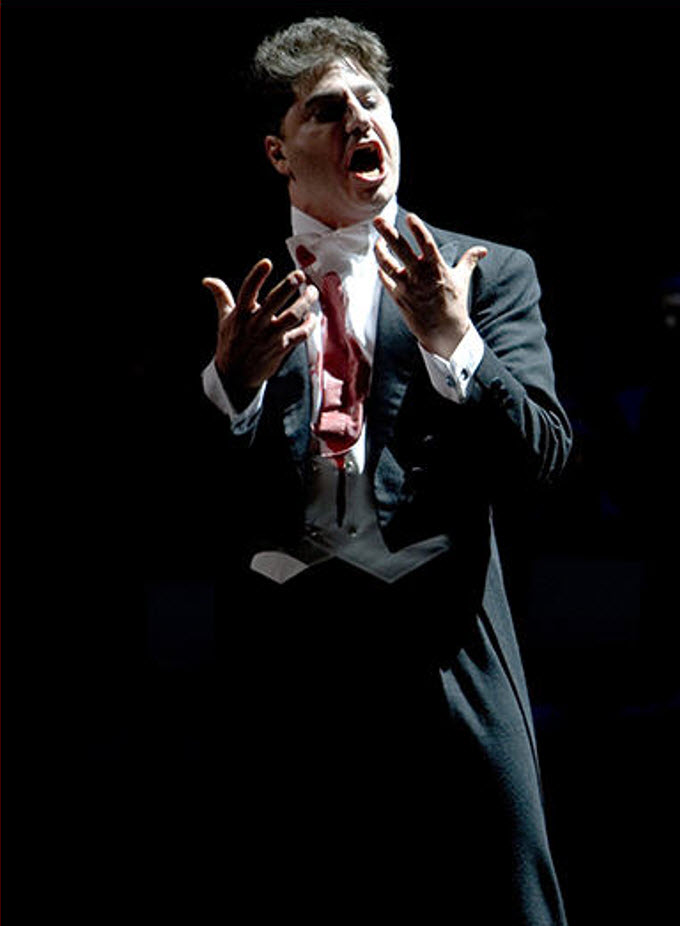

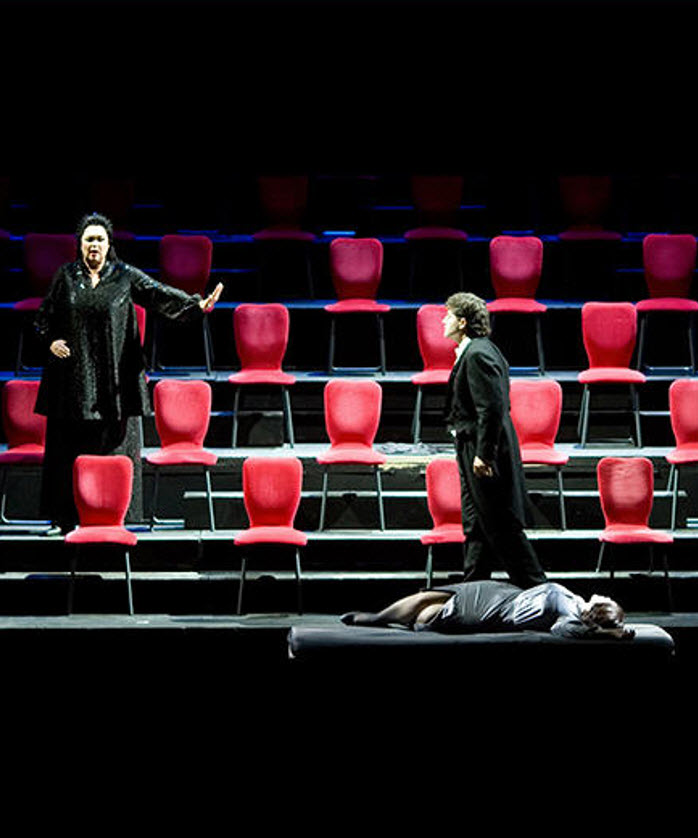

The season opening at the Teatro Regio in Turin was convincing and successful [Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpts] The most important event in theater these days is Turandot at the Teatro Regio in Turin. Not only because it is an extraordinary success, not only because it is the opening of a smart season, and not even only because of the idea, beautiful but more symbolic than exemplary, of presenting a show without the lavish sets that usually accompany this opera. It is important because one leaves enriched, with a desire to go to the theater more and with a profound curiosity to rethink Puccini and Turandot. There is an interesting company, with an unusual protagonist, Luana De Vol, committed not to thundering the beautiful big notes but to sculpting the words in a very sensitive phrasing; with a Liù, Carmen Giannattasio, who won over the public with her fascinating determination, and with a Prince Calaf in the person of José Cura, who attacks the notes without too many colors and with unnecessary darkening, but who has in his voice and presence a very rare authority; and with the other performers, even if not always vocally as we would like (especially Ping, Pong and Pang). There is an attentive and balanced director, Lü Jia, who overcomes well the discomfort of having to create a China so different from his own. Above all, there is the director Luca Ronconi. Turandot, as we know, is Puccini's last opera, which remained unfinished because his death arrived before he had resolved his doubts about the ending. It is the story of a cruel princess who, to avenge the rape of her ancestresses by a foreign conqueror, tests the suitors by asking them three riddles: she will marry whoever solves them but she will have the head chopped off of those who can’t. After many beheadings, a mysterious prince arrives from afar, answers correctly and then turns her rebellion to love. A static and ceremonial work, Turandot invokes both the spectacle of a fairy-tale and horrifying Beijing. Ronconi makes the spectacle flow from the naked, unsurpassed charm of the opera stage. Mobile bridges, trolleys, elevators, treadmills. But these work not as stunning effects but rather as cultural references to fix dramaturgical moments. The work is thoroughly investigated. There is nothing non-essential, the costumes themselves are perfunctory, as if chosen from a useful baggage for the rehearsals. But little by little the x-ray of the work becomes a language of images, marvelous for what they reveal, silhouetted in a measureless empty space. The understated gestures draw portraits: the prince absorbed in his destiny as a victor, the three listless ministers tired of their task as executioners, his faithful slave accustomed to submission who teaches everyone what love is in that arid and evil world. And above all Turandot. Ronconi wins the uncomfortable challenge of the non-Puccini ending, where the musician Alfano unintentionally transforms the happy ending into pages of kitsch and brings the cruel princess from hate to love. In the score, there is a big kiss, with the conversion coming very quickly through hormonal pathways. On stage, however, we experienced the psychological travail of her conquering, first unwillingly then alternatively dramatically, an early, complex womanhood of her own. Not triumphalism, but acceptance of a truth discovered within herself. An act of love for Puccini's distant hopes, an act of faith in theater that, laid bare, can suggest human truths.

|

|

|

|

Turandot

Opera Now Juliet Giraldi

What started out as a protest against the financial cuts to the performing arts by the last government became, in the hands of Luca Ronconi, an interesting challenge. He decided to produce a ‘budget Turandot’, without sets or costumes, having been forced to abandon the staging he had planned with Margherita Palli, his usual designer (apparently using a lot of bicycles).

I had therefore expected little more than a concert version of the opera – and a producer less able than Ronconi would have left it at that. Instead, he produced an extraordinary and thrilling Turandot, by simply playing with existing stage mechanisms of the theater: the moving floors and steps, the pulleys, railing, the seats of the choir and above all the lights, used to spectacular effect.

An impressive scene opened the opera: to the words “Gira la cote!’ the sharpening stone revolves and sparks fly as the long swords are prepared for the executioner. Then there is the ghoulish, white figure of the Prince of Persia, clad in loin cloth, strung up for torture. A rising spotlight represents the moon. The psychological battle between Turandot and Calaf is simply illustrated by the ascent and descent of the moving steps, indicating by their changing levels superiority or inferiority. The costumes were reduced to a minimum: the singers in black evening dress, the chorus in anonymous black tunics.

The general effect is to lift the opera out of its specific Chinese setting into a kind of universal limbo, leaving the music to expand in all its harsh, bleak cruelty. With Liù Jia on the rostrum, emphasising every small detail, especially of the percussion, and the orchestra in symbiosis with the interpretation, the result was a fascinating revelation of Puccini’s final operatic statement.

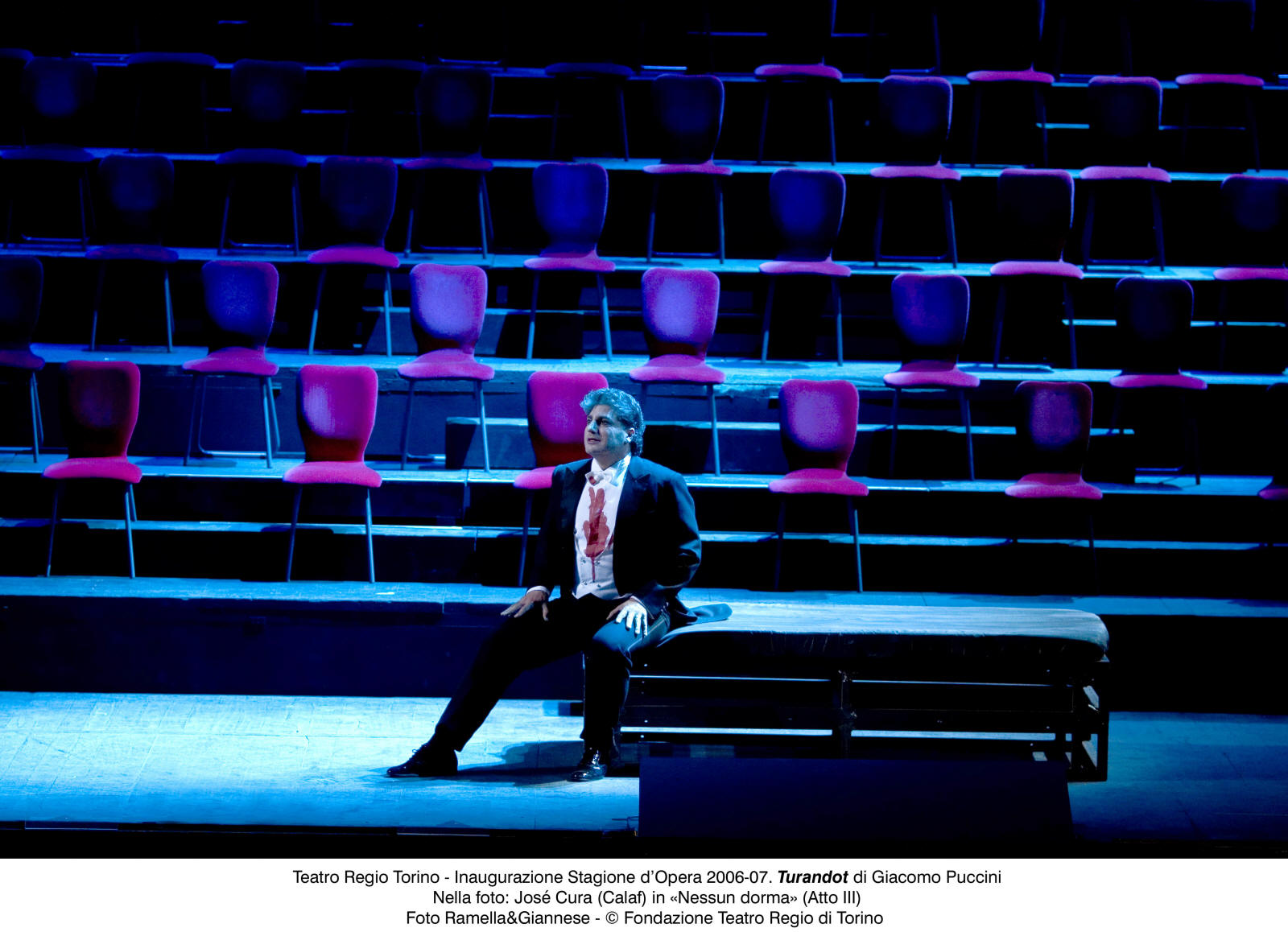

The opera was also well cast: Luana de Vol was a formidable Turandot, proud and unyielding to the last, in this ungratifying, shrill vocal part. José Cura, formal, severe, static even, but in keeping with the rest, using his voice with control and authority, especially in the riddle scene, and rising to the occasion in ‘Nessun dorma’ when he sits alone among the rows of empty (choir) seats. Liù, slightly hampered by her tight dress and heels, was interpreted by Carmen Giannostasio, and Timur by Askar Abdrazakov. The disenchanted trio, Ping, Pang and Pong, sung by Giorgio Caudoro, Giacomo Patti and Gianluca Floris, took up a novel pose: smooth-headed and in shirtsleeves the reminisce and philosophise, lying on leather couches and sucking tubes linked to oxygen cylinders. The audience was free to interpret this however it wished. |

|

Turandot

Trapsi Stefano Mola 11 October 2006

[Computer-Assisted Translation // Excerpt]

Let's say it now and then, later, try to explain it.

This production of Turandot is beautiful. Even nude (Ronconian adjective), without sets or costumes. A truly choral performance, in every sense. Of course, in the foreground are always the singers. But in this case, perhaps even more than at other times, it seems as if the whole theater is performing.

Let us take the first act. Baricco is right when he writes the pace of the narrative is drastically accelerated. “Everything is condensed into a handful of minutes: the Beijing of a thousand years ago, an angry mob [...], a young and beautiful prince who goes to his death, another prince who hides, an old man who recognizes him, and it is his father [... ], a slave girl who recognizes him, and it is this woman who will sacrifice her life for a smile [...]until the apparition of the red-hot core of that whole world, a woman [...] so beautiful that the nameless hero forgets his father, forgets the slave who loves him, forgets himself and challenges fate [...] [...] for death or that woman” (L'anima di Hegel e la mucche del Winsconsin, Garzanti). To be read like this, all in one breath. Like Puccini's music, a single fluid vein, where everything fits perfectly into its place, an overflowing torrent of restlessness, mystery, love, death, and so on.

The same (herein lies the genius of the staging) happens on the stage. The first act is movement. Pieces of stage lift, rotate, move, the dark mass of the chorus dressed in black shift, characters are united, separated, lifted. Functional movements, let's be clear. The impression is of being glued there, with ears and eyes. There is no time to think about the stage settings and costumes that are not there: we are inside a drama that is winding up like a terrible spring, so what does it matter if Calaf is in tails? While the chorus, this yes, is right to be black, this magma that first condemns and later moves, this dark depth of the soul that we are when we are crowd. The grotesque and melancholy scene with which the second act opens: Ping, Pong and Pang lying on three couches while smoking opium. Or when Act III opens, when it looks like a rerun of the theater in front of us, a tier filled with neat rows of red armchairs lit by a cold light, and in the middle, alone, Calaf. The notable thing is that in the staging there is no desire to amaze for the pure sake of doing so. The direction does not overlap with the work but tries, within the limits of the painfully imposed choice, to find a way to serve the music and the narrative. After all, a man alone on stage can already be theater alone, creating the world with a gesture: like a mime.

In this forced return to essentiality, Turandot finds its essence. Does it really matter that Turandot is in China? At the beginning of the libretto, we find these words: in China, in the time of fairy tales. But if it is the time of fairy tales, what matters is the word and how much the word does in our heads if we let it in. Turandot is ultimately the imperfect story of a conflict, between a feminine principle that in the memory of an ancient offense refuses contamination with the world, seeing in the masculine principle solely a desire to possess at any cost, and a masculine principle that starting from this desire to possess (Is Calaf really in love? And who believes that?) paradoxically brings Turandot back into the midst of the doubts with a violently passionate kiss. All this passing through a kind of ritual sacrifice, the death of Liù (perhaps the true dramatic peak of the opera), who in order to see the man she loves live sacrifices herself (not by chance, symbolically, her corpse remains on stage until the final duet included).

Turandot's world is a primal world, where impulses are instantaneous, where just a smile and a sudden appearance mark a day when the entire life alters, changing the course of rivers with a single gesture. After all, in the end, every love story perhaps must start from an incomprehensible flicker (is there such a thing as rational love?), and every choice, after all, is but a murder of the thousand other possible alternatives that a moment later fall away. In this sense, even without venturing too far down psychoanalytic path, Turandot is a powerfully archetypal affair, and it matters little to ask whether Turandot's surrender to Calaf is really believable, whether it is really narratively justified, explained, resolved by the ending that is after all Alfano's and which we will never know how Puccini would have wanted to write (not only from a musical point of view, but also dramaturgically, given the tormented correspondence with the librettists). If, therefore, we accept this perspective, being faced with an abstractly rarefied Turandot may fit. The fundamental thing, with costumes or without costumes, with sets or without sets, is that things be done well, that they have their own internal coherence: and this performance certainly does.

We come to the performers. Very high marks to José Cura. His Calaf is impetuous, at times rabid. He is extraordinary in Nessun dorma, an aria that often seems to be used as a mirror in which tenors admire their bravura. But what really is Nessun dorma? Nessun dorma because there is an edict from Turandot, the last gasp of her power. Nessun dorma because we must try to discover Calaf's identity. In the city, therefore, there is everything but tranquility and sweetness: rather, there is restlessness. And Calaf himself is anything but sweetness; rather he exudes the will to power: at dawn I will win. I will win Turandot: the conquest of a fortress, rather than a dream of love. In these notes, José Cura did not insert himself, he did not simply try to show off his voice, but to put that voice at the service of this determination, with a momentum in whose depths one almost glimpses a restrained anger. Equally high marks for Carmen Giannattasio, a sorrowful, passionate Liù, rendered with intensity and nuance. In Liù's death scene she reaches absolute emotional heights. Less convincing, in our humble opinion, is Luana De Vol's Turandot, who did not impress us either with her singing or with her slightly too stiff presence on the stage.

Convincing applause and appreciation for all and in a final note of appreciation we would like to thank the theater, the stage machines and to all those who operate them.

|

|

Turandot Opera Giorgio Guale March 2007 The Teatro Regio sprang back into action on October 10 with a Turandot stripped of any spectacle. Financial cuts meant that the theatre was faced with the choice of either reducing the production to a kind of concert performance or cancelling it altogether. They choose the former option, and persuaded Luca Ronconi (with appropriate remuneration) to run the risk of a flop. The result, in fact, was superb, thanks to the use of the Regio’s copious stage machinery and some wonderful lighting. A ‘spectacle’ was created that proved such a hit with the audience that the frankly routine singing and playing were ultimately overlooked. The Chinese conductor Lü Jia gave a balanced account of the score, apart from a few moments when he brought the orchestra up too loud, and the chorus, directed by Claudio Marino Moretti, was well-nigh flawless. Luana DeVol (at 64, a Turandot for the Guinness Book of Records ) tried her best to manage her reduced vocal resources, while as Liù, Carmen Giannattasio, despite her lack of expression, still managed to please the audience with her attractive, secure voice. But as Calaf, José Cura seem[ed] most concerned with winning the predictable round of applause after Nessun dorma.

|

Nessun dorma - 2006 Turin

|

Turandot in Turin Click on photos to watch |

|

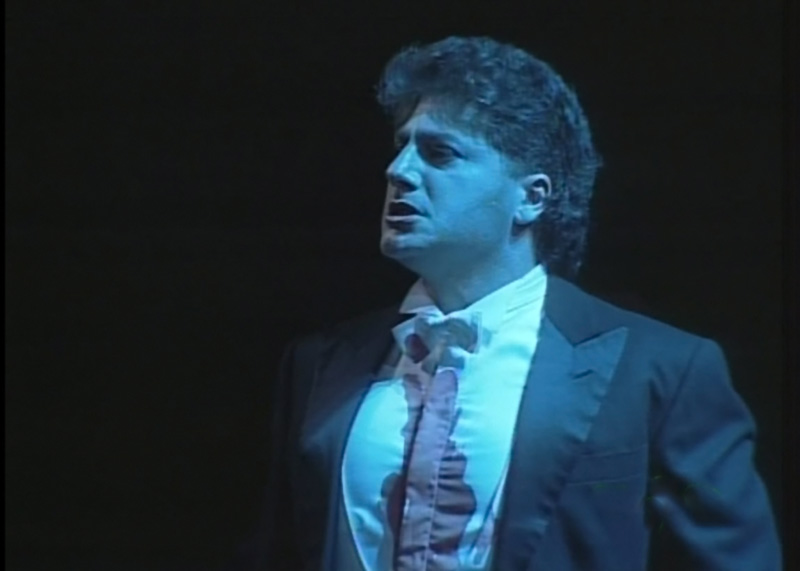

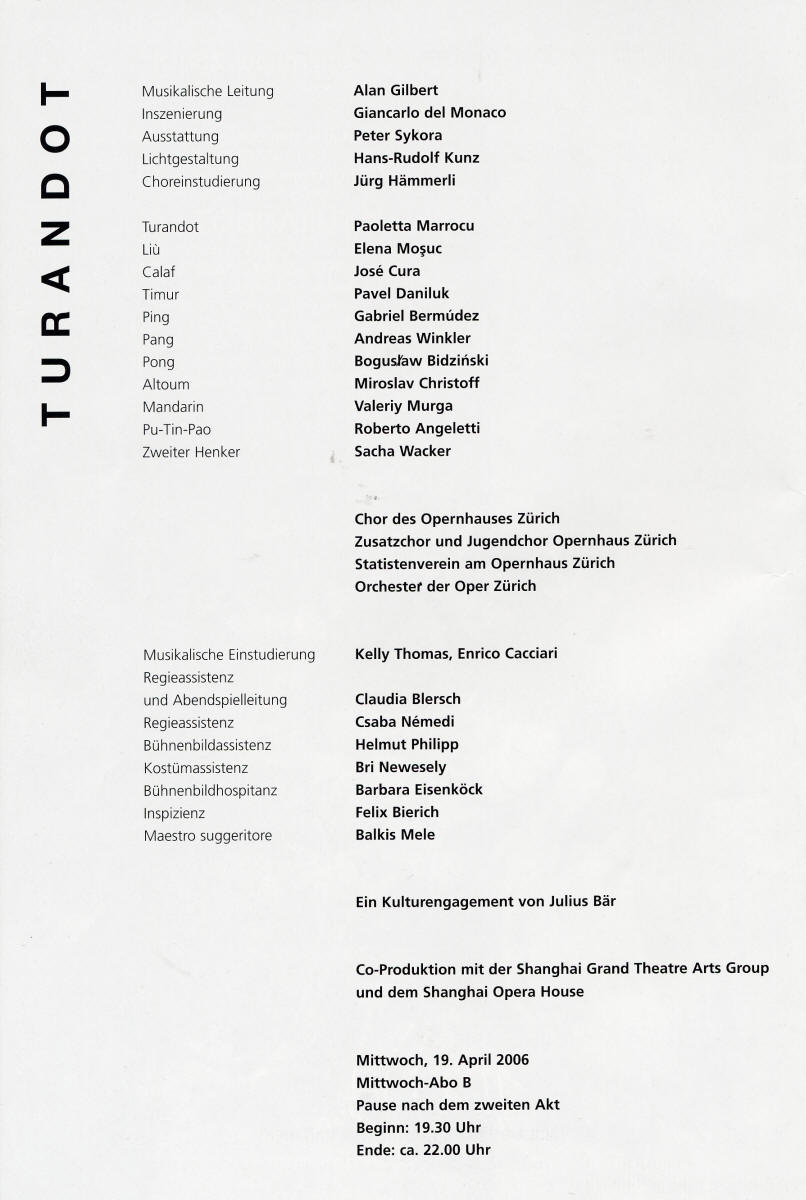

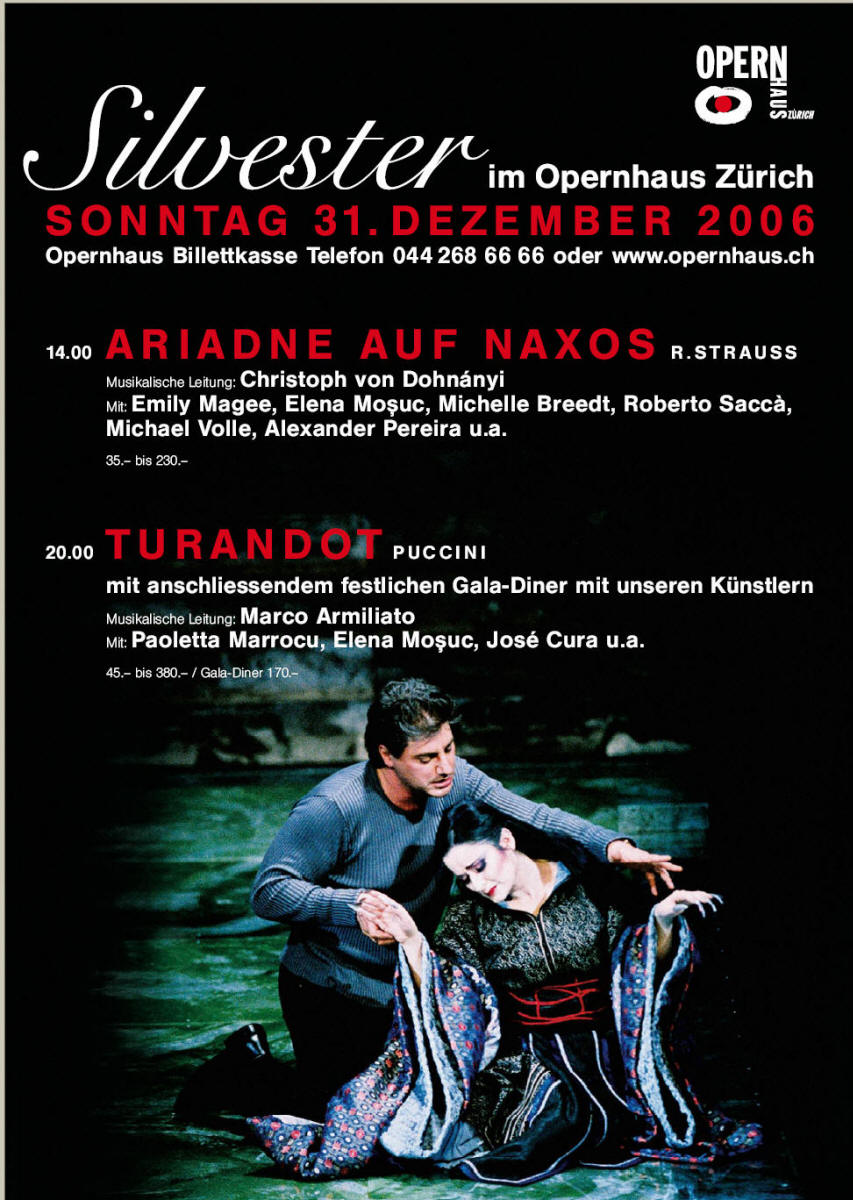

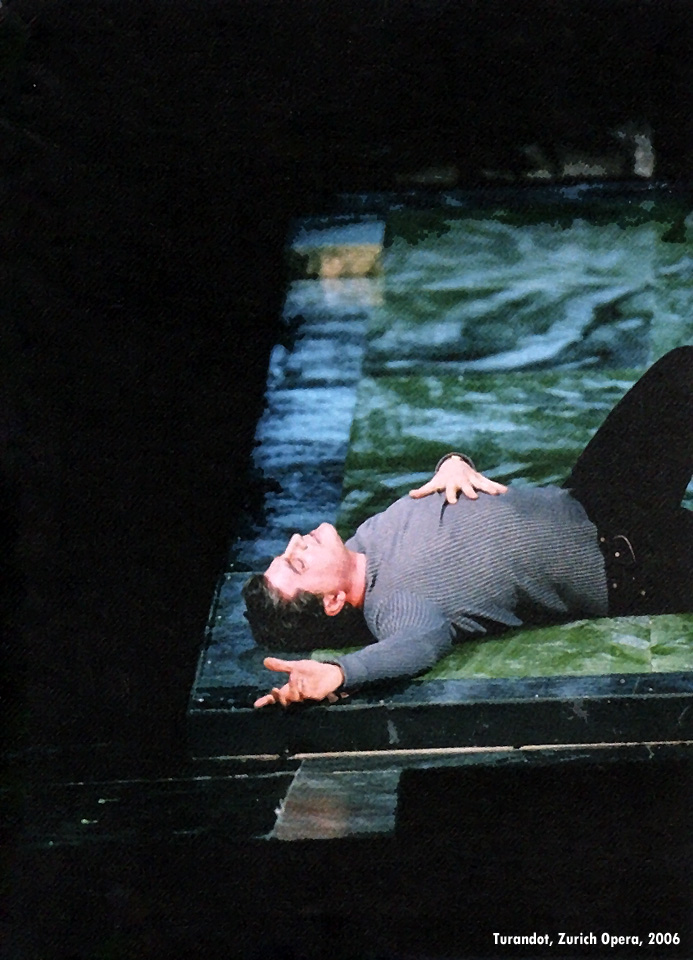

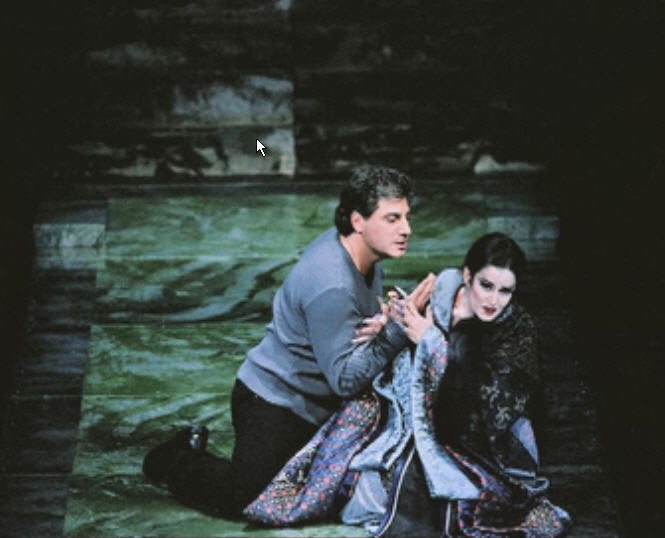

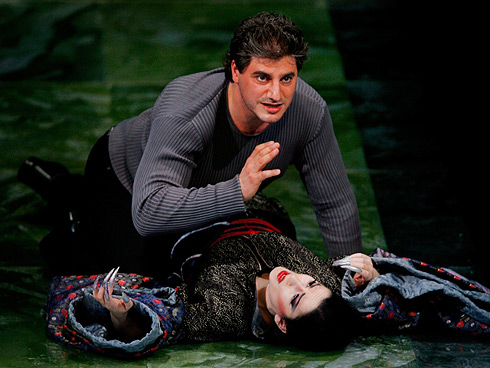

Zurich - 2006

|

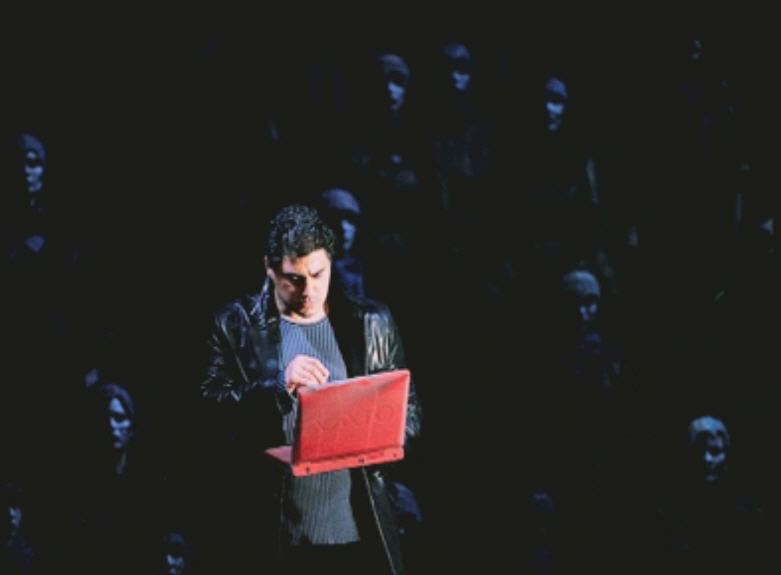

Turandot, Zürich, April 2006: “José Cura's Calaf was also brilliant. The creative "antics" that he displayed during a certain period has given way to a musically flawless interpretation. Sure, one could say that the voice still slips a little too much into the throat from time to time and that a little more attention should be paid to the vowel placement (especially in "Nessun dorma"), but at present no other tenor can so easily master this part. The bronze, baritonal voice coloration, paired with incredible expressive and vocal power and, when necessary, with velvety softness, sparked storms of enthusiasm. The nonchalance in his acting and the ease with which he took the high notes did the rest to make him the winner of the evening.” Vox Spectatricis, 4 October 2006

Turandot, Zürich, April 2006: “I had expected a generous and committed physical performance; I hadn’t anticipated an impeccable vocal one too. Cura can be an annoyingly wayward singer at times, but obviously found this production congenial and was on best behavior. A well-nigh perfect ‘Nessun dorma’ capped an exciting interpretation that played well to Cura’s ebullient Action Man strengths.” Opera Now, September / October 2006

Turandot, Zürich, April 2006: “It [was] easy for José Cura as Calaf to dominate the stage with his expansive presence. He takes advantage of it, as he sings ‘Nessun dorma’ while lying outstretched on his back. Although his darkly shaded tenor occasionally lives in a wild a marriage with the song phrases, he is convincing as an actor with a thrilling, daredevil approach. He has class. Much applause in the end, with storms of enthusiasm for everything - the audience liked the performance very much.” Zürichsee-Zeitung, 4 November 2006

Turandot, Zürich, April 2006: “Calaf (José Cura) delivers a great performance by being present throughout the story. His powerful tenor voice is particularly convincing in the striking passages. The Zurich audience nevertheless applauded frenetically at the end of the performance.” Kunstkritik, April 2006

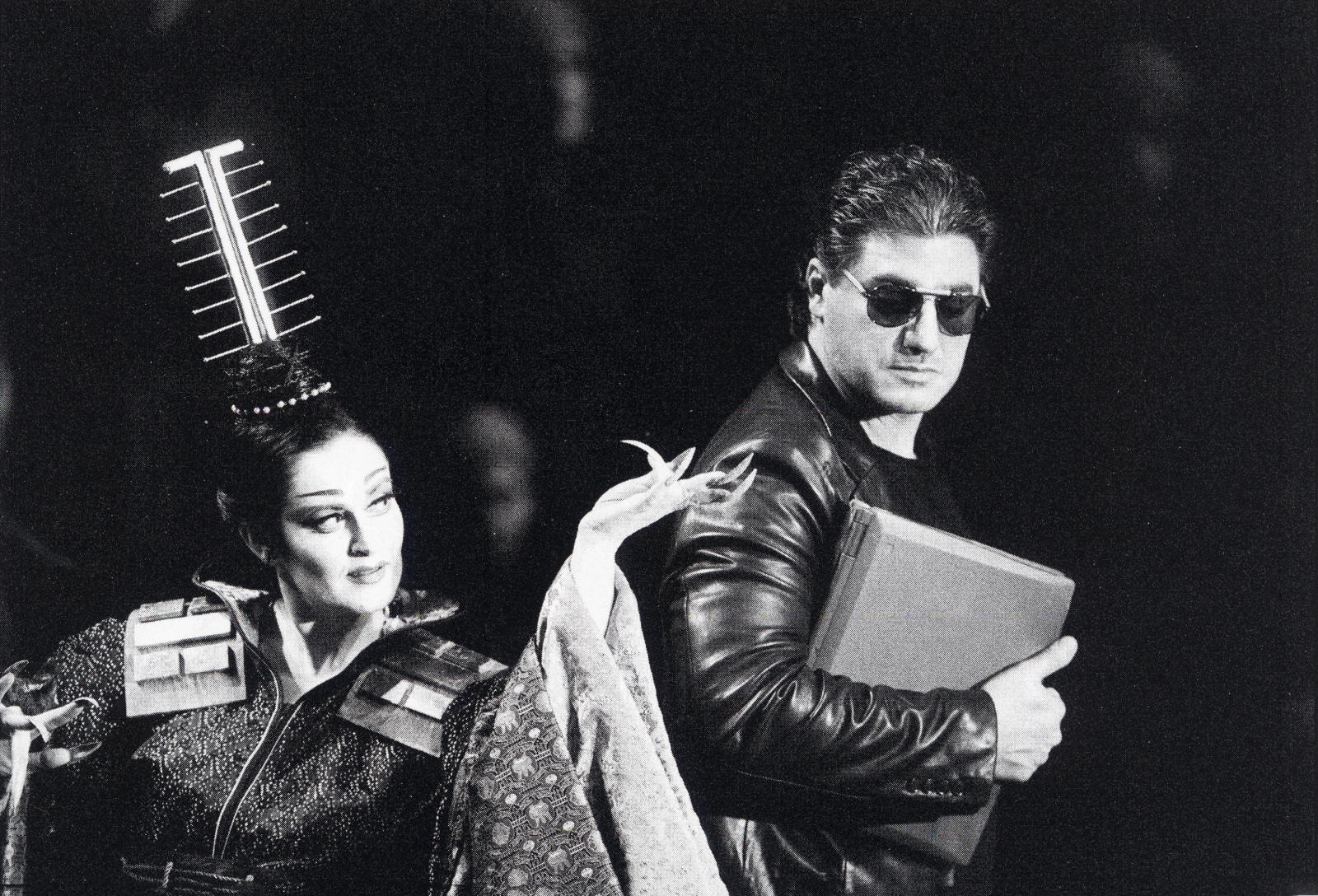

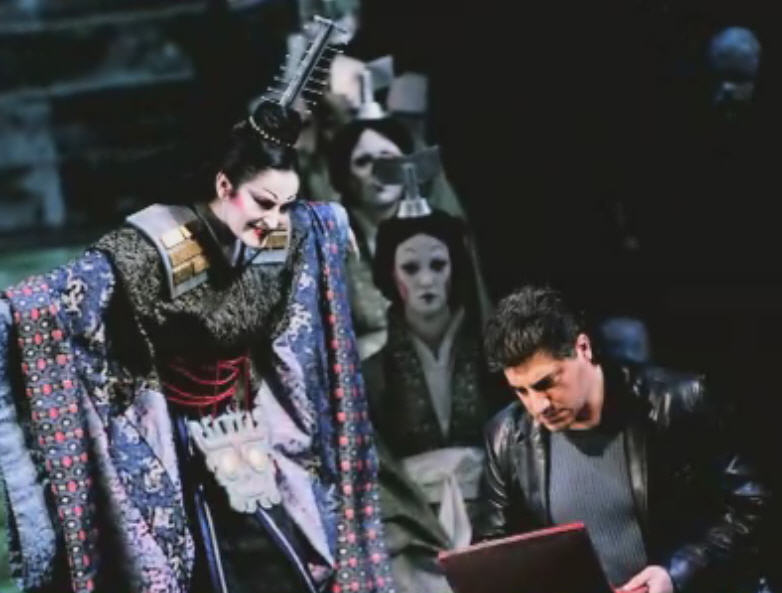

Turandot, Zürich, April 2006: “With so much pomp and circumstance, Del Monaco's portrayal of the characters remains superficial, with his focus mainly on Calaf, the unknown foreign prince who lands in the imperial palace as an alien. [Fortunately] the role of Calaf is a perfect match for José Cura and his dark tenor, which is more powerful and forceful than supple. He casually embodies the pure macho, who is not interested in love but in conquest and power. No cliché is spared, neither the black leather jacket nor the sunglasses and the bored reach for a cigarette when Emperor Altoum appears. In the end, not only does the princess change, freed from her ceremonial dress by Calaf, but her entire old kingdom bows to the culture of the foreigner. The premiere audience applauded vigorously.” NZZ, 11 April 2006

Turandot, Zürich, April 2006: “José Cura, the Argentinian star tenor, does justice to the macho and imposing demeanor that is undoubtedly inherent in the role and is impressively present at the climaxes with his full-bodied, dark tenor, which glistens powerfully at the top. He sings the hit Nessun dorma lying on his back, not as an isolated aria but as a transition between the orchestral introduction and the large choral scene that follows.” Neue Luzerner Zeitung, 11 April 2006

Turandot, Zürich, April 2006: “Giancarlo del Monaco's societal divide turns its back on the grandeur of the music, singing, costumes and sets. As the staging fails to live up to the tale, the music and its performers become irretrievably detached from it. It's as if we were watching two shows. The first with the pair Giancarlo del Monaco and José Cura, and the second with the music of Giacomo Puccini and its other performers. Tenor José Cura has no trouble integrating into this exercise. Is it a role of his personal design? Presenting himself as a macho whose ideology he seems to celebrate, he is odious, self-satisfied and vain to a fault. Vocally, too. Endowed with indisputable vocal means, the only artist on stage not making his debut in this opera, his performance is unworthy of a singer of his reputation. Constantly singing at the top volume of his voice, musically insensitive, forgetting the respect he owes to musicality so as not to cover his colleagues with his loud “have you seen me,” his diction is disastrous. The audience, however, gave a resounding thumbs-up to the production and Cura received a standing ovation….” ResMusica, 16 April 2006

Turandot, Zürich, April 2006: “The irritation [with this staging] is lost in the fortissimo frenzy of conductor Alan Gilbert [and an orchstrestra whose] playing is often imprecise. Normal singers would have problems with this. José Cura (Calaf), however, is more suited to this kind of music-making, because when he is not above a mezzoforte, his tenor sounds brittle. But [Gilbert] allowed him to let go all out and as a result you experience a vocal power that is second to none. Cura's pride goes as far as arrogance, his strength as far as self-absorption. His posturing is perfectly suited to the type of Calaf he is supposed to play.” Aargauer Zeitung, 11 April 2006

Turandot, Zürich, April 2006: “José Cura in the role of Prince Calaf, on the other hand, impresses not only with his singing, but above all with his charming and self-confident demeanor. For fans of great Italian opera, this is an unreserved treat.” Arte-TV, April 2006 Turandot, Zürich, April 2006: “José Cura is irritating in his portrayal of unabashed Western arrogance, which he plays off coolly, uninhibited in his use of vocal power, in which he nonchalantly ignores bel canto ideals, even accepting a swollen mid-range and roaring high notes: a less than likeable hero in view of the bombastic finale - and a production that comes to terms with this finale so cheerfully and thus absolves the tenor daredevil. Still, a captivating evening in many respects.” Der Landbote, 11 April 2006

Turandot, Zürich, April 2006: “The first performance of this gigantic opera was a triumph for more than one reason. The first was the music. The second reason was named José Cura. His imposing presence made us think the opera should have been called Calaf, but much of his macho self-aindulgence can be easily forgiven thanks to the charisma that characterizes this artist and the almost insulting brilliance of his vocal projection.” Ópera Actual, 9 April 2006

Turandot, Zürich, April 2006: “A frequent visitor to the Zürich stage, José Cura made a strong impression as Calaf. In fine form, the Argentinian tenor sang with dark and vigorous tones and [easily] launched the high notes, even singing ‘Nessun dorma’ lying on his back! In contrast to other recent appearances here, he showed scrupulous attention to style and score. And he had no problem playing the macho lover required by the staging. It’s just a pity he often skips vowels.” ConcertoNet, April 2006

Turandot, Zürich, April 2006: “José Cura, as Calaf, focused entirely on tenor power, accepting the bel canto-like singing of the notes as well as the massive coloration of the vowels ("silanzio").” Tages-Anzeiger. 11 April 2006

Turandot, Zürich, April 2006: “There he is, the Calaf of José Cura, standing casually, with a cigarette stuck in the corner of his mouth, wearing a leather jacket and black jeans, puffing and listening to the warnings of the Chinese Emperor Altoum, surrounded by dozens of Chinese “choir zombies” who represent the “bad guys.” We are shortly before the three questions that Turandot asks her suitor, she and her entourage in traditional Chinese costume from “back in the day,” he in a western-modern dandy look. Here the bloodthirsty barbaric China of antiquity, there the enlightened neo-liberal economic miracle of the present. The macho role of Calaf is tailor-made for José Cura, who masters it with bravura. However, his voice, bursting with power, never abandons the powerhouse mode; lyrical nuances and beautiful phrasing are not the tenor's thing. He is powerfully supported by the opera house orchestra under the direction of Alan Gilbert [who unfortunately oversaw], thick music-making. St Galler Tagblatt, 11 April 2006

Turandot, Zürich, April 2006: “Everything, including the direction, was focused entirely on José Cura, the Argentinian star tenor with an enormous vocal volume. Cura was the only one on stage wearing modern clothing with a black leather jacket, T-shirt and black jeans. And he mainly played himself throughout the evening. The conductor gave him free rein. Cura's Calaf is a smug sexual-predator who coolly lights a cigarette during the imperial ceremony before the fateful riddles and impatiently waves his hand because the ceremony is taking too long for him. He solves the riddles just as coolly by consulting the Internet on his laptop, and he dismisses the ministers with macho gestures. He sings as one-dimensionally as he is portrayed in the play. Great, of course, full of power, but rather monochrome.” Zurcher Oberlander, 11 April 2006 ****** Turandot, Shanghai, February 2007: “[Cura] stretched on the ground to sing his famous aria ‘Nessun Dorma,’ perfectly striking high B. His melodious vocals with beautifully held top notes were expertly controlled.” Shanghai Daily, 10 February 2007

Turandot, Shanghai, February 2007: “José Cura's stage presence is outstanding, and he has masterful control over both performance and character development. Every detail was outstanding, including the ease with which he sang Nessun Dorma while lying on the ground, his emotional changes while guessing riddles, and his sadness when confronted with Liu's suicide.” Ximmin Evening News, 8 February 2007

Turandot, July 2007 /8, Zurich: “José Cura is often the subject of controversy: his style of singing has a way of both irritating purists and thrilling decibel-loving audiences. The singer's voice is indeed powerful, but his technique sometimes flies in the face of the rules of the art, with his high notes tacked on as if to elicit more applause from fans already won over... [that said] the Calaf of José Cura, whose timbre confirms his suitability for Puccini roles, is carefully considered and convincing. Cura, a singer naturally endowed with great stage charisma, is able to give his character creditable phrasing and studied sensitivity, blending everything with an awareness of stage and theater that makes his characters theatrically complete, dramatic and engaging.” Scene Magazine, 1 March 2008

Turandot, Zürich, December 07 / January 08: “The audience cheered frenetically at the premiere, and the evening was indeed of a high standard in terms of the singing and orchestral music. Tenor José Cura's nasal coloring was distracting but his athletic, muscular vocal power and his expansive range of emotions were highly impressive. And with a performance that ranged from powerfully combative to casually enacted, including a healthy dose of Latin lover eroticism, he was the ideal Calaf for this evening.” Sudkurier, February 2008

Turandot, Zürich, December 07 / January 08: “The Calaf of José Cura, whose timbre confirms his suitability for Puccini roles, is carefully considered and convincing. Cura, a singer naturally endowed with great stage charisma, is able to give his character creditable phrasing and studied sensitivity, blending everything with an awareness of stage and theater that makes his characters theatrically complete, dramatic and engaging.” L'Opera, February 2008

Turandot, Zurich, July 2008: "Giancarlo del Monaco's dark, visually stunning encounter between a modern young man (Calaf) and a frigid and instinctively repressed young woman trapped in her tradition (Turandot) has lost none of its fascination since its premiere. José Cura played Calaf with a twinkle in his eye, flirting not only with Turandot but also with the audience. His voice was perfect that evening, allowing him to begin the hit Nessun dorma lying on his back without losing any of his melodiousness." Oper-Aktuell, 12 July 2008

Turandot, Zurich, July 2008: “Imagine a modern-day European proletarian from the suburbs, a burly dark-haired guy in a leather jacket, almost bursting out of his skin with self-confident masculinity. This is Prince Calaf. And also José Cura. And that's how he sings. Dominant, loud and impressive. Whether he is stubbing out his cigarette out on the palace floor, which he is trying to put out - because he is bored – as the wise men of Emperor Altoum (Miroslav Christoff) are trying to dissuade him from getting involved in the deadly riddle game of the ice-cold princess (Paoletta Marrocu) or is consulting his laptop during the actual riddle game, whether he is holding the defeated Turandot in the final act as God the Father on a throne, he is and remains the guy from the West who rescues China from its paralysis and obsolescence. The fact that the man-woman relationship resembles that of The Taming of the Shrew further complicates the whole thing. José Cura, who has been criticized for his interpretation of Calaf, plays and sings this interpretation brilliantly. And if we didn't suspect that he was portraying himself in terms of acting and singing, our admiration would be even greater.” Welt Express, 15 July 2008

Turandot, July 2008, Zurich: “José Cura's stage charisma more than once borders on the macho persona, so much so that the first source of his appeal is the very quality of his voice, with incredibly deep baritone colors. The voice comes through very well and the singing isn't messy like the Samson with Denyce Graves broadcast by the Met on radio, where he did a bit of everything. However, there emerges a certain impression of casualness. We may appreciate that Cura sings piano on more than one occasion but, on the one hand, this piano seems rather crooned here and there and on the other hand seems a way of glossing over the details of the score, even to the point of avoiding them. That noted, Cura is very pleasant listen to and, on balance, his singing is more captivating than the performance that I found to be of minimal engagement.” Le Blog, 18 July 2008

Turandot, Zürich, April 2006: “José Cura was announced as indisposed; coughs and beads of sweat plagued the singer. Nevertheless he was able to inspire and survived to the end in good shape. His ‘Nessun dorma’ was brave and his interpretation was convincing and often amusing. He solved the riddle with a laptop and gave us the best of an earthy and macho but gentle Calaf.” Der Neue Merker, May 2009

|

|

|

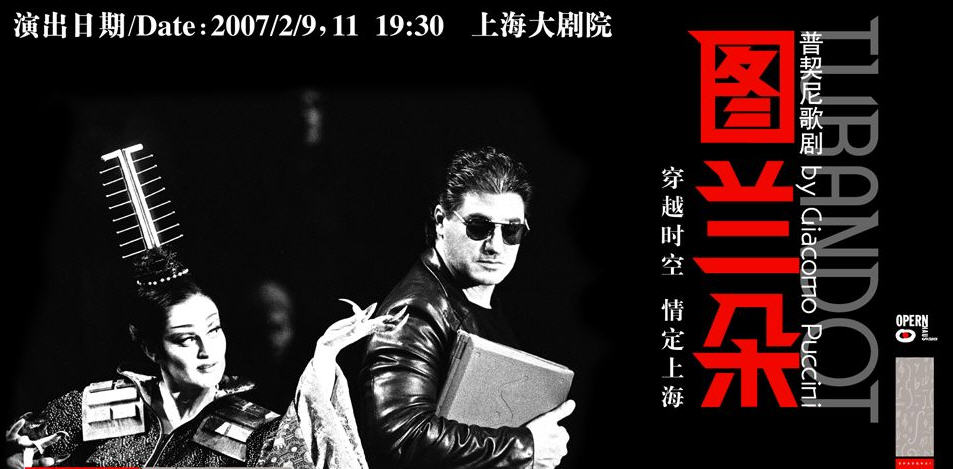

Shanghai 2007

|

New version of "Turandot" debuts at Shanghai Grand Theater Wenhui Po Xing Xiaofang 06 February 2007

[Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpt]

This Friday, a new version of the opera Turandot will be unveiled at the Shanghai Grand Theater. All seats have been sold. Yesterday morning, conductor Lu Jia, together with José Cura (Prince Calaf), Paoletta Marrocu (Princess Turandot), and Yao Hong (Liu), appeared at the Shanghai University Theater. "Modern + Shanghai" are the two major elements of the new version of Turandot. This opera, first performed in Europe last year, is a joint production by the Shanghai Grand Theater Art Center, the Shanghai Opera House, and the Zurich Opera House in Switzerland. It retains the classic and beautiful music of Puccini's original work but makes creative changes to the plot, costumes, and scenery, including moving the ending of the story to Shanghai. The Tenor José Cura, who plays Prince Calaf, is a big tenor (career-wise and physically). At yesterday's meeting, Jose, wearing a pink sweater, shared his sense of humor with the reporters. He said, "Turandot is not a love story. I think this prince's romantic surface conceals his desire for power and status. The princess falls in love with him, but what the prince loves more is the king's throne and status. I think this prince is quite an 'idiot' but I hope you do not think I am that kind of 'idiot'." One of the first innovations in the new version of Turandot is to introduce digital technology into the play. Calaf drops into ancient times with a laptop and uses the computer to easily answer many questions that so many other hadn’t been able to and who lost their lives as a result. Cura said, "The modern elements in this version of Turandot are actually great, because the story itself has no specific place in time. Do you think I want to play a Chinese well just because I came to China for the first time? No, no, I don't have such arrogant fantasies; I just want to play a role in this legendary story." His sense of humor once again won laughter and applause. Zurich and Shanghai "handshake" The most daring scene in this new version of Turandot occurs at the end of the opera. All the actors take off their ancient costumes and became modern, singing and dancing against the backdrop of the Oriental Pearl Tower on the Bund in Shanghai. In this regard, the director of the play believes, "Turandot writes about ancient China in the eyes of Westerners. What we want to show this time is today's China. This version is the Zurich Opera House's tribute to China and Shanghai. This version being presented in its Asian premiere in Shanghai means a successful 'handshake' between these two important cities."

|

|

That's some tenor! Shanghai Daily Michelle Qiao 02 February 2007 [Original article was published n English] Argentine tenor José Cura sings a superb Prince Calaf in Turandot and immodestly says his "good shape, big and strong" is ideal for the role. But he calls the greedy, kingdom-hunting character "disgusting" and hopes Chinese audiences won't think ill of him, writes Michelle Qiao. Opera singers often identify with, even love their roles, but Argentine tenor José Cura loathes "Prince Calaf," his character in the opera Turandot staging this weekend at the Shanghai Grand Theater. "Turandot is not a love tale, but a tale of interests and greedy people trying to seize power," he said during a press conference this week. "The character of Calaf is not romantic. Chinese Princess Turandot loves Calaf but Calaf wants her for her kingdom, money and power. He is superficially charming but behind the mask he's an idiot, disgusting. "The Prince has lost his own kingdom and searched in the world for another kingdom," says Cura. "He put in danger the people he loves to obtain something he wants." "I'm sorry that for the first time in China, I must play an idiot. Please don't think ill of me or link me with the character." However, playing the black-hearted and designing prince, the tenor still impressed his Shanghai audience with his charming "surface" and superb voice last night. This production of Turandot is a treat for the eyes because both Cura and soprano Paoletta Marrocu, who sings Turandot, are in good shape compared with other overweight Calafs and Turandots in the opera world. "My good shape, big and strong, is the result of many years of physical training in my early days," says Cura, wearing a pink sweater and a pair of comfortable white sneakers. "In the past, a long time ago, I weighed 20 kilos less. Now I'm 44, 20 kilos more, and 20 years older." But he can still pass for a prince. "For roles in modern theater, if you look like the character it's better for the theater fantasy. Old audiences gave the greatest importance to good singing. But the younger generation likes good spectacles." Cura's charisma shone from the start of the production created by the Shanghai Grand Theater and the Zurich Opera House, when he showed up like a sexy secret agent in a black leather jacket, a tight-fitting gray vest and shades. In sharp contrast to the antique green copper hues of the set and the icy demeanor of Princess Turandot, Prince Calaf casually smoked a cigarette and searched his laptop for answers to Turandot' love-or-death riddles. He even stretched on the ground to sing his famous aria "Nessun Dorma," perfectly striking high B. His melodious vocals with beautifully held top notes were expertly controlled. With the Bund as the backdrop, the prince ended his dangerous love pursuit with a romantic candle-lit dinner with the cruel princess who had actually fallen in love and changed her weighty formal robes for a fitted scarlet evening gown. "Cura was not only acting, but also creating," says Zhang Guoyong, head of the Shanghai Opera House. "He demonstrated the talent of a true master." Unlike other opera stars who often give pleasant, bland comments during interviews, Cura was bold and forthright. "Mama Mia," he occasionally exclaimed when occasionally targeted with surprising questions. "I didn't know I'm famous in China," he said. "I thought I was completely unknown and so I could relax on stage. Now you will expect so much from me and I must rise to the challenge." No matter whether he likes it or not, Cura is widely known in China as "the world's fourth tenor" (after Luciano Pavarotti, Placido Domingo and Jose Carreras). "You can say I'm the successor of the three tenors who are as old as my father and you are also the successor of your own parents, right?" he says. "We are the next generation and the world was so different from their time around 30 years ago when CDs and DVDs had just been invented. "Now we face a big crisis of new media and the Internet and MP3s will be the future. If Bach were alive today, he might use a computer to write music. It's very complicated, not simply being a successor. It's difficult to succeed in the opera world today." Cura has been a rare artist who's not only a tenor, but also a conductor and composer. In addition to the two Turandot operas, he will conduct the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra for a concert at the Shanghai Grand Theater on February 14. "I will also try the role as an opera director," says Cura. "In every role I have put all my love, so I cannot say which role I'm best at. But what makes me happiest is conducting. I meant to do some deep, profound music for the Shanghai audience. But the organizers asked me to do some romantic music for Valentine's Day, such as Romeo and Juliet." As a tenor of IT times, Cura has an iPod with him that is filled with jazz, symphonic music, and his favorite singer Karen Carpenter - but no operas. "I don't like some untuned pop music," says the tenor. "I cannot have music as a background. If music is there, I will have to pay attention to it. So I only like music with dramatic objectives." Despite its modern elements, this production of Turandot closely follows the original Puccini plot. Princess of China, the dangerously beautiful Turandot, refuses to marry anyone but the man who can answer her three riddles. All suitors who fail will be put to death. Enchanted by her beauty - and kingdom - the unknown Prince Calaf dares to try and at last succeeds, at the cost of the life of his slave girl Liu, who is in love with him. "Prince Calaf has a disgusting personality," repeats Cura. "He can be a citizen of any country of any race, like the greedy people of all times. They don't hesitate to kill their mother to succeed." Well, maybe Cura feels it's a pity to show up as a man with disgusting personality for his China debut. But through his on-stage acting and off-stage talking, the tenor has showed Shanghai the unique personality behind "the fourth tenor." |

|

|

Zürich -- 2007 thru 2012

|

24 May 24 2009 was a day of superlatives at the Zurich Opera House Der Neue Merker May 2009 Marcel Paolino

[Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpt] It's hard to believe, but the Zurich Opera House manages to put on three top-class performances in a row on one Sunday and impressed with an internationally renowned line-up of singers that is second to none. The audience was enthusiastic from the first to the last minute. At eleven in the morning, Jonas Kaufmann gave a song matinee with Schubert and Strauss songs and in the early afternoon the opera Rigoletto. And last but not least, the extremely elaborate Turandot is performed late in the evening, with José Cura as Calaf, Paoletta Marrocu as Turandot and Elena Mosuc as Liù. It's hard to believe how the Zurich Opera House manages to bring so many performances and stars to the stage in a single day. The enormous work that the highly stressed stage technicians, choir and orchestra had to do should not be neglected. Which other opera house brings such diversity and a more illustrious cast in such a short space of time in a small space, and who can afford it? While people were walking into the Rigoletto performance in droves, Jonas Kaufmann was still busy in the foyer giving interviews and completing his book signing. As soon as the last curtain of the Rigoletto fell, the technicians were already rebuilding the stage for the next elaborate program. It's impressive how everything went smoothly and with practically no delay. […] José Cura was announced as indisposed and people visibly felt sorry for his cold, which could neither be ignored nor overlooked. The singer was plagued by coughs and beads of sweat. Nevertheless, he was able to inspire and get through the role well until the end. His Nessun dorma was brilliant and especially his convincing and often funny interpretation of roles. He solved the puzzles with a laptop and portrayed a macho, robust yet gentle Calaf. Paoletta Maroccu's acting is at a high level. Her facial expressions and behavior reflected the full spectrum of a woman who seemed frigid and arrogant, but also capable of learning and interested. In terms of vocals, however, compromises had to be accepted. The singer has a metallic, sharp treble, but her voice does not develop optimally. The higher they pushed the dramatic outbursts, the more vibrato the sound became and hit the ear in an unpleasantly direct way. Hello Elena Mosuc! Despite the long wait and the rather small role of Liù, she was able to come up with wonderful pianos again. Dan Ettinger, the conductor with his striking straw-blonde hair, led the Zurich Opera House orchestra with quite spirited and confident balance and was able to bring out the colors of the score to their full potential. The audience celebrated all performances with storms of enthusiasm and thanked the opera house for what was probably the most exciting program of the day.

|

|

|