Sights without sounds. The curtain rises as the secrets of

night prepare to give way to truths of day. These minutes

before the music begin offer director Cura a chance to

effortlessly establish the enjoined nature of both stories and

give hints of the double tragedies ahead: in silence the opera

in front of us is neither Cav nor Pag

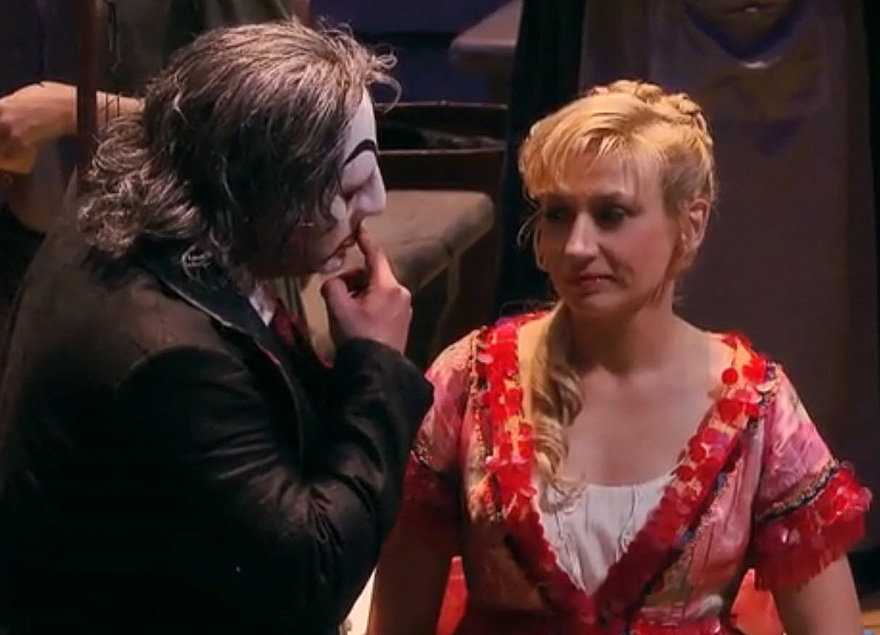

but a promise of an extraordinary rethinking of both. Lola and

Turiddu, laughing and loving on the balcony above Mamma’s

cantina, look on approvingly as shy, uncertain Silvio and

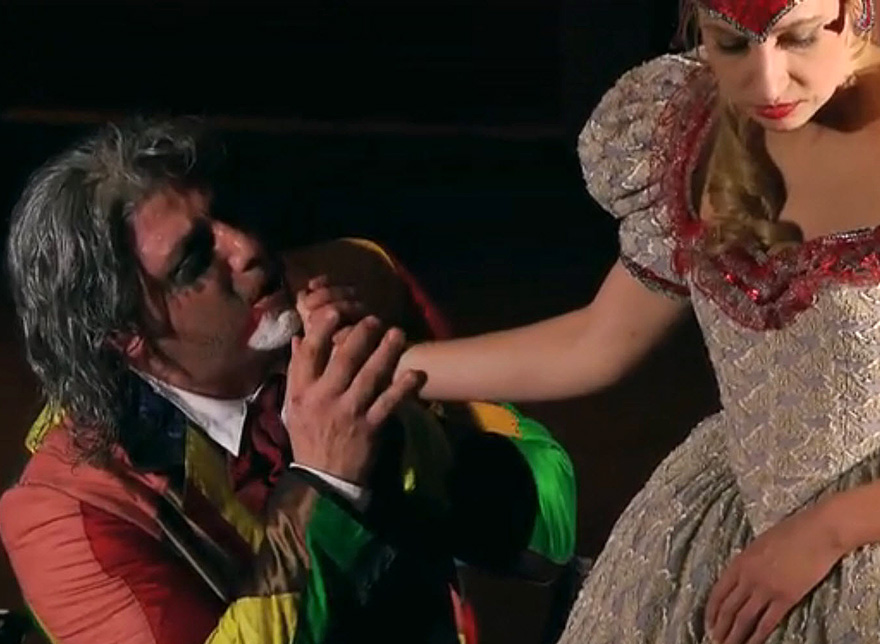

unhappy, needy Nedda begin their romance. In due time Turiddu

leaves the balcony, reappearing below to catch the hat Lola

tosses to him; he hands Silvio the keys to the cantina before

disappearing into the background, a prophetic passing of

responsibilities and a locking together the fate of both men.

But Cura is not yet finished setting the stage. The

street-sweeper cleans the remnants of the past, the priest

emerges to nurture the town drunk, a couple appear to bicker in

a window—the stories of Santuzza and Turiddu and Silvio and

Nedda are just two of many threads in the tapestry of this town

and Cura is making an early and emphatic statement that his

staging is as much about community as it is about individuals.

The music swells as Pietro Mascagni arrives to observe, the

artist watching his story play out, powerless to stop it; the

composer will remain on set for the length of the opera.

The Siciliana is treated as more than a pastoral love song: it

is used to illuminate Lola’s dark nature. As Turiddu’s voice

rises, Lola moves to the window overlooking the town square,

reveling in her power over him. When Santuzza appears a few

windows down, pulled by the sound of the man she loves, Lola

delights in Santuzza’s frustration and pain; her hold on Turiddu

seems as much about ownership and sense of entitlement as it is

about love.

Cura takes the time to introduce the village during

Gli aranci olezzano sui verdi margini.

Silvio is the conscientious, obedient son to Mamma Lucia that

Turiddu can never be; the village people, preparing for the

Easter ceremony to come, are good-natured neighbors who give

coins to the town drunk and help reunite the quarreling

couple. And Mamma Lucia doesn’t pull away from Santuzza when the

young woman tries to tell her she has slept with Turiddu--her

heart is too big for that. Instead, their conversation is

interrupted by the arrival of Alfo and it is only with the

introduction of the teamster that a truly negative texture is

added to the otherwise happy town. As he boasts about his work

(Il cavallo scalpita), Lola is on her balcony blowing

kisses and making suggestive movements toward her husband--she

enjoys her dangerous game as much as her husband enjoys his

position in town.

The Easter hymn is simply and beautifully staged, with the

procession coming from the church to set the holy image inside a

niche in the wall—the love of God isn’t confined to the space

within a building even if the conventions of the Church work to

keep some outside. And when the crowd leaves Santuzza to enter

that structure, the town drunk, also unable to enter the church,

attempts to reach out to the living spirit he finds within the

woman.

Turiddu and Santuzza are not alone during their initial

confrontation: Lola watches from her apartment, increasingly

concerned that Santuzza’s pleas might move the honorable

Turiddu. She hurries downstairs to remind Turiddu of what he

risks losing and after having re-establishing ownership, she

heads into church—though not before pulling a number of bills

from her purse, waving them in the air and then throwing them

into the outstretched hat of the drunk that until then had

captured only coins. Lola isn’t about to let anyone forget her

wealth, her status, and her entitlement.

Once Turiddu follows Lola into the church, Santuzza is once more

supported by the drunk, who offers the one thing he holds

valuable, his wine bottle. This time she takes it and drinks

long. When Alfio returns and with her self control momentarily

lost, she tells him his wife has been unfaithful. Alfio's rage

scares her but she tries to calm him. Unable to undo what she

has done, Santuzza runs off.

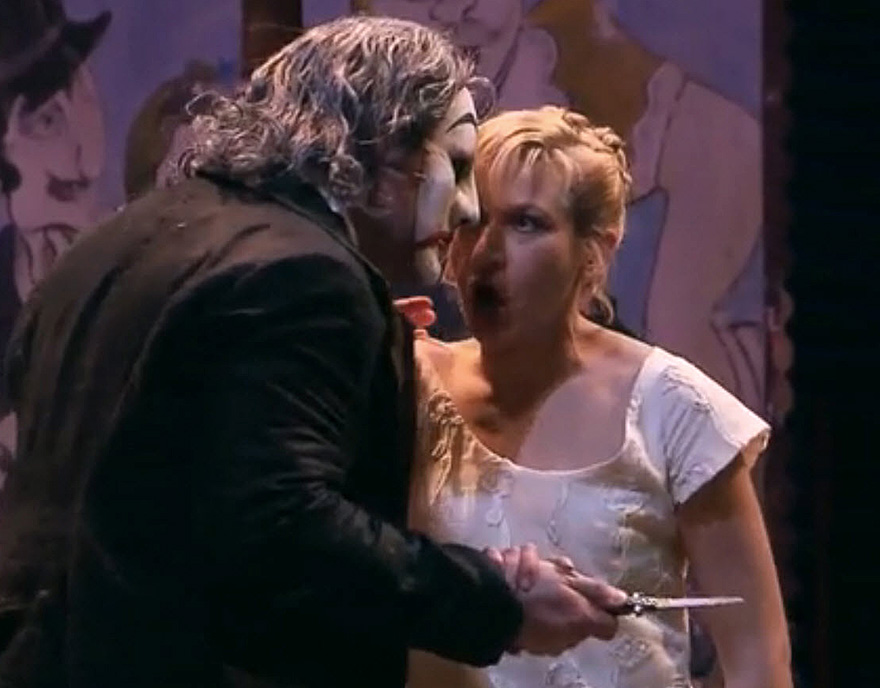

The Intermezzo takes on additional impact when

Cura stages a reenactment of the opening scene, with ‘Turiddu’

coming once more from ‘Lola’s’ apartment, but this time the

action in mimed through dance, a tango choreographed to Cura’s

design. Beautiful in its sensual lines, touching in its simple

emotion, deadly in ‘Lola’s’ final, fatal thrust, the Intermezzo

compresses the opera into a few haunting moments of revelation.

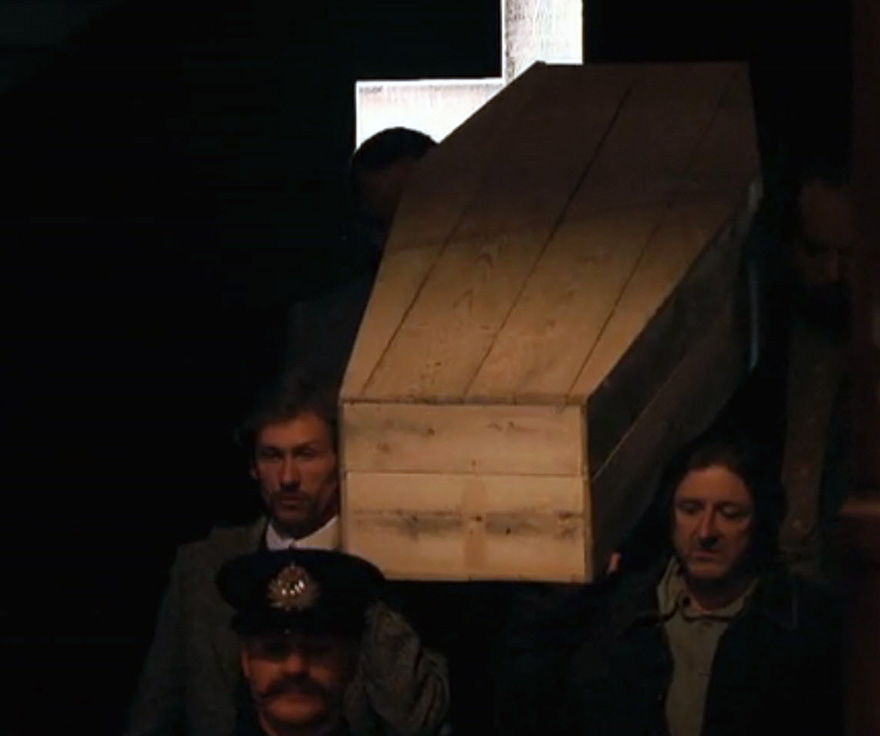

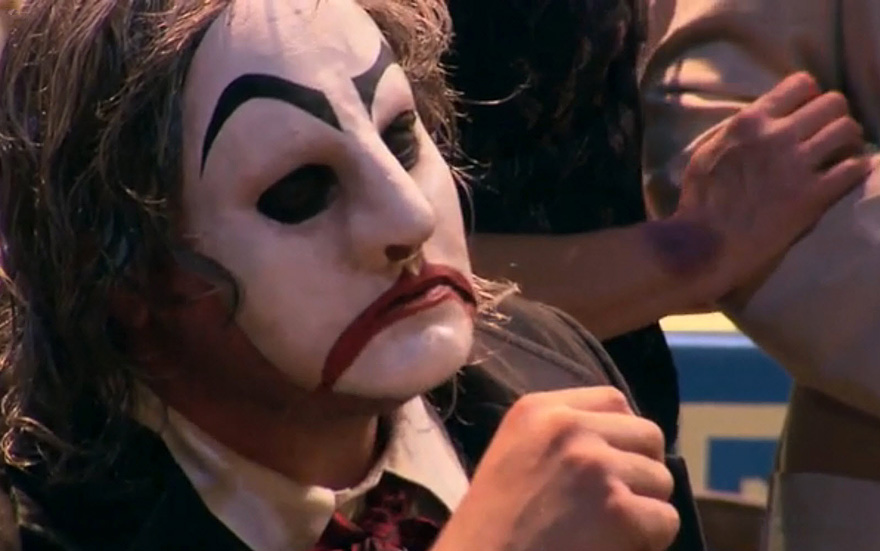

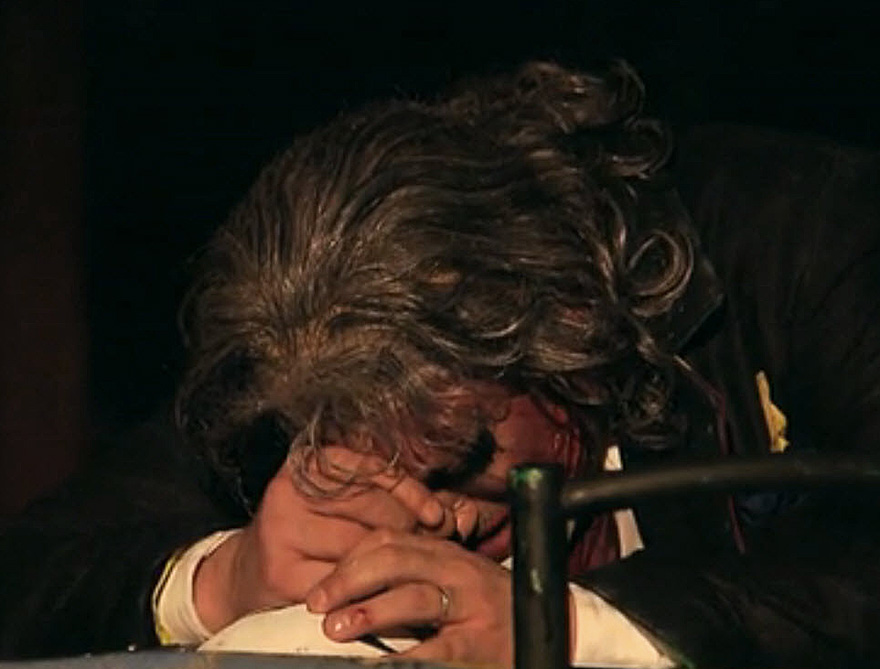

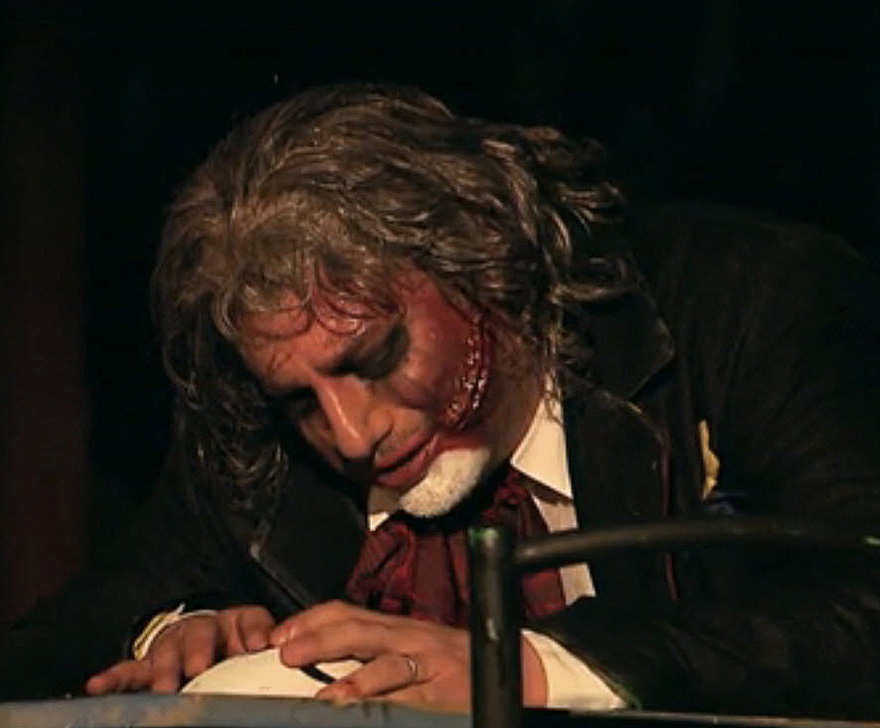

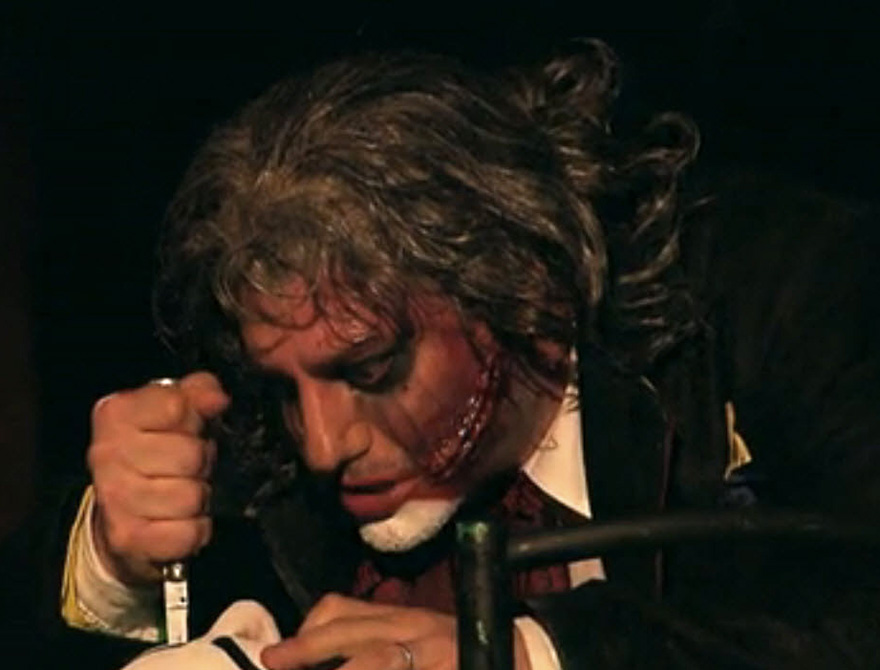

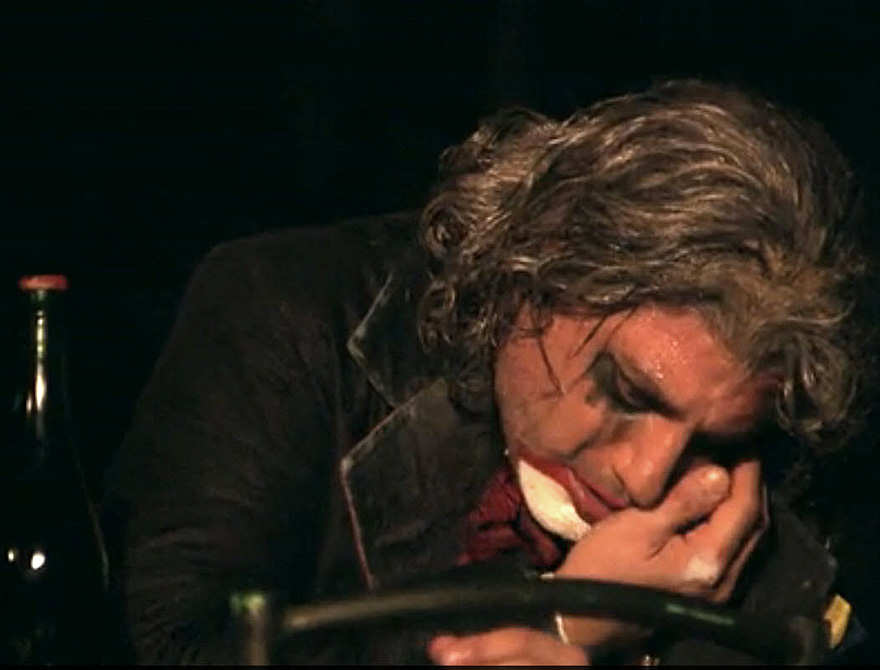

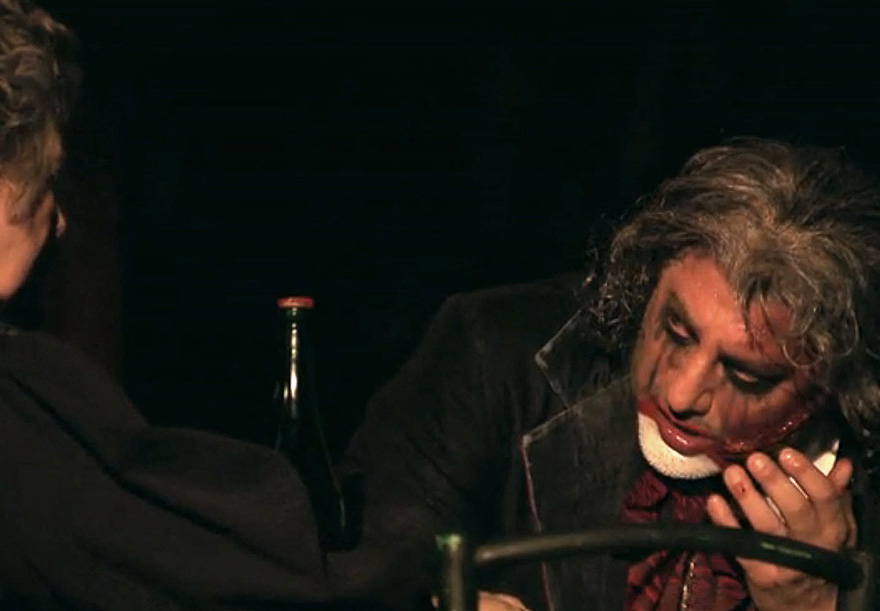

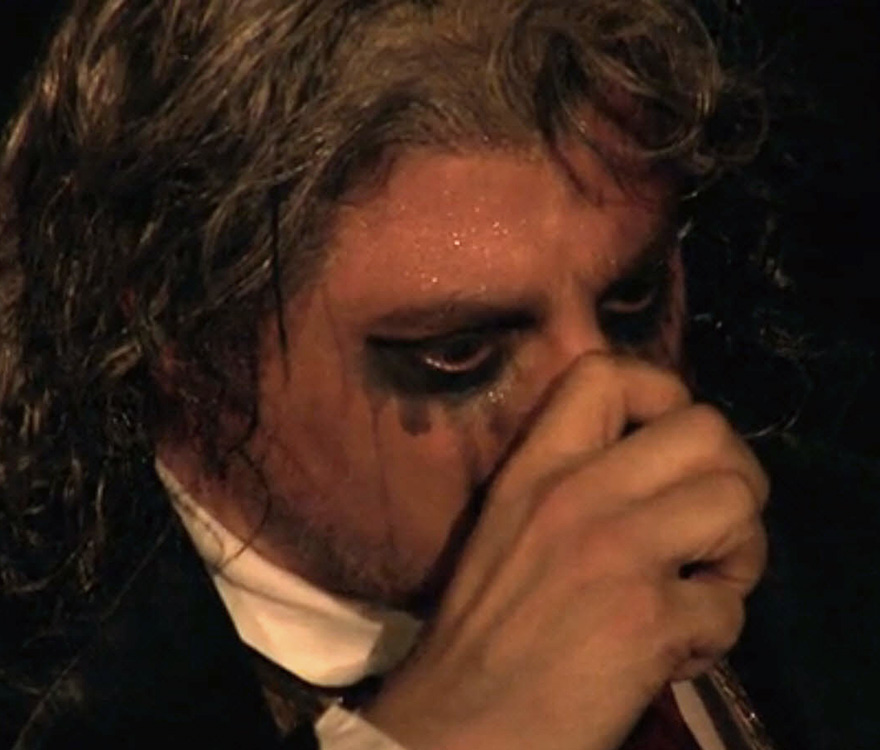

The denouncement comes quickly: Alfio and Turiddu confront each

other, Turiddu bids a tearful farewell to his mother, relying on

her good heart to embrace Santuzza as the daughter she would

have had were he a better son, and runs off to be killed. The

community comes together in their grief. Mascagni mourns.

And yet….the opera doesn’t end, any more than the town

disappears or the people cease to exist. For Cura, life

continues without break and the death of Turiddu was just one

tragic event in a cycle. Life goes on. And so as the stage

lights dim and night comes upon the town, a

bandoneón player takes his place on stage to connect the two

operas, to reinforce the continuity of all things.

Take-away:

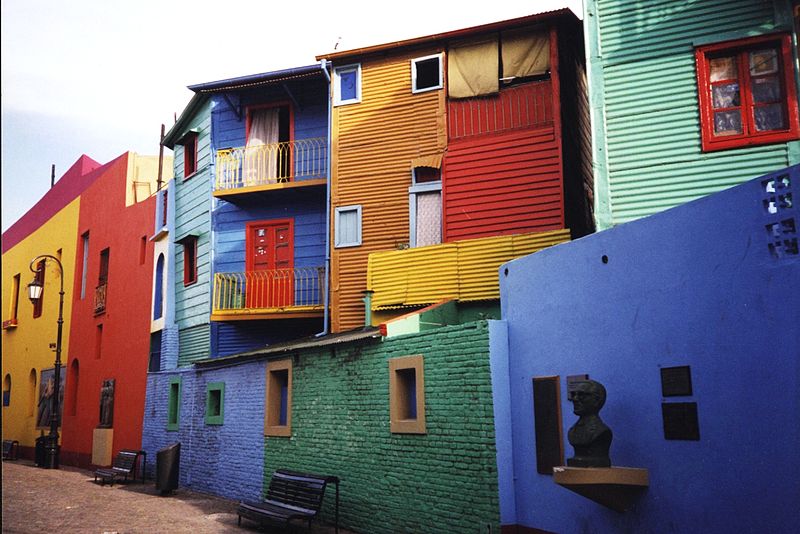

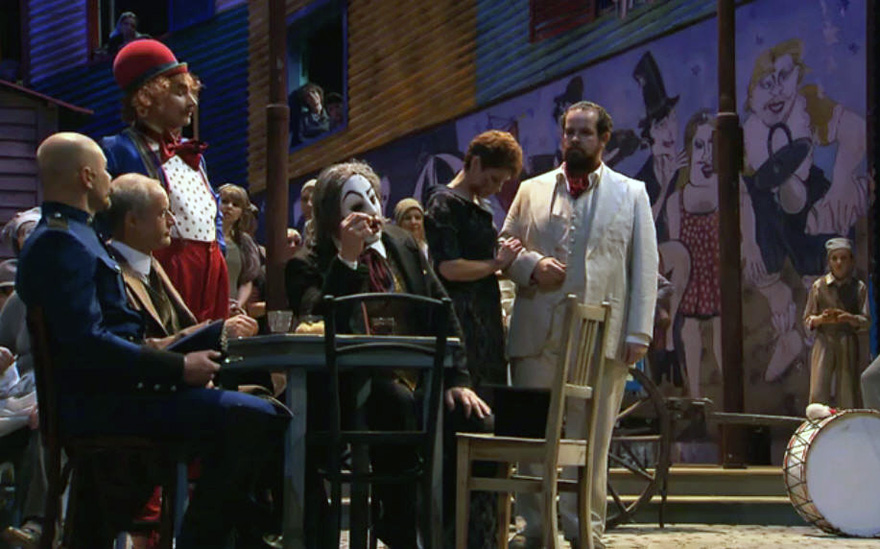

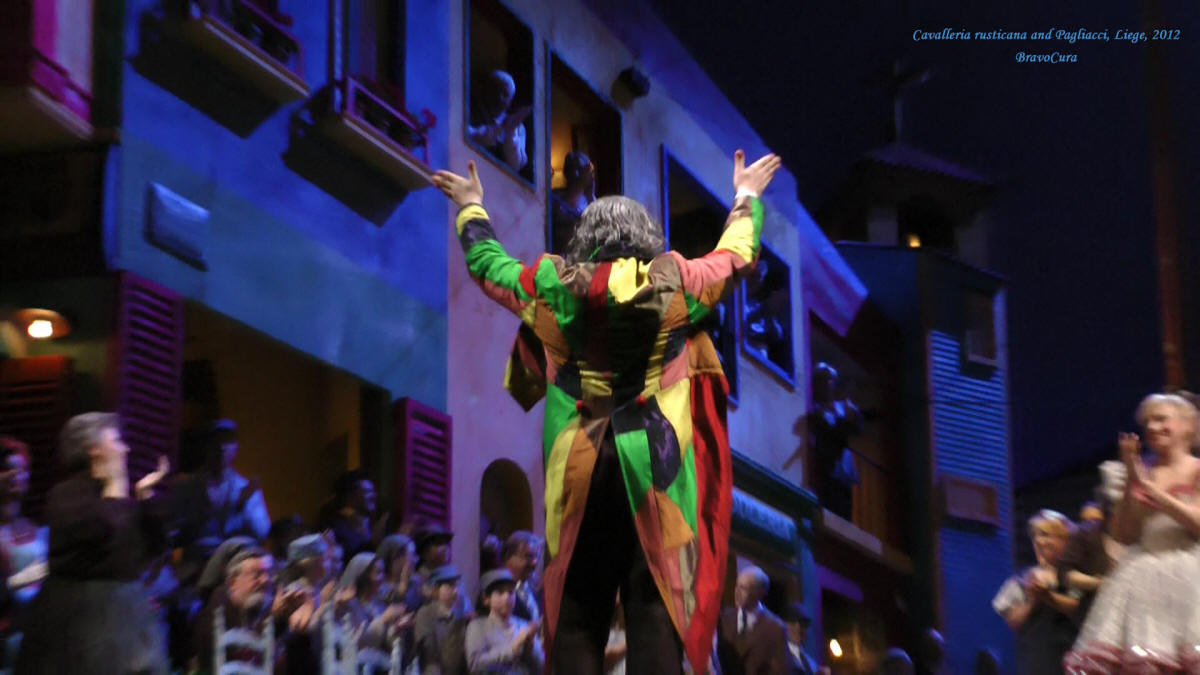

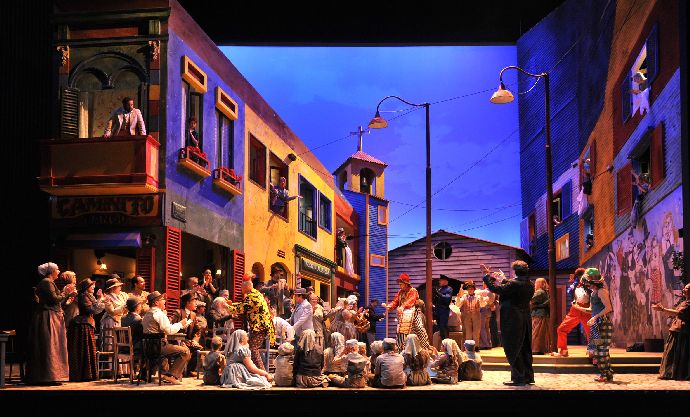

The set design was a brilliant fusion of old and new world that

allowed Cura to mix elements from both to create a wonderful

dynamic. He invested time and effort with the chorus and the

supernumeraries to create a living, breathing environment in

which to insert his stories. He brilliantly choreographed the

action, bringing the drama front and center but never forgetting

to fill the interstices with the real sense of life—there was

never a moment without activity, without purpose. It was a

breathtaking suspension that was so compelling the audience was

loathed to leave the auditorium during the intermission (during

which the bandoneón player continued to play).

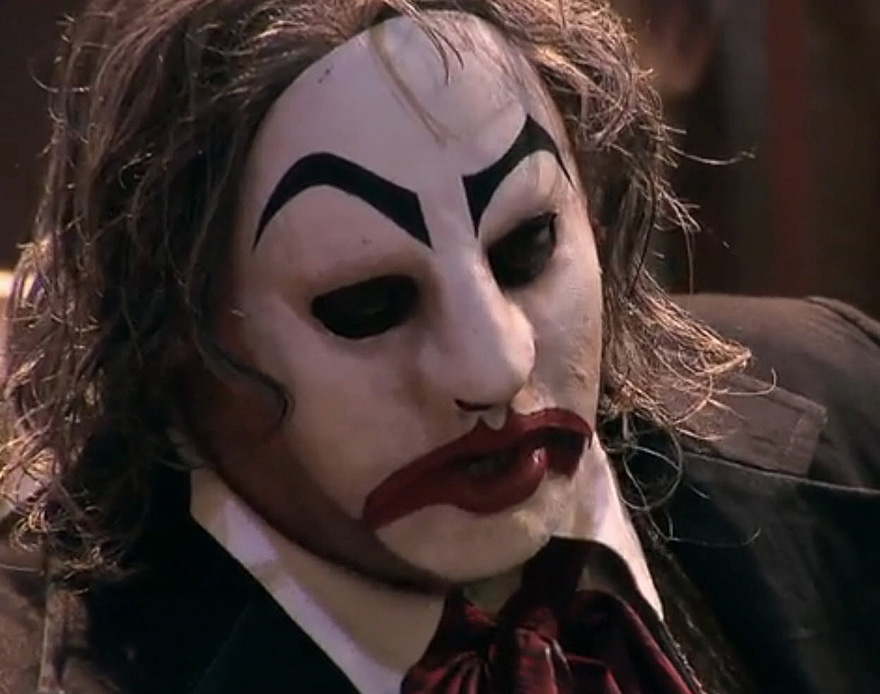

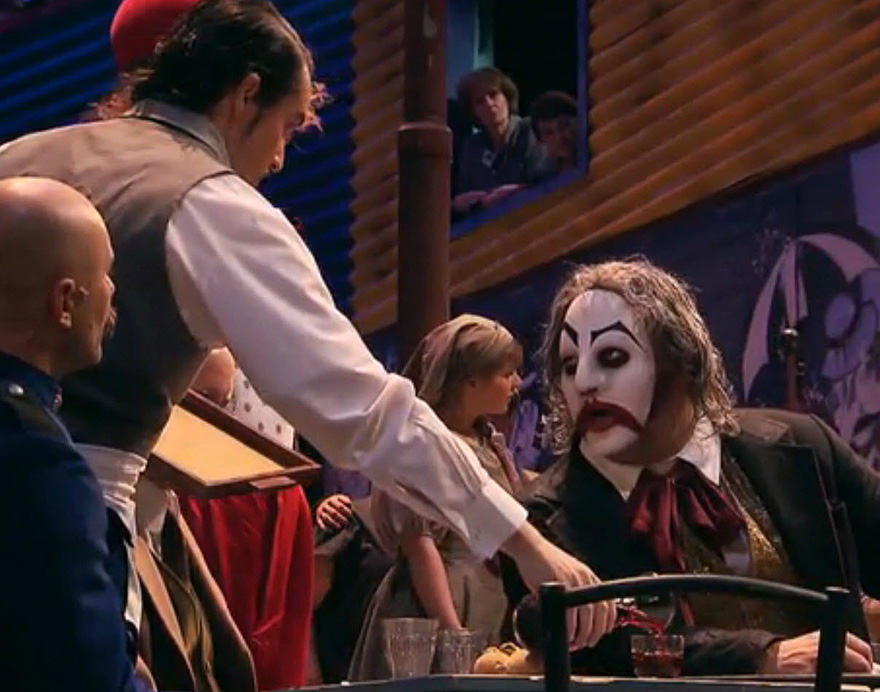

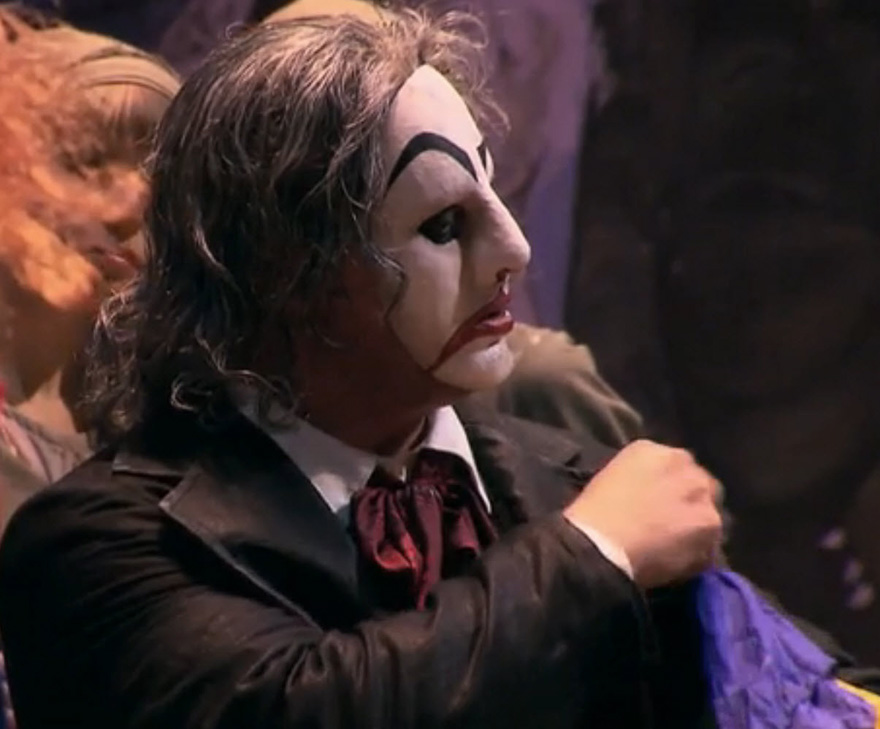

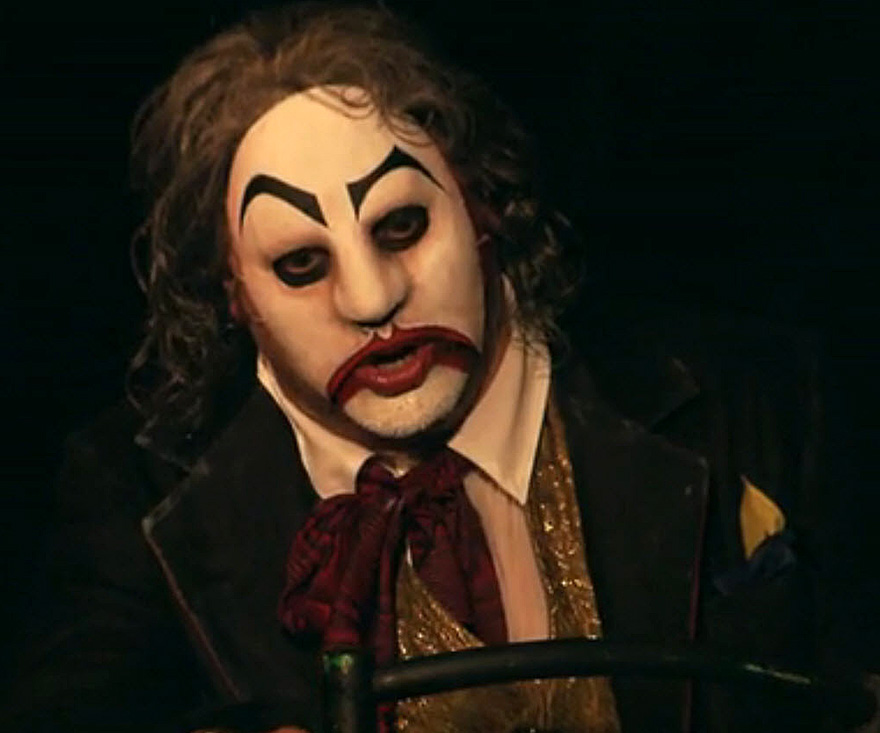

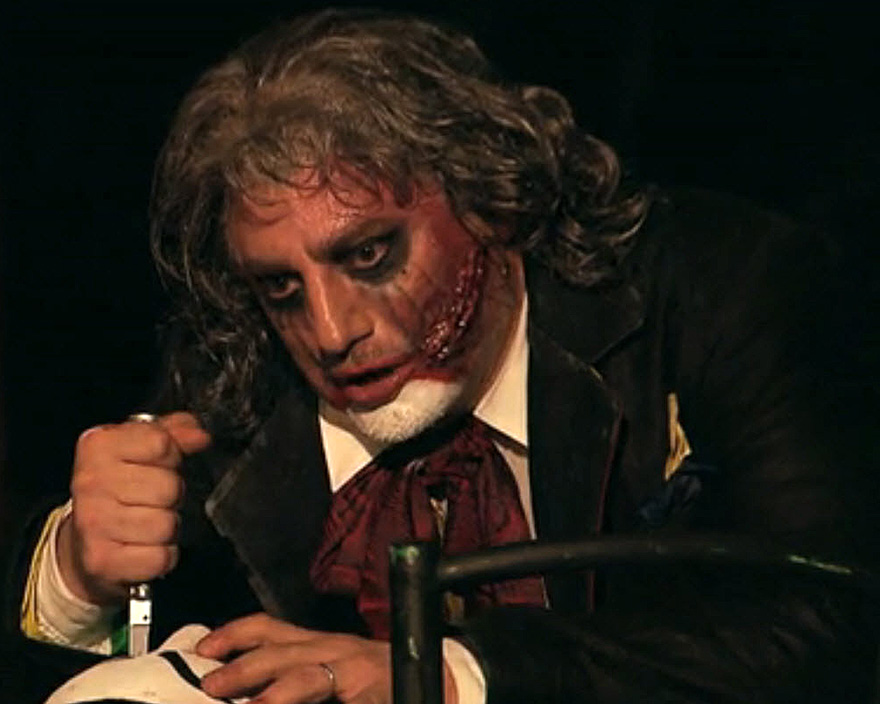

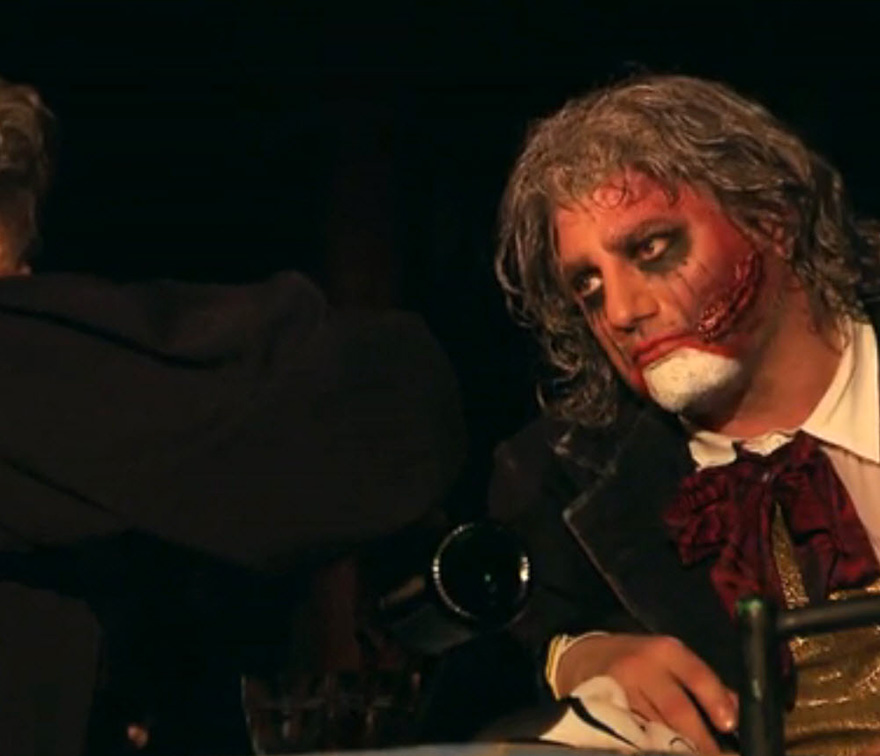

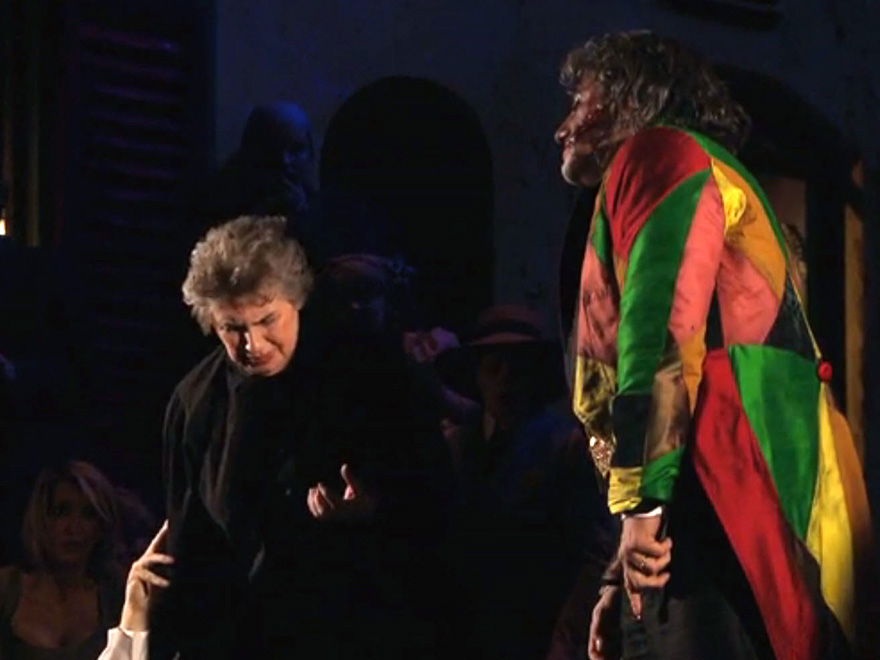

The addition of Mascagni to oversee the opera seemed at first a

risk but was ultimate a successful conceit: the composer was

every one of us in the audience, aware of the trajectory of the

story but unable to stop the inevitable. He channeled our

emotions in silence, his expression mirroring our feelings.

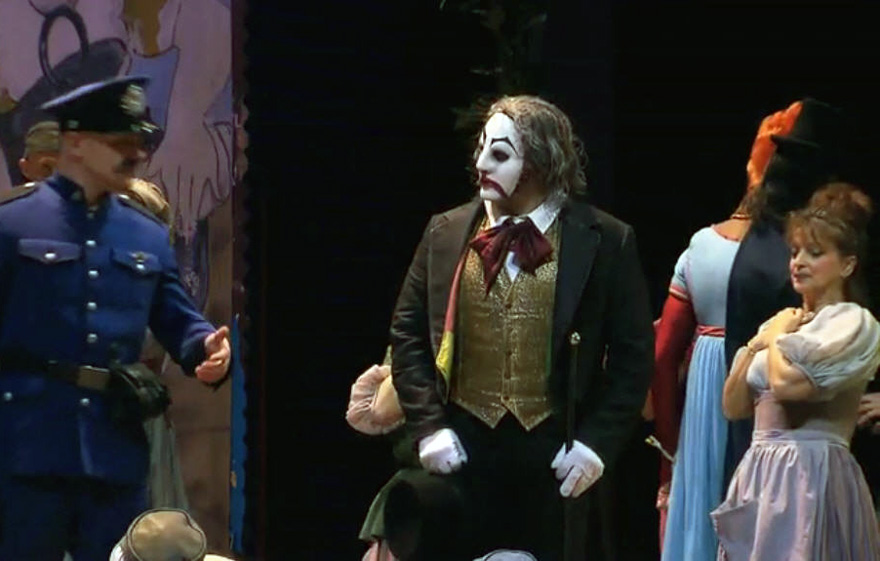

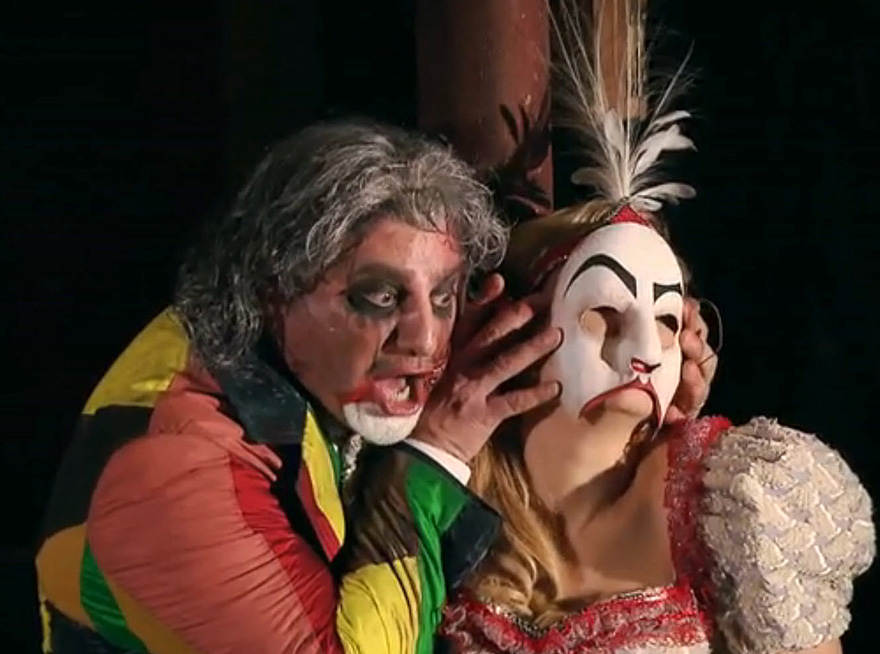

The early introduction of Silvio (and Nedda) gave the character

a much needed history, adding an overall pathos to Pag. His

quiet, conservative, dedicated approach to work, his attention

and devotion to Mamma Lucia before Turiddu’s death and

afterwards, make us care for this young man and ultimately adds

even greater pain to the ending.

The actor who played the drunk deserves special mention (as does

Cura for including him); the outcast accepted by the townspeople

in turn became the protector of the outcast who has not yet been

embraced. This unexpected performance added a layer of

continuity and compassion to an opera that can sometimes suffer

from flatness.

The tango ballet: bravo! What a brilliant, original use of

time and space in the opera! If only other directors would be

as inventive and allow them to think outside the proverbial box!

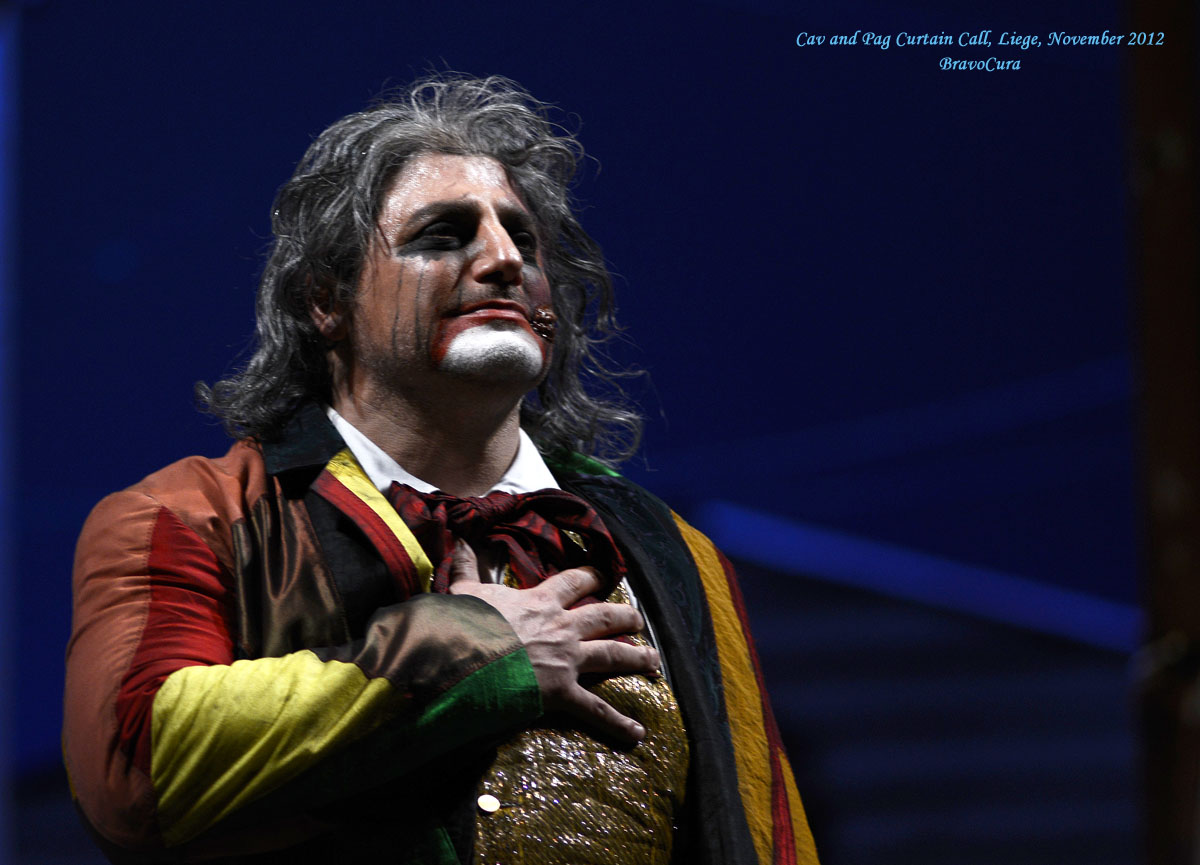

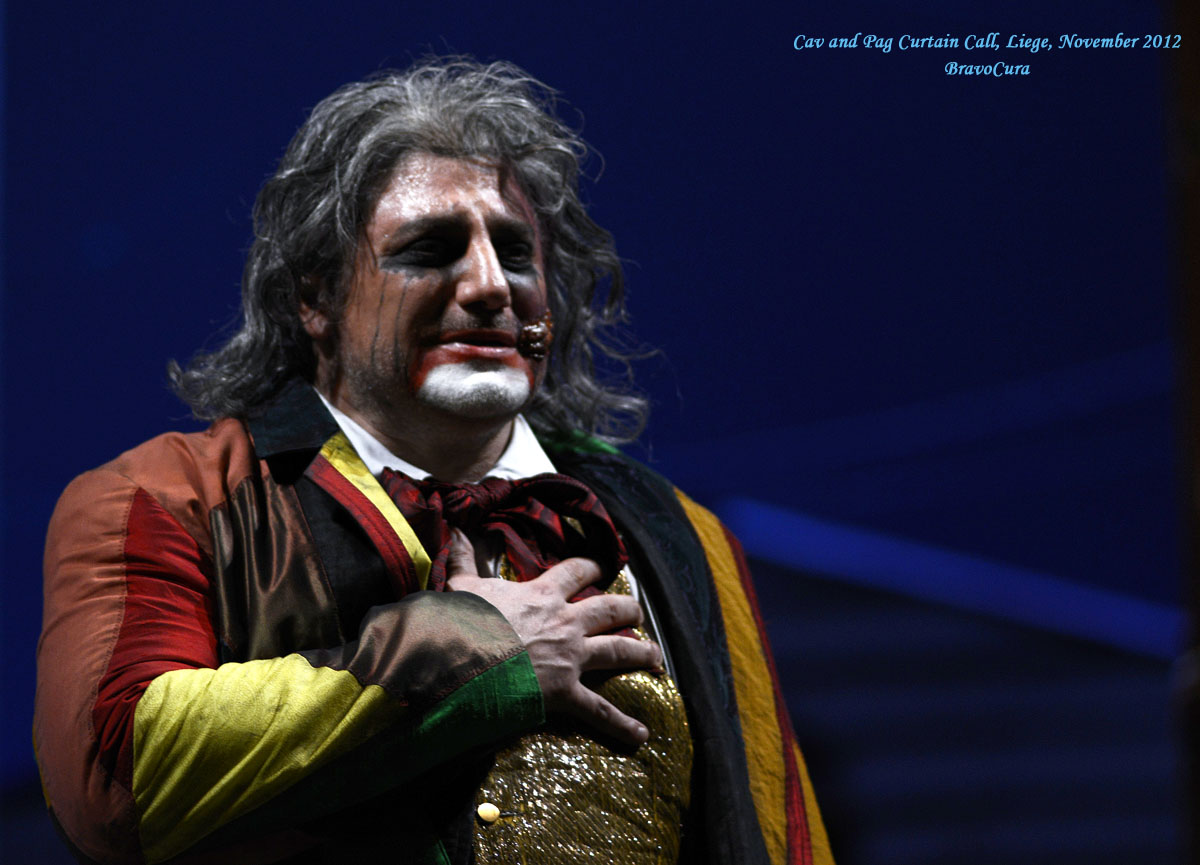

The performance from the principles: In spite of persistent

illness among the cast, the intensity of the leads, the

attention to detail, and the delivery of the music remained at

the highest quality.

Director Cura: his care and concern and compassion and

understanding of this work were evidence from the opening

moments. His attention to detail was outstanding. His

placement of character, his balance between action and inaction,

his inclusion of nuance that added the necessary depth this

opera needed was remarkable. His innovation was never

introduced without purpose. This staging is one that should

travel, and there are a lot of well-established, highly

successful directors who could learn much in examining the work

Cura has done in Liege. I’m already looking forward to the

next….

.jpg)

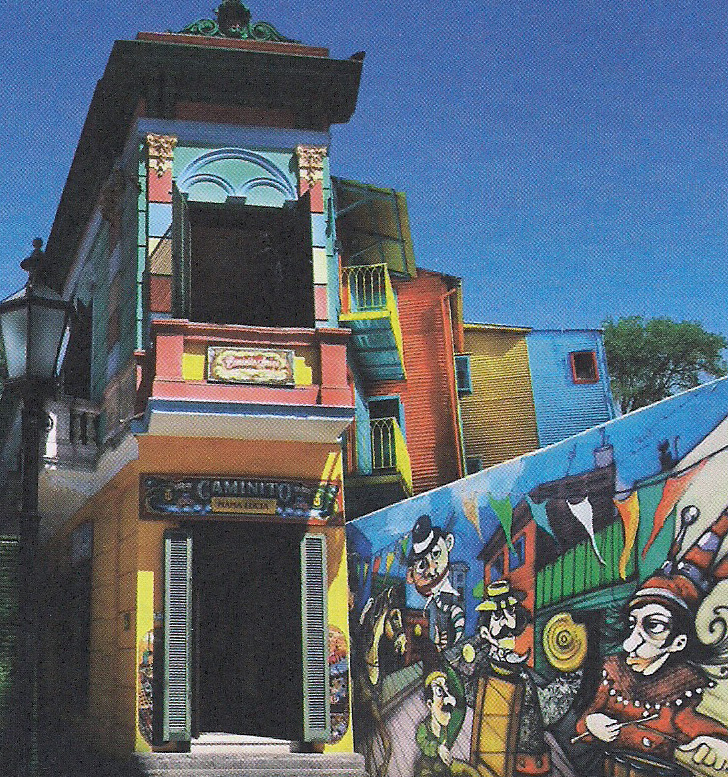

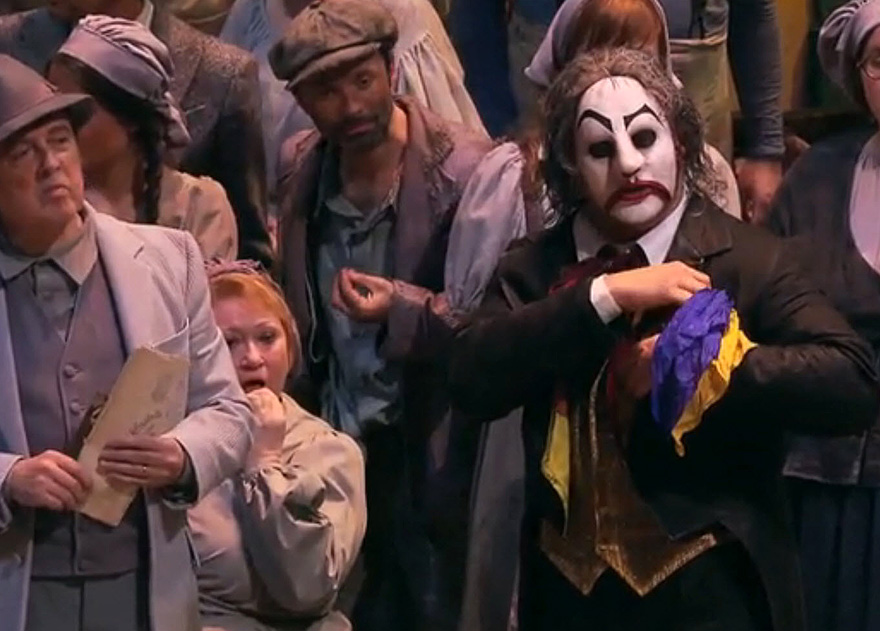

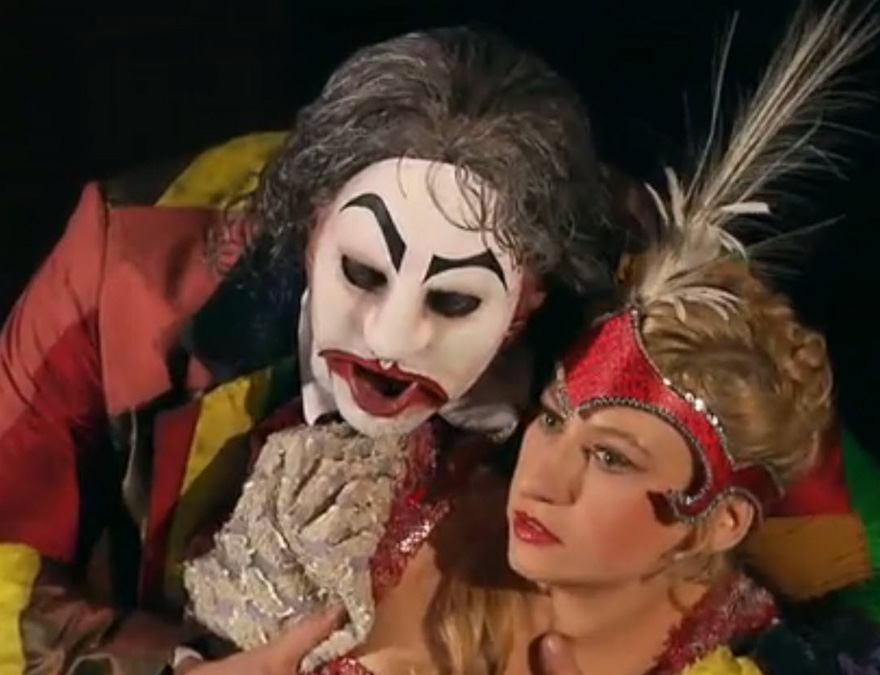

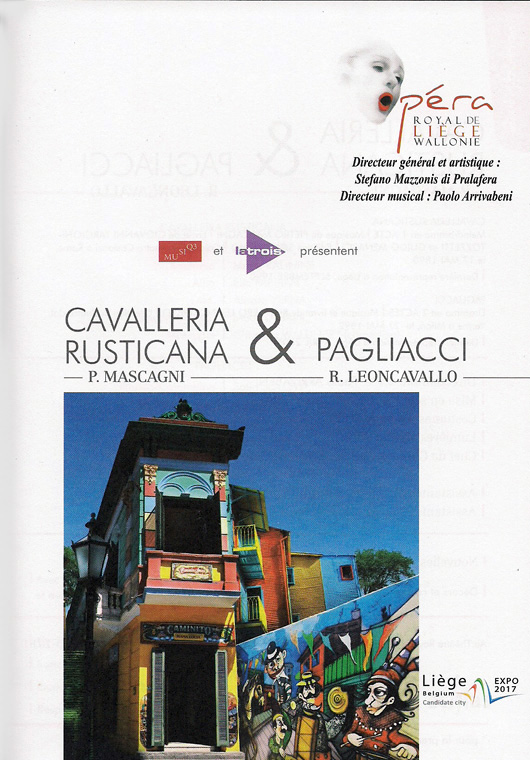

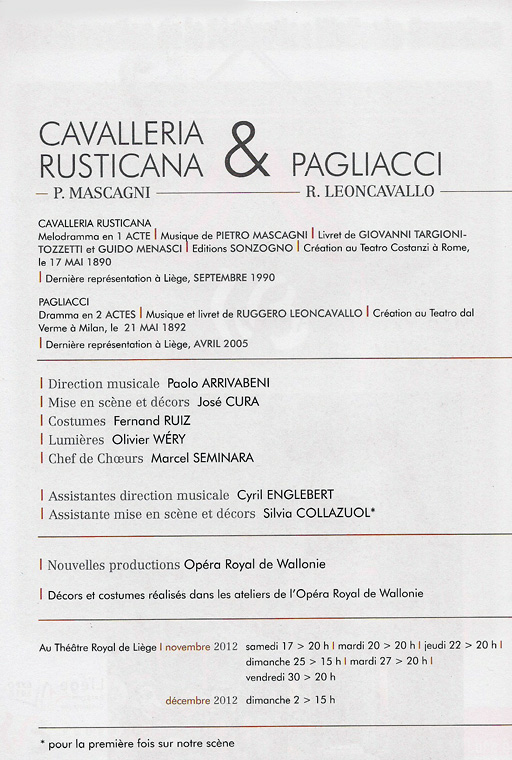

Though

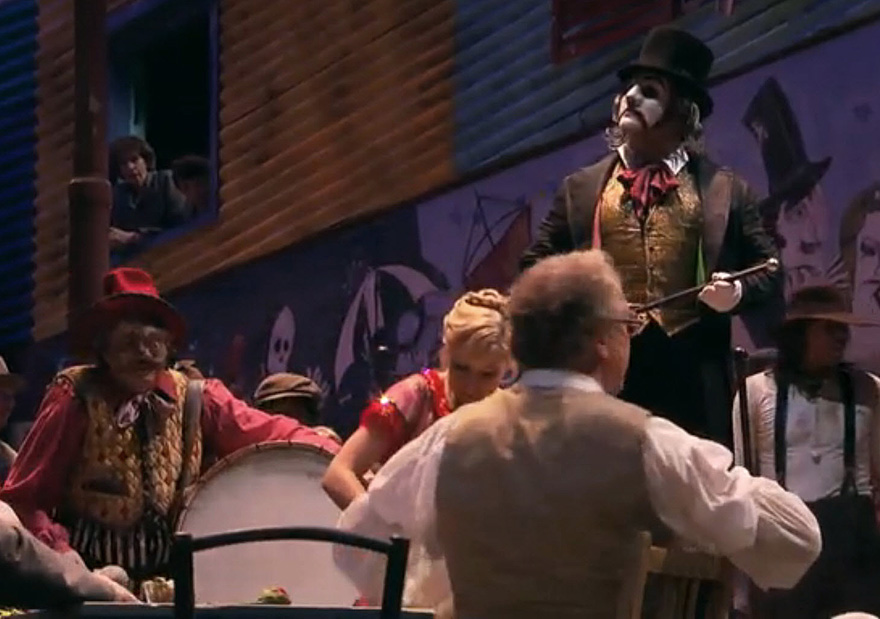

we begin with Cavalleria rusticana, Cura’s staging of

this independent opera becomes so intertwined with its companion

Pagliacci that it in fact becomes the first act of an

extended, integrated tragedy. Both operas take place in the

same location, innovatively reset to the Caminito in the La Boca

barrio of Buenos Aires, an area noted for its Italian heritage

but with the vibrancy of the new world; the setting allows Cura

to pay homage to his homeland in the use of vivid colors

(including those found in the Argentine flag) and the

incorporation of uniquely Argentine elements like the tango. The

splendid isolation of the Italian community clinging to homeland

traditions in the middle of a ‘foreign’ land underscores the

‘rustic gentleman’ solution of Cav and adds poignancy to the

love story between Silvio and Nedda.

Though

we begin with Cavalleria rusticana, Cura’s staging of

this independent opera becomes so intertwined with its companion

Pagliacci that it in fact becomes the first act of an

extended, integrated tragedy. Both operas take place in the

same location, innovatively reset to the Caminito in the La Boca

barrio of Buenos Aires, an area noted for its Italian heritage

but with the vibrancy of the new world; the setting allows Cura

to pay homage to his homeland in the use of vivid colors

(including those found in the Argentine flag) and the

incorporation of uniquely Argentine elements like the tango. The

splendid isolation of the Italian community clinging to homeland

traditions in the middle of a ‘foreign’ land underscores the

‘rustic gentleman’ solution of Cav and adds poignancy to the

love story between Silvio and Nedda.